If you listen to Steven Pinker, he’ll tell you the world has never been a better place:

Some graphs track increases in good things: income, longevity, sustenance, safety, literacy, democracy, civil rights, leisure and happiness. Others show declines in bad things: poverty, infant mortality, famine, state-sponsored torture, capital punishment, war, homicides, lynchings and racist attitudes. Together, the graphs demonstrate that we are wealthier, healthier, freer, more peaceful, smarter and nicer than we have ever been. Not by a little, but by a lot.

But if you open Zerohedge for just 20 seconds, you’ll not only find that the markets apparently will go to zero, even humanity. The battle between the optimists and the pessimists is a bit like the argument between cigar butt value investors and moving average quants. It’ll never end.

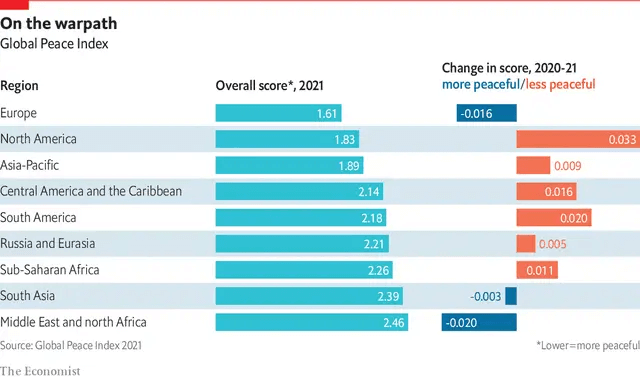

But, if you were to believe the liberal dishrag that is The Economist, certain parts of the world are getting worse by some measures:

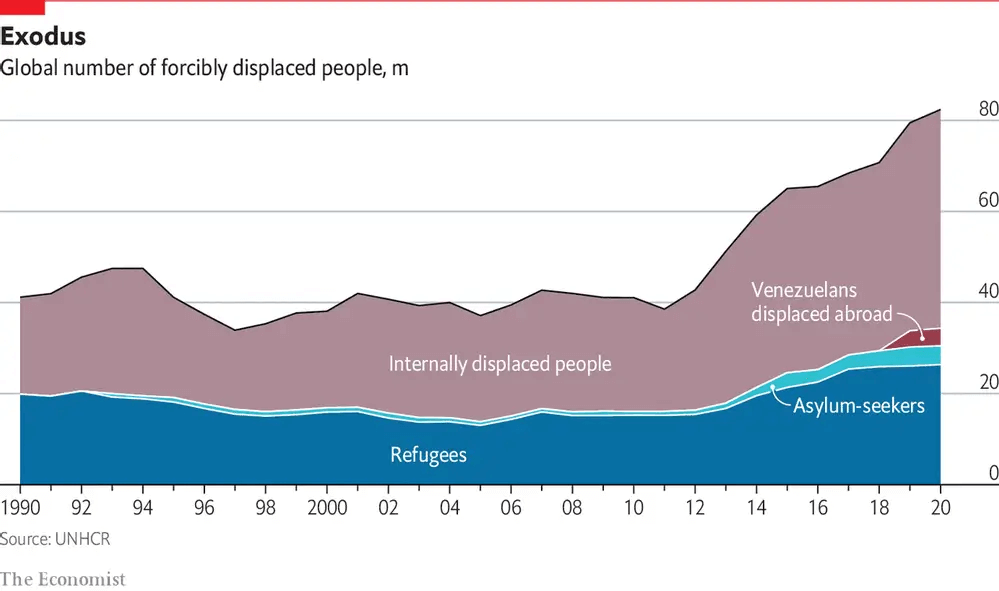

The number of people being displaced are at an all-time high:

People from just five countries account for about half of those displaced abroad (see chart). The biggest share have left Syria, where the civil war which began in 2011 has settled into a bloody stalemate. Almost 5m Venezuelans have escaped an economic crisis and political repression in their home country. Afghans subject to terrorism and insurgency, and South Sudanese caught in the middle of fighting have also fled their homes. In Myanmar, more than 1m people have escaped civil war and the genocide of the Rohingyas.

The other problem with such profound issues is the tyranny of the aggregates.

The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.

Josef Stalin.

I don’t mean to be insensitive, but such debates also show the power of framing and the power of narratives. The same set of facts can be spun to show things in an extremely positive or negative light. And of course, like research shows, negativity will always have positivity for breakfast.

But, If you veer more toward the negative side, then you’ll run the risk of being painted as a Cassandra. Like with Perma bears like Marc Faber, John Hussman, and Peter Schiff. They’ve been pointing to some perfectly logical data points to support their position, but they’ve been spectacularly wrong for decades.

On the other hand, the Perma bulls have used the posturing of the Perma bears to spin their bullish narratives. And two people can have wildly different views on being optimistic or pessimistic by looking at the exact same things.

And two people can have polar opposite views on being optimistic vs being pessimistic.

Here’s Morgan Housel:

Hearing that the world is going to hell is more interesting than forecasting that things will gradually get better over time, even if the latter is accurate for most people most of the time. Pessimism can be hard to distinguish from critical thinking and is often taken more seriously than optimism, which can be hard to distinguish from salesmanship and aloofness.

Morgan Housel

And here’s Adam Grant:

I suppose what I’m trying to say is that we’re all slaves to narratives. Being dispassionate and objective about something is pretty much almost impossible. And we’re always operating with just a slice of information and context, and we over extrapolate those things to suit our priors. And our conscious brain has just 512KB of memory. It’s nowhere near suited to large amounts of facts and forming opinions. Availability bias is strong among all of us, and we’re mostly acting based on salient information.

Of course, the easiest thing is to say that people should consider all the facts and make judgements, but that’s silly if you think about it. By the time it reaches us, most of what we know is usually lost in translation and slowly stripped of context.

This is why, in things like investing, unless you’ve reached a zen state of mind, investing based on beliefs and feelings can be dangerous. It might work for a few, but not for everyone. Of late, everyone touts systems and automation as a solution to these human foibles. But they aren’t a silver bullet either. Systems and automated processes reflect the biases of the maker.

Having said that, a set of robust processes rooted in evidence are almost always better than the human gut. Which begs the question, how do you form opinions in real life? I’m no Munger fanboy, but it does remind me of a quote of his:

I never allow myself to have an opinion on anything that. I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do.

Charlie Munger

This was a lot of meandering and going to many places without getting anywhere 😃 But hopefully, as I write more, I’ll be able to get to places a lot quicker than this piece. Apologies if you’ve read this piece and wanted to delete the internet.

Leave a Reply