One of the oldest clichés in finance is that retail investors are “dumb money” and institutional investors are “smart money.” There’s some truth to the cliché. Retail investors do all sorts of silly things. They are too optimistic, trade their pants off, take unnecessary risks, buy shiny objects, chase performance, form cults, cause market mispricing, and end up as the roadkill for informed investors.

But I got a problem with the stupid cliché for a few reasons:

- Saying all retail investors are stupid is as stupid as thinking veg biryani exists. It doesn’t, it’s pulav. As Terry Pratchett said: “The reason that clichés become clichés is that they are the hammers and screwdrivers in the toolbox of communication.”

- It’s true that retail investors do dumb things, but painting everyone with the same brush is unfair. In many cases, the so-called dumb money is much smarter than the so-called smart money. For example, a retail investor who invests in an index or even an active fund and sticks with it will outperform most institutions.

- It’s also unfair to institutional investors because the financial media doesn’t talk about all the dumb things they do.

At this point, the foul deeds of retail investors are the stuff of legend. Every day, hundreds of articles and videos find dull ways to regurgitate the same old things—blah, blah, dumb money is doing something dumb, blah, blah.

But is smart money smart?

No.

Institutional investors are also capable of dumb things. Imagine working at an institution where you work hard to do dumb things day in and day out, but the media ignores you. That’s not fair, right? So, let’s look at some dumb things institutional investors do.

Manager selection

The largest institutional investors manage money on behalf of others. Pension funds manage assets on behalf of their pensioners. Endowments and foundations manage the money of the organizations they belong to, such as universities, charities, and cultural institutions like museums.

To meet the liabilities, these institutional investors invest in various asset classes like equities, bonds, and alternatives like private equity, venture capital, real estate, and infrastructure. They may manage the money on their own or hire external fund managers like BlackRock (public markets), Blackstone (private equity), and Sequoia (venture capital).

Guess what the common metric for picking managers is?

The past 3-year performance.

No, I’m not kidding. I wish I were. But I am not.

For all the supposed smarts, past performance is the most common strategy institutional investors use to pick fund managers. It might shock you, but this strategy is stupid because performance tends to be mean reverting.

There’s plenty of evidence to show that managers chosen based on good past performance underperform in the future. Institutions also typically fire managers that underperform for three years. As counterintuitive as it sounds, these institutions would’ve been better off sticking with the managers. Better yet, Cornell et al. (2016), and Jeffrey Ptak, among others, show that hiring managers with poor past performance is a better strategy for picking managers than managers with good past performance.

Sad.

In 2008, Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal wrote a seminal paper on manager selection by institutions. They looked at the performance of managers pre- and post-firing. They also decomposed the returns based on the reason for the firing, such as performance, change in fund managers, and regulatory reasons. They found that performance was the key reason for hiring and firing managers. The irony was that institutions would’ve been better off doing nothing. Studies by Scott Stewart [1,2], Raul Leote de Carvalho, Howard Jones, and Jose Vicente Martinez showed the same.

Institutions also hire fancy consultants to pick managers, but consultants are just as bad as the institutions at picking managers.

Some smart money this is.

Any price for cold comfort

Humans will do anything to avoid pain and discomfort—from murder to paying 2 and 20 to avoid mark-to-market prices.

— Swami Bhuvan.

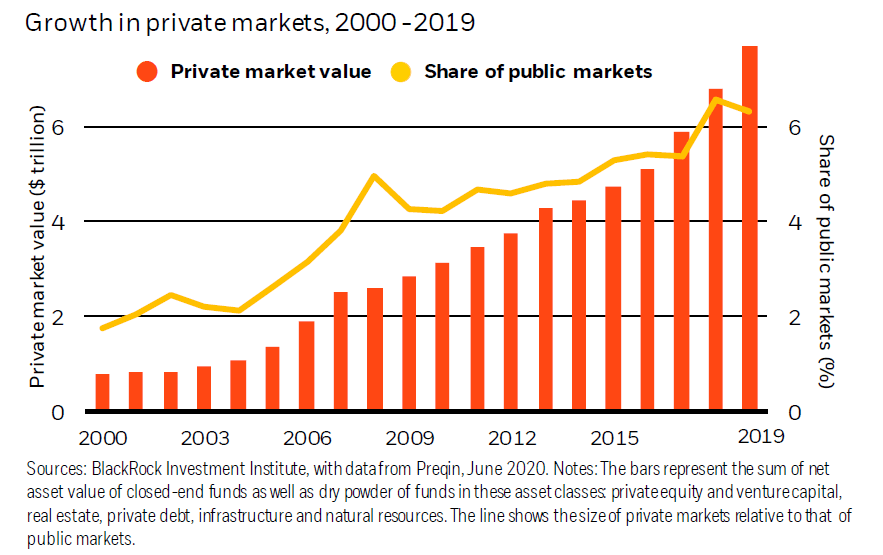

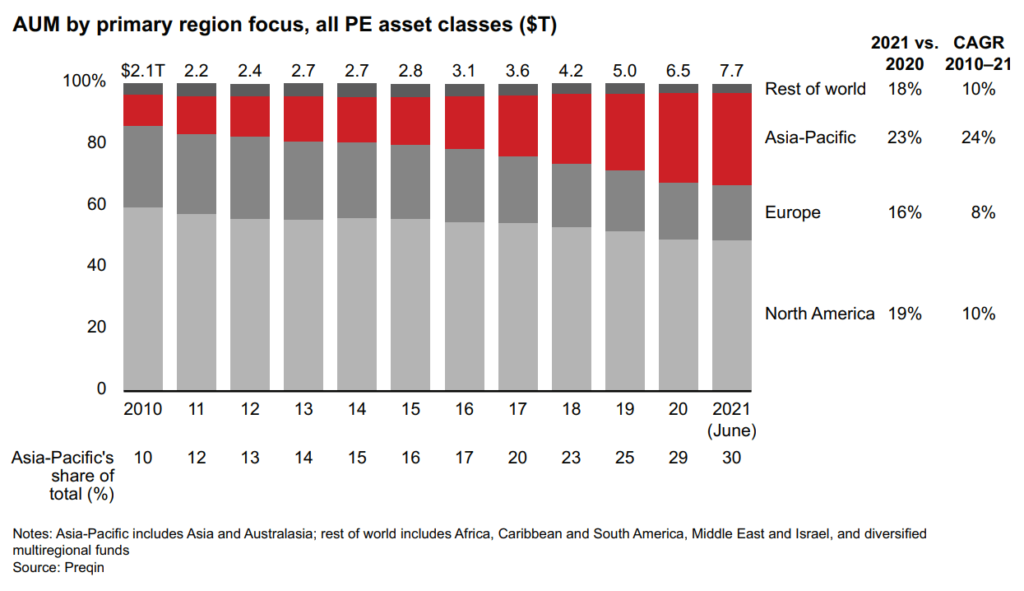

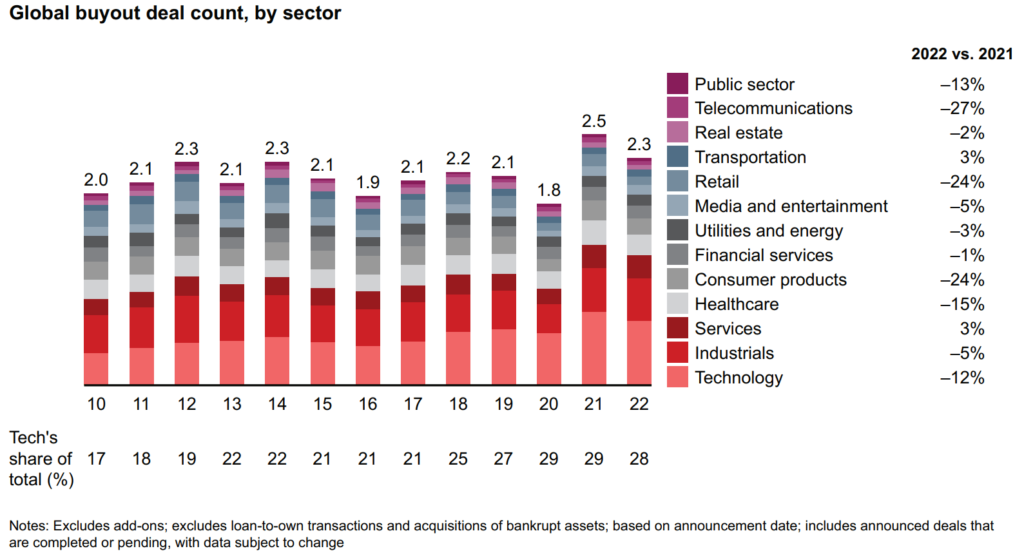

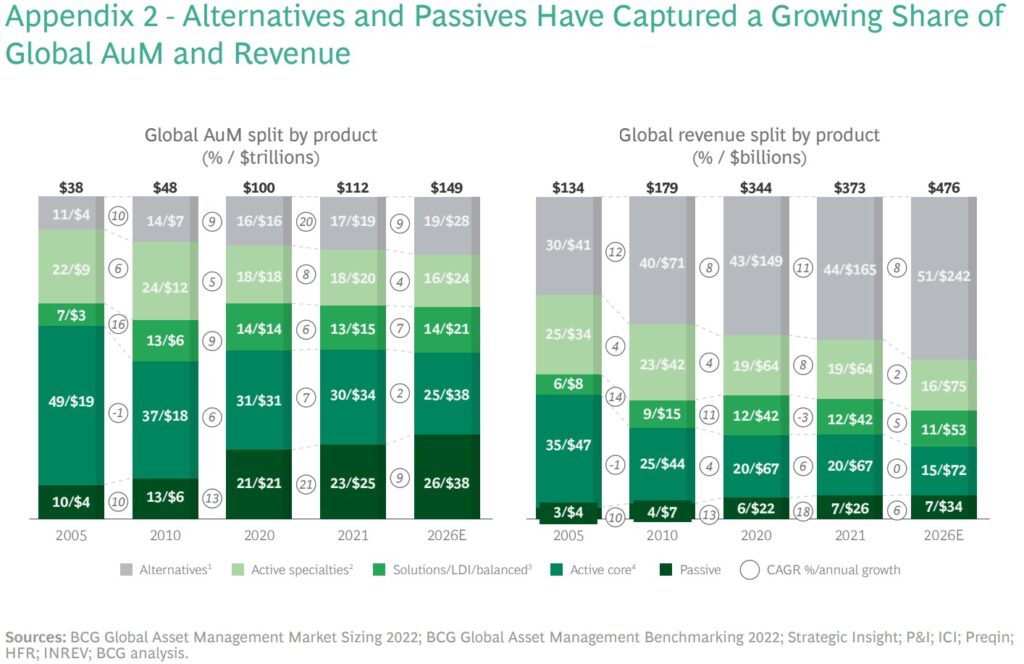

The rise of private markets has been one of the biggest trends in the financial markets over the last two decades. The United States and Europe account for most of the AUM, but Asia has grown faster.

Notes 1. PE and VC are also called "alternatives." 2. Private markets is a catch-all term for private equity (PE), real estate (RE), venture capital (VC), private debt, infrastructure, and natural resources. 3. Some refer to all these things as "private equity," while others define private equity as only "leveraged buyouts." In this post, I'm using the all-encompassing definition.

People attribute the growth of private markets to the low-interest rate environment, easy liquidity, and the hunt-for-yield phenomenon. These factors played a role, but there were more tailwinds.

What were the factors that led to the rise of the private markets?

- Pensions and insurers have long-term liabilities, and they need to hit specific return targets to meet those liabilities. If interest rates and, by extension, bond yields are low, it becomes harder to meet those liabilities. Declining yields and lower expected returns force them to take more risks.

- Pensions across the world are underfunded. These shortfalls force them to seek additional returns to bridge the return gap.

- Growth of large institutional pools of capital like sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and family offices in the last three-odd decades. These entities have become major players in financial markets.

- Changing market structure and the decline in the number of publicly listed companies and IPOs worldwide.

- Changing regulations and the growing cost of public markets compliance.

- Good old herding. Institutional investors aren’t immune to fads and performance chasing. The monkey see, monkey do phenomenon is prevalent not just among retail investors.

- The regulatory changes post-2008 led to banks retrenching from a lot of areas. Players like private credit and fintechs have stepped in to fill the gap.

So what does this all mean?

One way of looking at this is how these factors change the way institutions invest. Based on certain return assumptions, analysts at Callan looked at what it would take to earn a 7% nominal return (5% real return).

The graphic below shows that the pattern of increasing complexity over time remains similar over the 30-year period, although the level of additional risk is lower. Today investors need to take on roughly 2½ times the volatility as they did 30 years ago to earn a 5% real expected return, versus over 5 times the risk when matching nominal return expectations.

Things have become even trickier since the piece was published, with inflation at 7-8%.

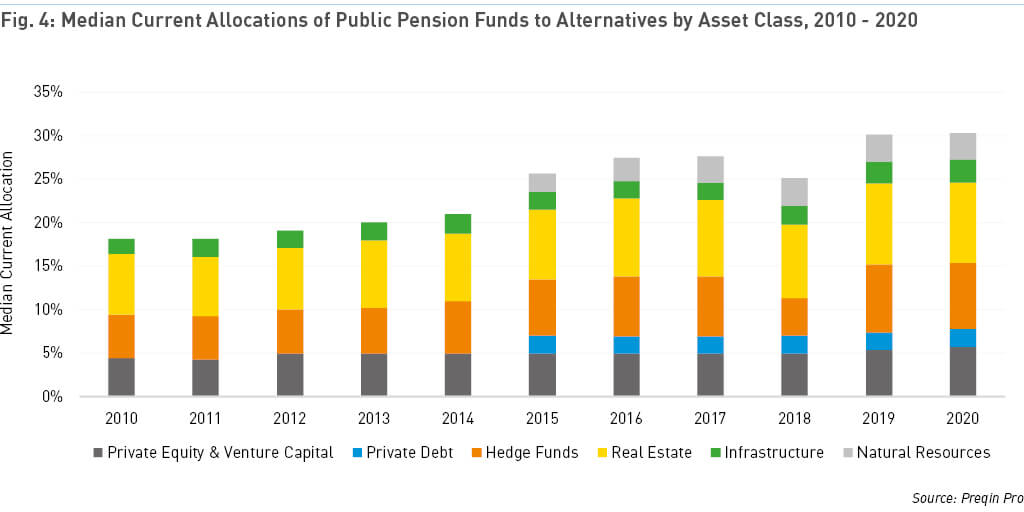

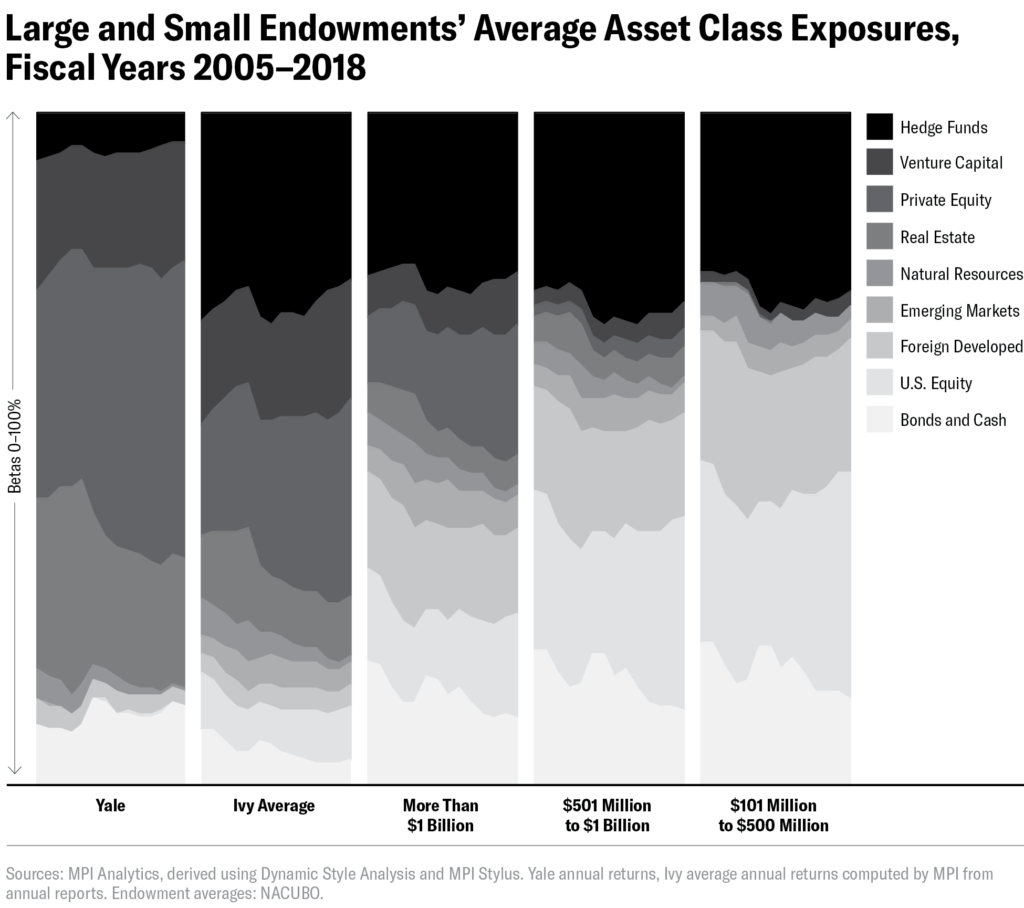

All these factors have led to institutional investors increasing their allocation to private equity, venture capital, real estate, and other alternative investments. On average, the allocation to private markets by institutional investors ranges from 10%-50% across the developed world.

This shift from equities and bonds to a mix of other private assets is called the endowment model. David Swensen pioneered it at Yale and inspired a generation of allocators who’ve tried to emulate him, with mixed results.

Falling interest rates and the other structural issues I mentioned above have pushed pensions to increase allocations to private markets. If you still think this is a small allocation, consider that pension funds in the 22 largest countries manage over $56 trillion in assets. When you include other large investors in private markets, such as sovereign wealth funds, endowments, asset managers, and insurance companies, the number goes up to $175 trillion. Even a 1% allocation moves billions.

On average, pension funds in developed markets increased their allocations to alternatives from 7.22% of assets under management (AUM) in 2008 to 11.76% in 2017, a 63% increase. The top ten countries with the largest allocations to Alts as of 2017 were Italy (21.4%), the United States (19.6% of AUM), Canada (17.4%), South Korea (15.9%), Switzerland (14.4%), Brazil (13.8%), Germany (9.1%), Sweden (6.9%), the United Kingdom (4.9%) and Finland (3.5%).

When the Tailwind Stops: The Private Equity Industry in the New Interest Rate Environment – CEPR

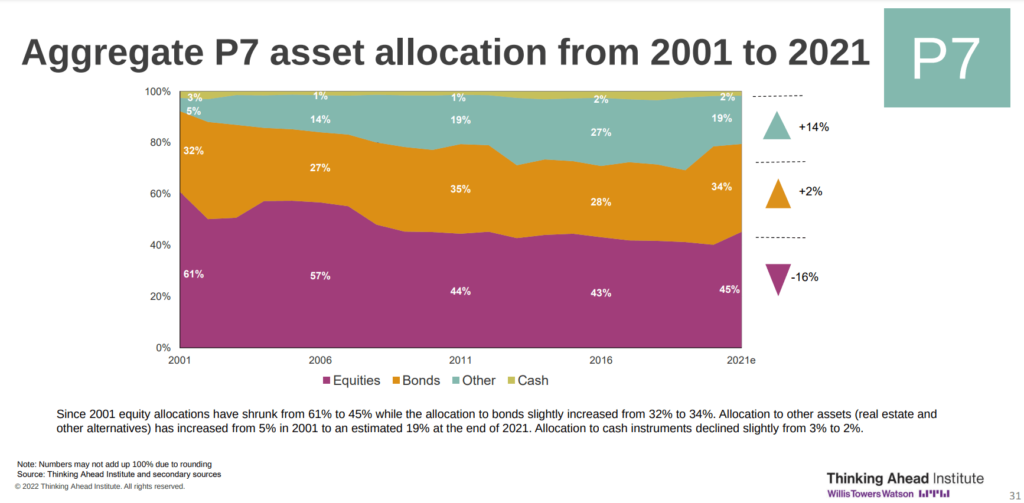

Pension fund asset allocation in the 7 largest pension markets—Australia, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the UK, and the US.

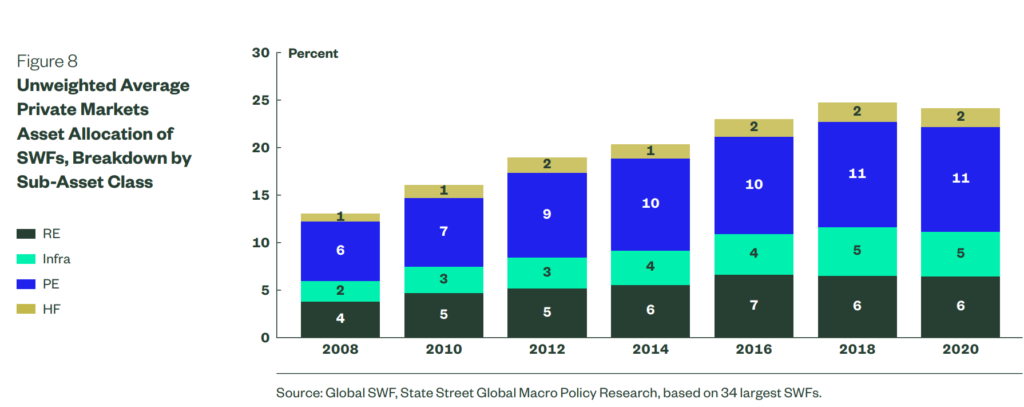

It’s not just pensions and endowments; even sovereign wealth funds have dived head-first into private markets.

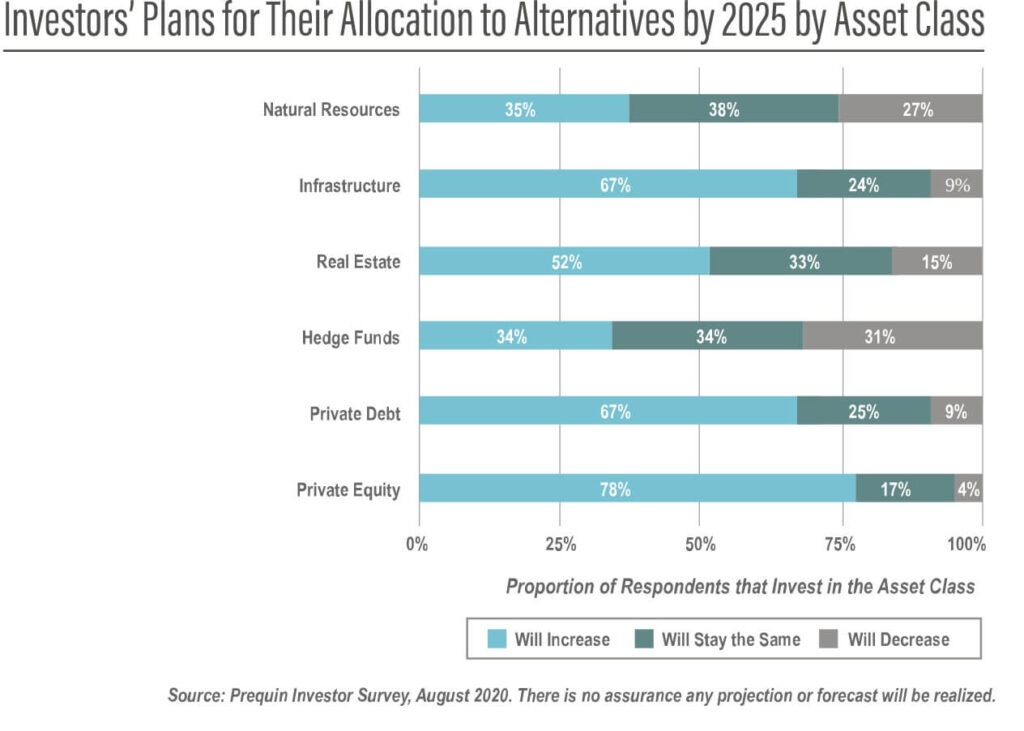

The rush to private markets is only getting started.

What explains the dramatic shift into private markets? The common reasons touted by allocators are:

- Private markets outperform public markets with half the volatility.

- They offer better diversification compared to traditional stocks and bonds.

- They offer access to better opportunities since companies are staying private for longer.

- Private investors can create more value because they have a much longer investment horizon than public market investors.

Is private equity a fairy tale? Before we jump to conclusions, let’s unpack this.

The views about private equity fall on a broad spectrum. On one end of the spectrum, you have Elizabeth Warren, who likened private equity to vampires. Then you have Jeff Hooke, professor of finance at Johns Hopkins and author of The Myth of Private Equity, who says that believing in private equity outperformance is like believing in the tooth fairy. Ludovic Phalippou, the author of Private Equity Laid Bare and professor of financial economics at the University of Oxford, calls private equity a billionaire factory. On the other end, you have people like Steve Kaplan and Steven Davis, both professors at the Chicago Booth School, who think private equity is a force for good.

If you’re a public markets investor, you wouldn’t think much about performance measurement because you have real-time pricing and easy access to historical data. You’d think this shouldn’t be an issue for a $10 trillion asset class like private markets, but you’d be wrong. Something as basic as performance measurement is a nightmare. If you ask five people about the performance of private equity, you will get ten answers.

Why the disconnect?

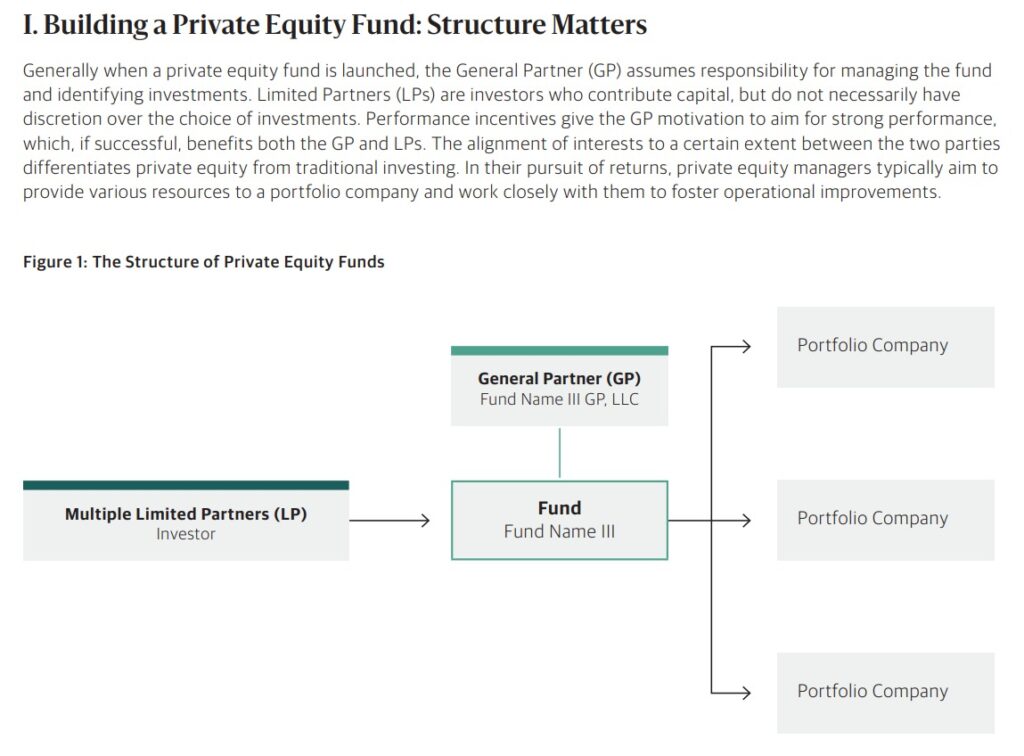

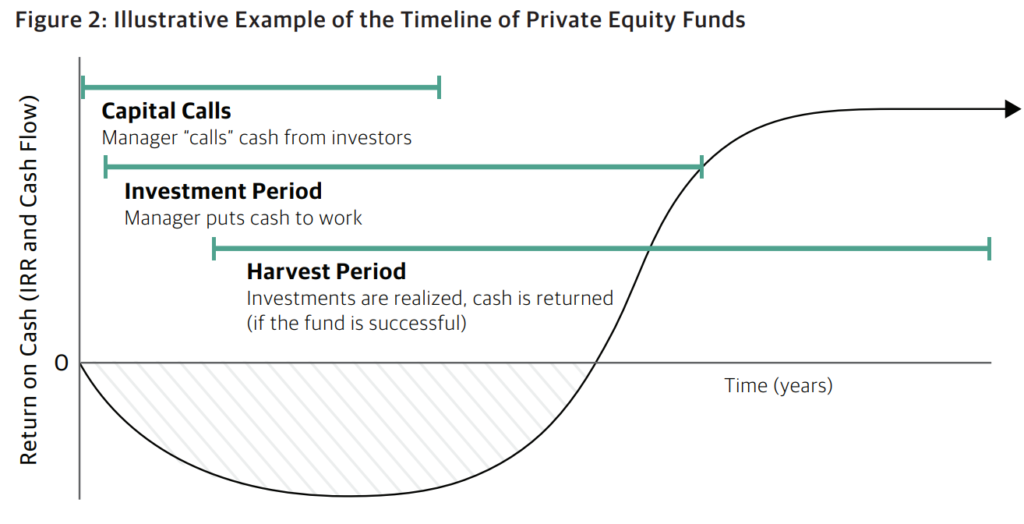

As a refresher, a private equity fund is like a closed-end fund. Private equity firms say they can acquire existing companies and improve their performance.

Structure of a private equity fund.

Fund

Private equity companies like Blackstone or KKR create funds that target a specific sector like healthcare, technology, energy, etc. The common fund structure is a limited liability partnership (LLP). The typical life of a private equity fund is 10 years, but it can be extended for a couple of years.

Investors

The fund then raises money from investors such as pension funds, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds. The investors in a fund are called limited partners (LP).

Management

Much like a mutual fund, a private equity fund will have a manager(s) whose job is to identify companies, acquire them, improve them, and sell them. The fund manager in a PE fund is called a general partner (GP). Unlike a mutual fund, all the money isn’t invested right at the start. LPs commit money to the fund, but the GP calls for the money as and when he identifies opportunities. The GP invests the capital in the first 5 years and then starts selling the companies after, returning the money to the LPs after fees. The sales can be through IPOs, secondary sales to other companies, or private equity firms.

Fees

A private equity fund typically charges a management fee of 1.5%-2% and a performance fee or carry (carried interest) of 20%.

Performance reporting

Most PE funds disclose their NAVs every quarter. Mutual funds invest in publicly traded securities like stocks and bonds that, for the most part, have real-time pricing. So measuring the performance of a mutual fund is easy. But a private equity fund holds private securities that don’t trade. So, private equity firms use fair value or appraisal accounting methods to value the companies they own. It’s a hypothetical price at which you can sell a company. Private equity firms have to adhere to guidelines, such as the fair value guidelines from the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), but despite that, the valuation is based on the opinion of the fund manager (GP).

As you can imagine, this leads to all sorts of issues. Nobody cared about this when the private markets were small. But with over $10 trillion in AUM globally, the private markets are no longer a cottage industry. Private equity manages trillions that belong to public pensions and sovereign wealth funds, which taxpayers and public workers like Govt teachers, firemen, and municipal workers fund. Knowing whether the fiduciaries managing these public pools of money are doing a good job is the least you should expect. After all, private markets are a notoriously costly asset class.

Discussions about private equity lead to questions about performance, fees, whether they create value, systemic risks, and their societal impact. In this post, my objective is to see how smart, professional institutional investors are. So let’s look at the performance of private equity first.

Whether private markets outperform public markets has to be among the loudest debates in modern finance. Nobody agrees on anything because of the opaque nature of the asset class and the lack of accurate data. Publicly traded securities have time series data based on actual trades. This makes it easy to use models like CAPM and the Fama-French factor models to analyze risk and return characteristics.

But private equity funds don’t have market values because the underlying companies are private. Even though private equity funds disclose their net asset values (NAV), the valuations of the underlying companies are based on the opinions of the fund manager. The NAVs are published every quarter, but they tend to be stale. There’s widespread evidence that private equity funds manipulate returns and valuations. Funds are also secretive about the returns. In 2003, Sequoia terminated its relationship with the University of Michigan after the endowment was forced to disclose the returns of its private market investments.

Researchers and academics use databases maintained by firms like Prequin, Burgiss, and Cambridge Associates to analyze private data, but they suffer from obvious self-selection and self-reporting issues. To give you a sense of how difficult it is to get PE data, Prequin collects its data through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to public pensions in the US and UK. To make matters worse, the fund cash flows are also irregular, and the valuations of company exits can only be determined after the exit. We’re only talking about measuring returns.

So how has private equity performed?

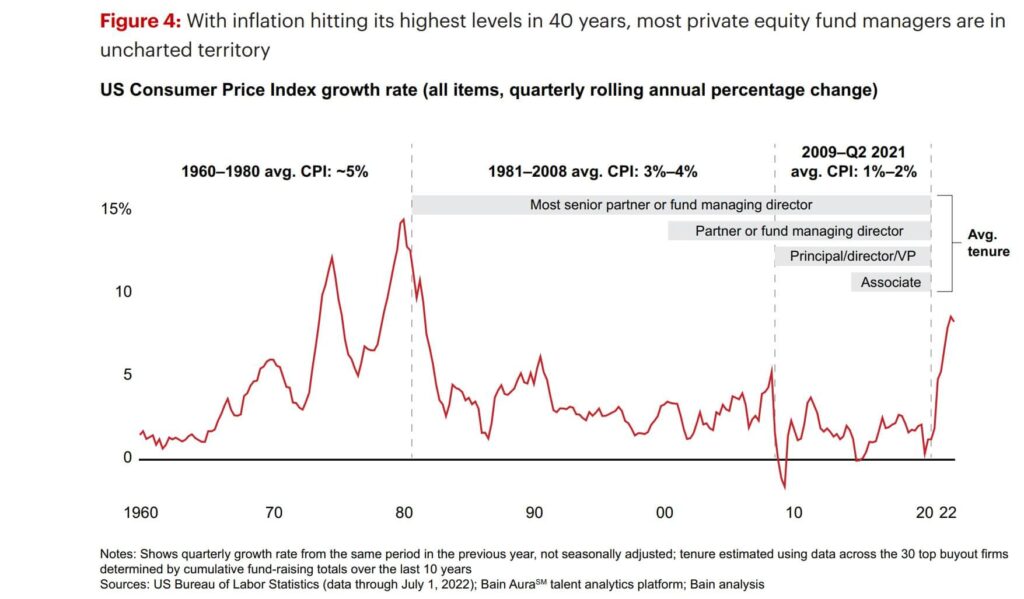

Private equity became mainstream only in the 1980s. If you remove the first 5 years and the last 5 years because that’s usually the fund formation and termination stage, the industry is only 30 years old. If you only consider the period where the assets start increasing, that would further reduce the time period to just about 20+ years. The industry hasn’t even seen a proper inflationary economic cycle.

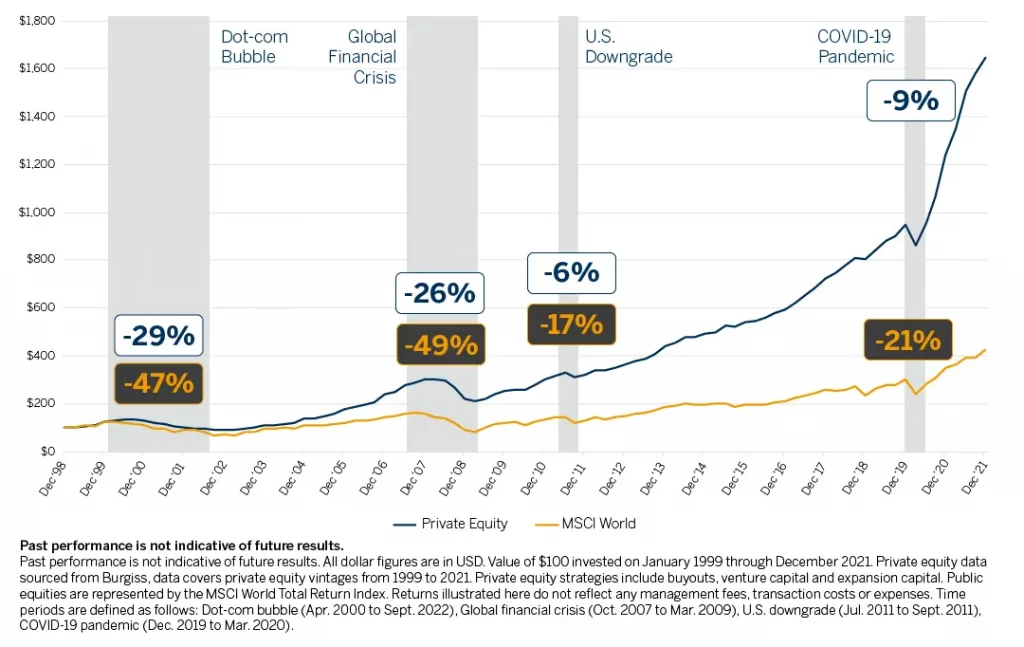

But anyway, this is the typical image you see when people talk about private equity, especially those from the industry. The common view is that high PE returns are a compensation for holding an illiquid asset in which you’re locked in for 10 years.

3X the returns with half the volatility of the public markets. What more do you want in life?

But. Yes, there’s always a but.

The only instrument in which you can get twice the public market returns with half the volatility is a Ponzi scheme.

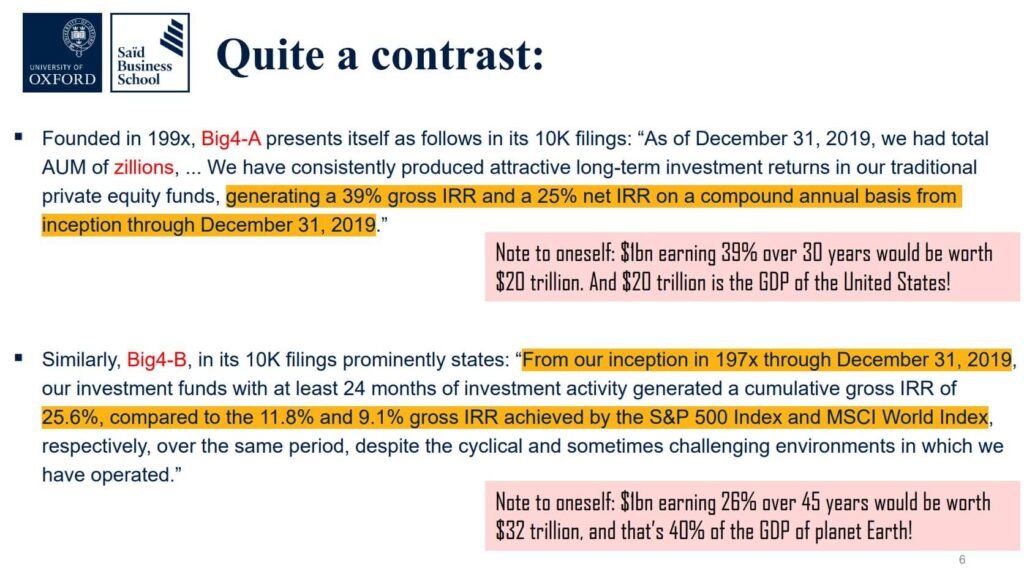

The popular metric used to measure private equity performance is the internal rate of return (IRR). But as Howard Marks said in his famous memo titled “you can’t eat IRR,” it’s a flawed measure because it assumes that the capital paid out will be reinvested at the same rate. There are numerous ways in which IRR can be further manipulated through subscription lines (borrowing), dividend recaps, or timing of the sales of underlying companies. To overcome the issues with IRR, people use modified IRR (MIRR) is used. MIRR assumed the reinvestment at a more realistic rate of return, such as a public benchmark.

One of the best descriptions of the absurdity of using IRR was from a presentation used by Ludovic Pahlippou, one of the loudest critics of PE.

Founded in 199x, Big4-A presents itself as follows in its 10K filings: “As of December 31, 2019, we had total AUM of zillions, … We have consistently produced attractive long-term investment returns in our traditional private equity funds, generating a 39% gross IRR and a 25% net IRR on a compound annual basis from inception through December 31, 2019.

Ludovic Pahlippou

Note to oneself: $1bn earning 39% over 30 years would be worth $20 trillion. And $20 trillion is the GDP of the United States!

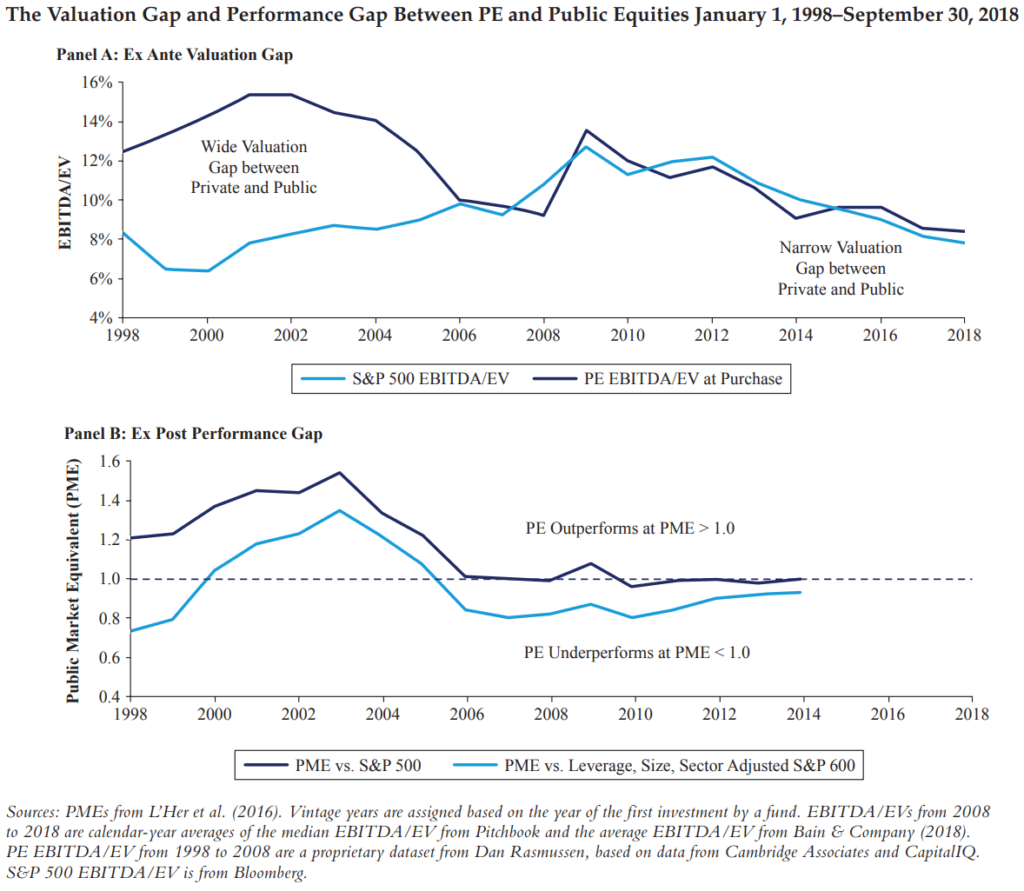

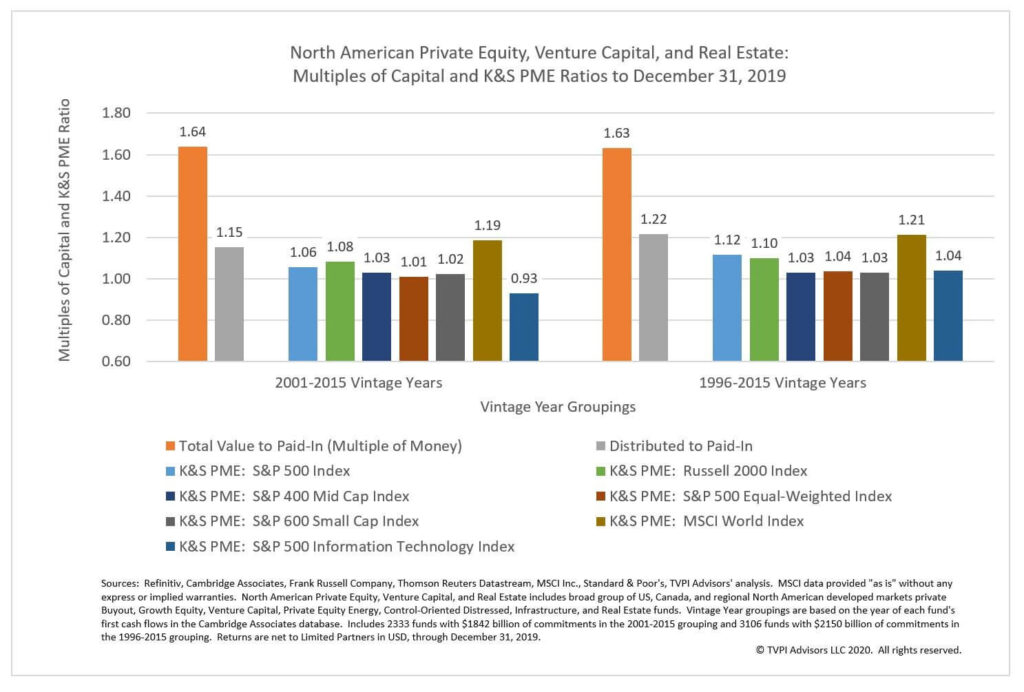

The other popular measure is money multiple, or total value to paid-in capital (TVPI). It measures the multiple of capital paid out to the capital paid in. But this measure doesn’t consider the time taken for the cash to be paid out. The public market equivalent (PME) is another alternative; it measures the performance of an equivalent investment in a public market like the S&P 500. Even though PME has its shortcomings, it’s a much more reasonable measure of PE performance compared to all the other metrics. One of the biggest issues with PME is the selection of the wrong benchmarks to make PE performance look good, like in the image above, but we’ll get to that later.

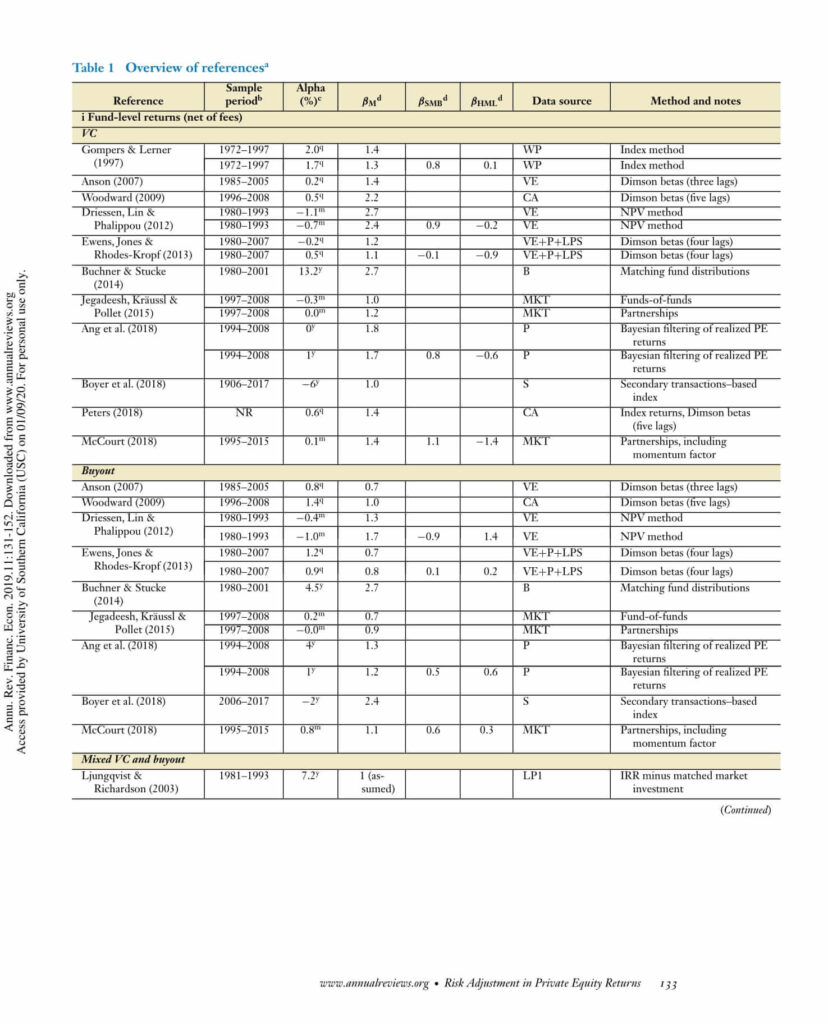

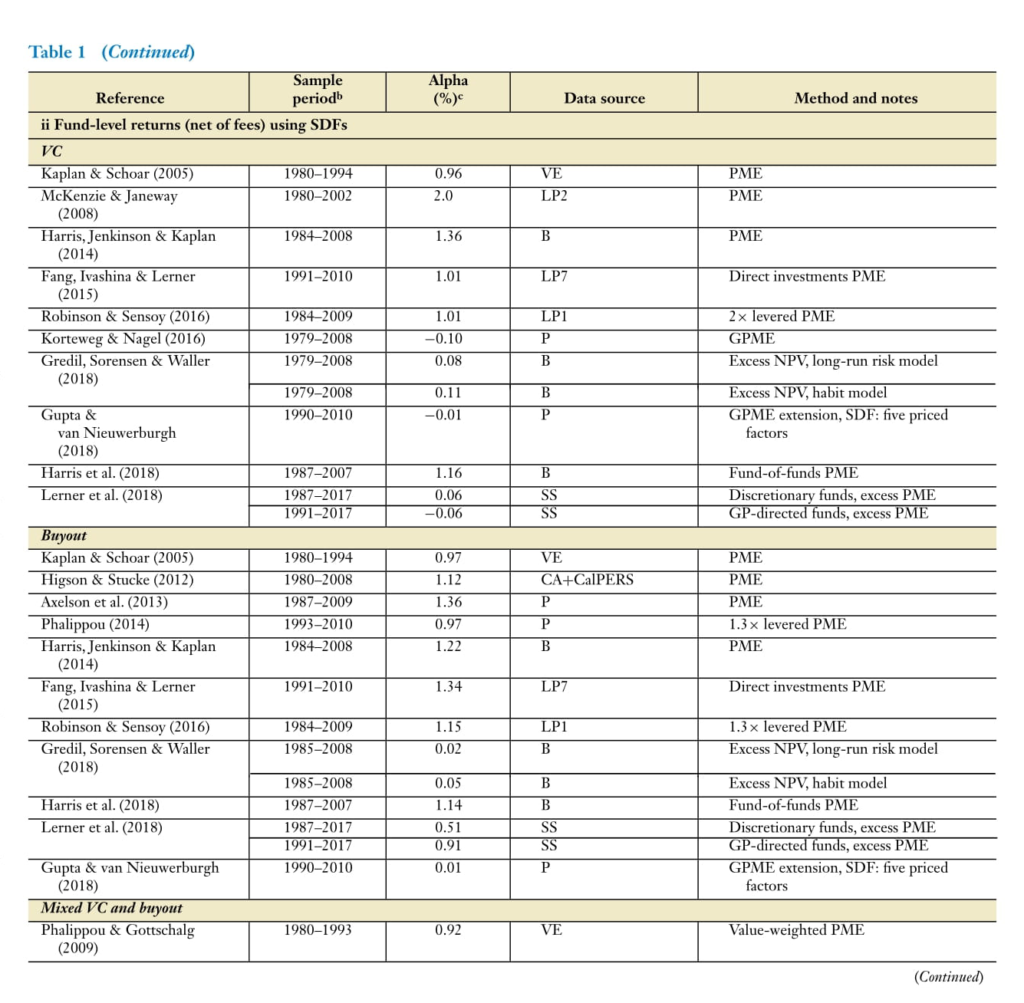

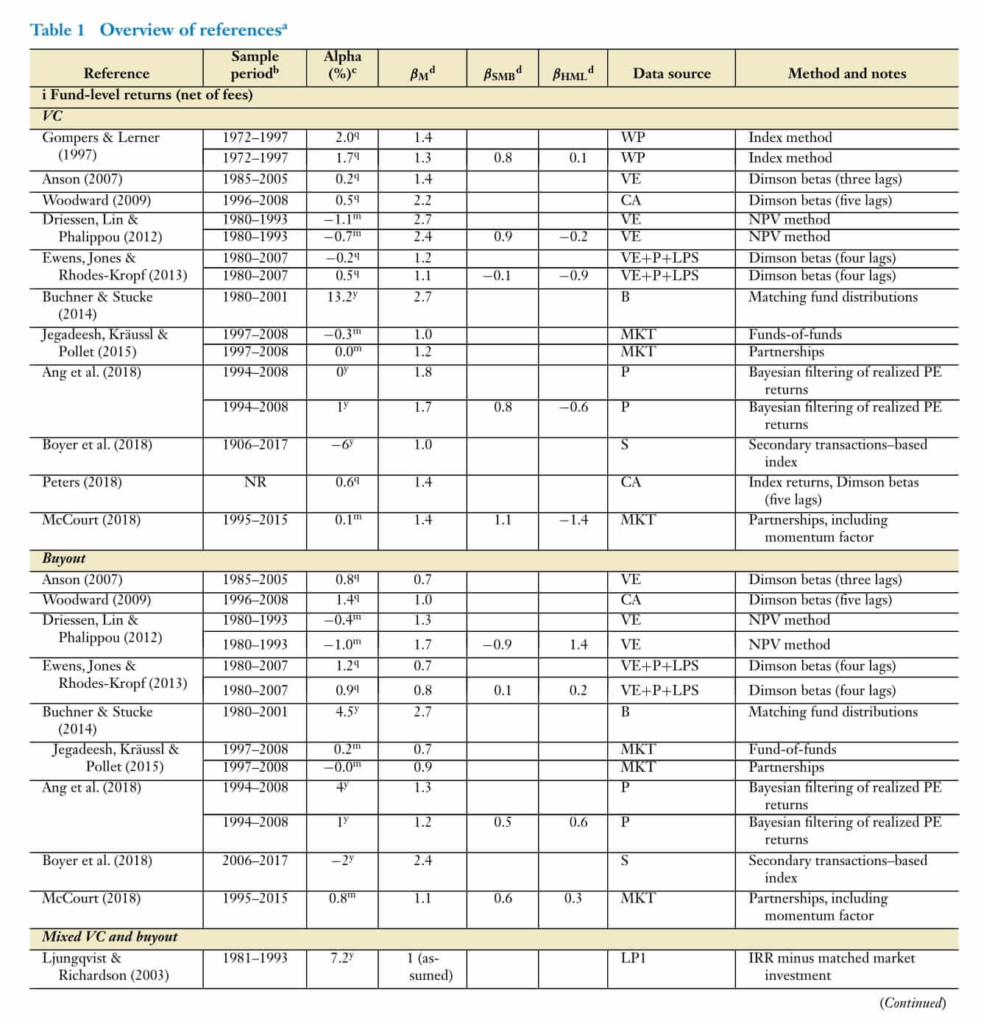

The results of studies analyzing the performance of private markets are all over the place. Here are a few snapshots from this excellent literature review by Arthur Kortweg. The studies are categorized by leveraged buyouts, venture capital, and mixed analyses. This goes back to the definition of private equity. For some, private equity means buyouts; for others, it’s an umbrella term for PE, VC, real assets, and infrastructure.

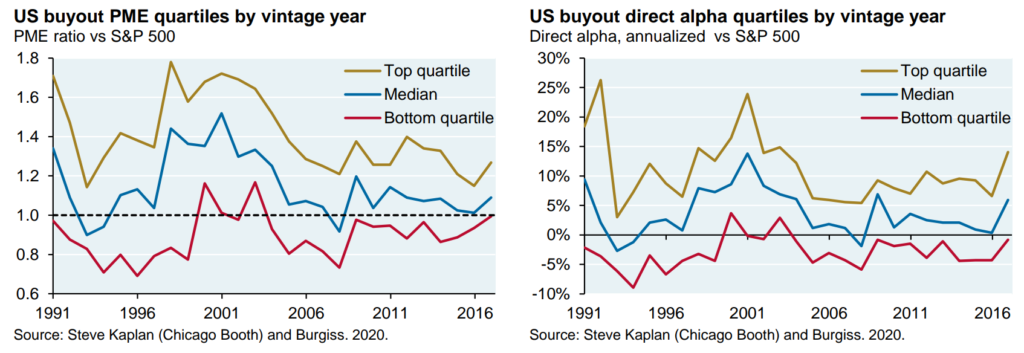

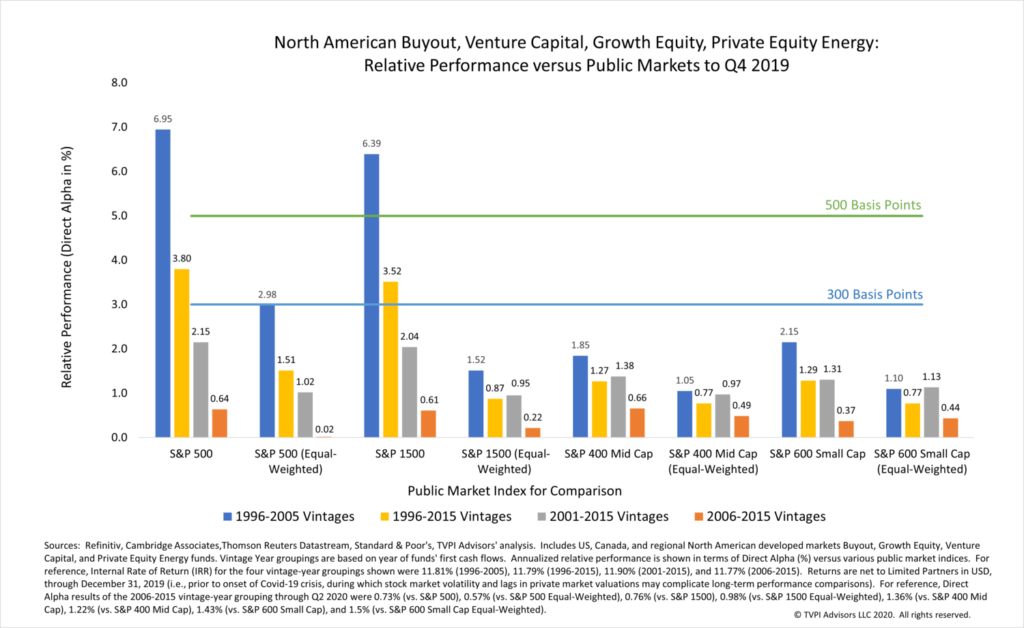

Steve Kaplan, Antoinette Schoar, David Robinson, Arthur Kortweg, Greg Brown, among others, believe private equity outperformed public markets. The alpha estimates range from 0.01% to 9.3%, and the market beta estimates range from 0.7 to 2.8. But others like Ludovic Phalippou, Jeff Hooke, Richard Ennis, Antti Ilmanen, and Narasimhan Jegadeesh disagree.

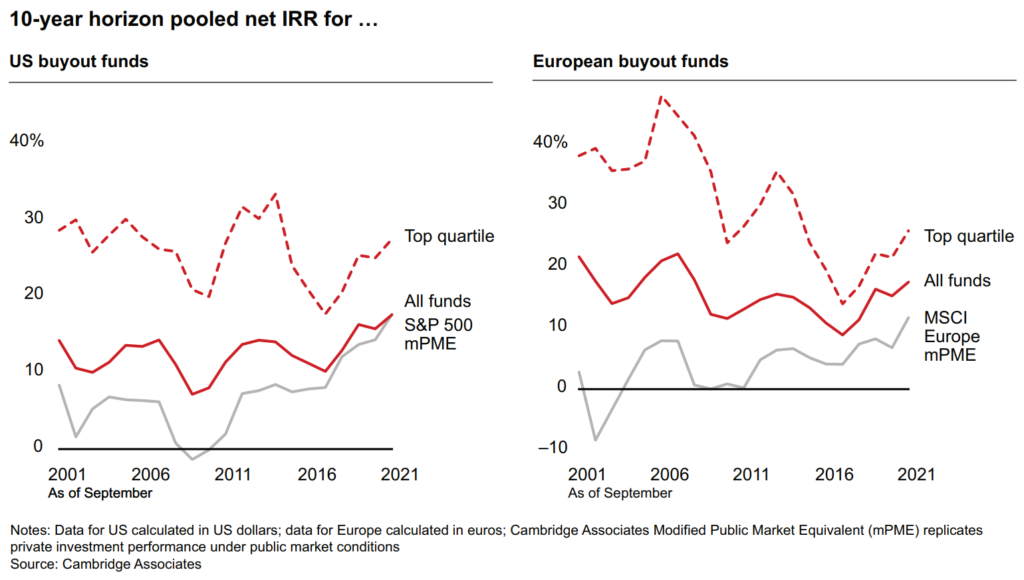

But there’s broad agreement that private equity returns since the 2008 crisis have been declining. This is visible even when using a flawed measure like IRR and when compared with the wrong benchmark like the S&P 500.

The disagreement on private equity performance is in part due to data sources, methodological differences in terms of risk adjustments, leverage adjustments, pre-fee calculations, and the choice of benchmarks. But some clever studies have tried to untangle these issues in interesting ways.

Let’s look at the issue of benchmarks first.

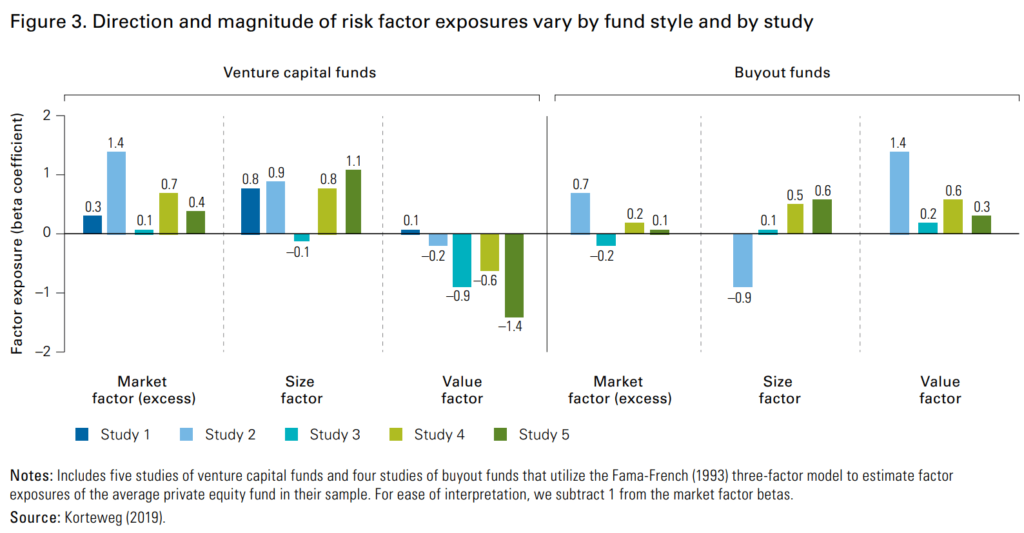

Most studies use the S&P 500 as the benchmark, but private equity investments are akin to small-cap companies. There’s a growing body of literature [1,2,3,4,5,6] that shows that private equity is just a leveraged small-cap investment. A study by Dan Rasmussen showed that you can replicate private equity returns with a basket of small-cap stocks mirroring the characteristics of those acquired by private equity firms. Another study by Erik Stafford showed that you can replicate private equity by levering up small and micro-caps with leverage from your brokerage account.

Studies that have tried to decompose the factor loadings of private equity have shown that private equity tends to have higher loadings toward size and value factors.

Ilmanen et al., 2019 tackle this issue of benchmark selection by comparing private equity returns against the Russell 2000 small-cap index by levering it by 1.2X. When compared against this levered small-cap, the outperformance of PE all but vanishes. It’s the same when you compare PE to the S&P 600 small-cap index adjusted for leverage and sector exposure.

Eric Johnson, the creator of the Modified Public Market Equivalent (mPME) methodology, published a comprehensive study of PE performance. His conclusions were similar, that the outperformance of private equity all but vanishes when compared to mid-cap, small-cap, and equal-weighted indices. You could argue that combining buyout, venture, and real estate is wrong. But Ilmanen et al. (2019) show that unlisted real estate has underperformed listed REITs. As for venture capital, if you remove the dot-com bubble period, the performance is similar to Nasdaq Composite.

On an interesting note, Tiger Global partner Scott Shleifer in a recent conference, had this to say about their venture capital returns in India:

“Returns on capital in India have sucked historically. If you look at the market-leading internet companies, whether it is Google, Facebook, Alibaba or Tencent, revenue for them got bigger than cost more than a decade ago. You had a great legacy of last 17-18 years of materially profitable internet companies. So returns on equity in the internet got really high and the returns for investors have been really high. But that did not happen in India,”

It seems to me that the reason for the public markets vs. private markets is that people look at them from a public market lens. The private equity guys will have you believe that’s wrong and that they’re special. But what happens if you extend the same line of thinking?

A few studies take some interesting approaches to compare the performance of private equity to public markets.

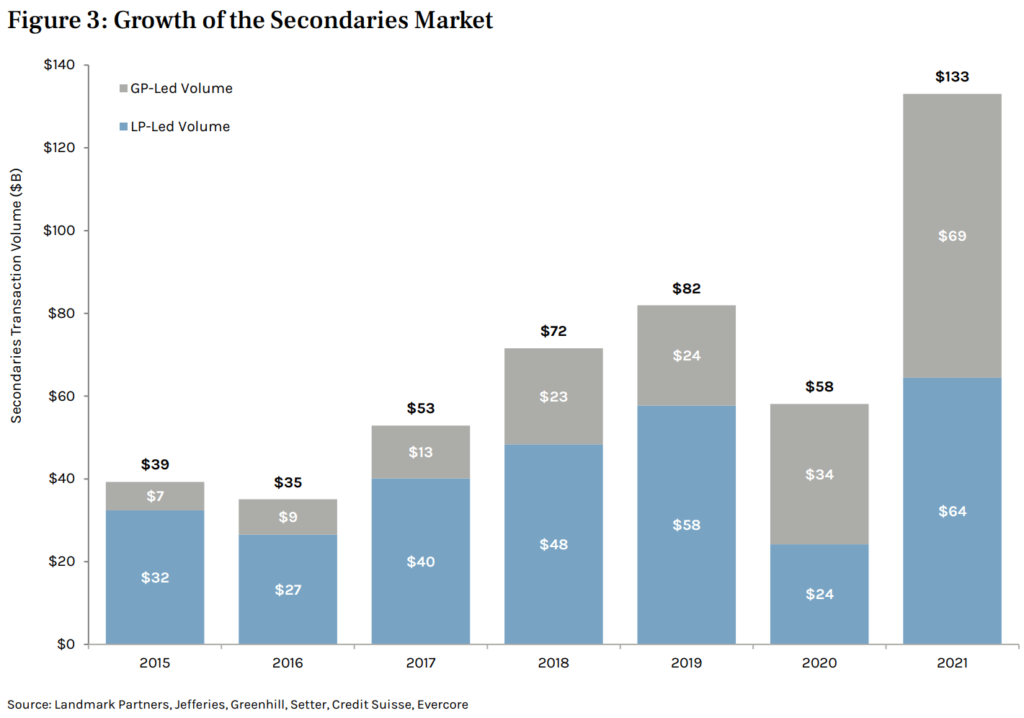

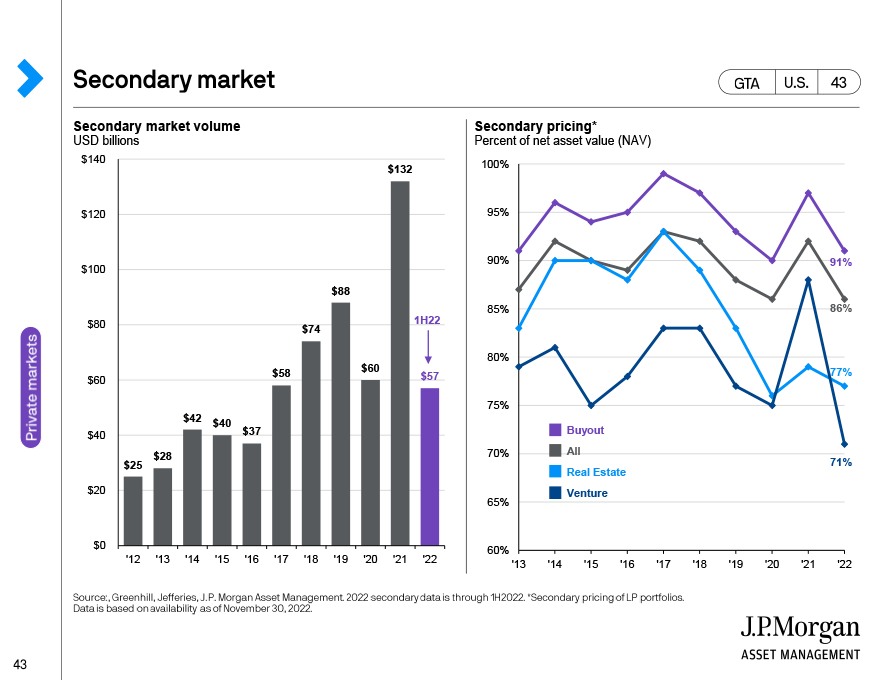

Unlike public markets, private markets don’t have a deep and liquid secondary market. Though the secondary market for private equity grew to $130+ billion in 2021, it’s still tiny compared to the AUM.

To get around the issues with private equity data, Boyer et al. (2019) used secondary deals data to build private equity indices. They find that private equity is much riskier than public equities, with a beta of over 2 and negative alpha in contrast to indices based on NAVs.

This matches the recent evidence from secondary sales, even though LPs have been reluctant to mark down their portfolios.

Jegadeesh et al. (2009) analyzed listed fund of funds (FOFs) and listed private equity companies (LPE) that invest in private equity. They found that private equity FOFs and LPEs have negative alpha, beta close to one, and positive factor loading towards small and value factors.

Arpit Gupta and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh took a novel approach to analyze private equity. They strip the cash flows of private equity funds and match the horizon with corresponding strips for public securities like dividend strips, capital gain strips, and bond strips. The intuition is that the risk and returns of private equity funds can be matched to corresponding strips on publicly traded securities to tease out the similarities. They find that growth stocks are proxies for venture capital, REITs for real estate, and small, value, and growth stocks can be proxies for buyouts at various stages of the fund. They also find that when you adjust for risk, private equity has a negative alpha compared to replicated public portfolios.

What about the illiquidity premium?

Assume that you have a choice between investing in two stocks. Icky Ltd. is a stock with deep liquidity that you can sell anytime. Gooey Ltd. is not so liquid and doesn’t trade on most days. All things being equal, which of these two stocks should have higher expected returns? Gooey Ltd. is illiquid, so there should be compensation for it.

This is one of the selling points of private equity. Since you cannot enter and exit private equity whenever you want, like public equities, there’s an “illiquidity premium” for private equity investments.

But think about it for a second.

If private equity is just levered small or mid-cap equities, as we’ve seen so far, why would someone still invest in private equity? A few reasons come to mind:

- Private equity managers have discovered secret deposits of alpha that public equity managers haven’t.

- Private equity provides diversification benefits.

- Public markets are a giant distraction for institutional investors. If a pension fund is investing for 30–50 years, what’s the need for real-time pricing? Real-time pricing increases the chances of people making mistakes.

The evidence of private equity alpha is mixed. As for diversification, if all or most of the private equity returns can be explained by public market factors, then there’s no diversification benefit.

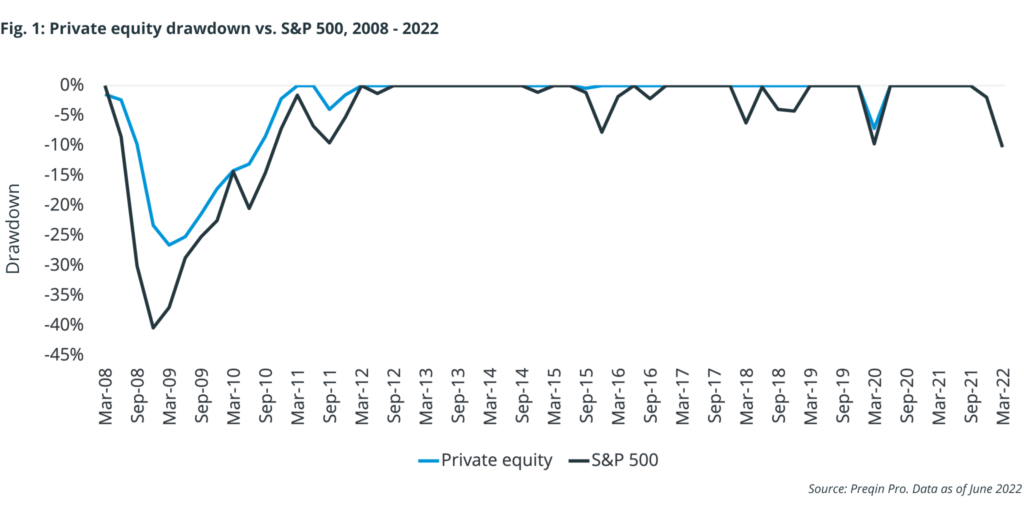

Yet private equity funds represent equity positions in corporates. Hence this low volatility must be artificial, the product of smoothed valuations. Private equity portfolio companies are influenced by the economic tides just as much as public companies, even if they don’t want this reflected in their valuations.

Nicolas Rabener

What if private equity is attractive because of its illiquidity? What if investors know that private equity is levered public equity, but they’d prefer not to wake up in the morning to see their portfolio down by 30%? What if there was a way to get public equity returns without real-time prices?

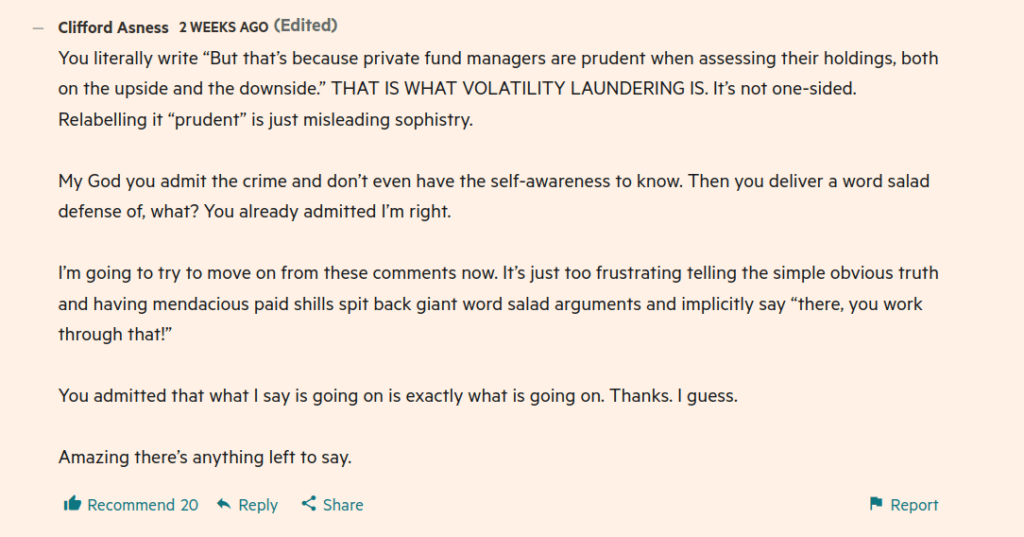

This is the theory of Cliff Asness, the founder of AQR. He even coined the term “volatility laundering,” one of the greatest investing terms ever.

If private equity investors are indeed paying for the lack of real-time prices, how can there be a premium? If you are paying for something, that means the returns have to decrease. The more investors want something, the lower the premium. This is Cliff’s theory:

Unlike Swensen’s PE market, which was primarily about earning extra return, today’s PE market is now seemingly as much about not having to report market prices. That kind of investment should return less over the long term than the appropriate levered public equity benchmark (and I haven’t even gone into the fees on fees on fees). Admittedly, this is educated conjecture. The net of the above could be a smaller return premium for private versus public equity, as opposed to a deficit. But I do stand by my conjecture, and though the magnitude is impossible to be precise about, it’s difficult to imagine the drop-off is not directionally right and nontrivial.

On second thought, the assertion that private markets help you stay disciplined because of the lack of real-time pricing doesn’t make sense. Do you want to invest with a manager who cannot handle facing reality, even if it induces acid reflux and loose motion daily? Isn’t the whole point of being an investment professional that you are smarter than regular people?

You might think that since institutional investors are goddamn smart, they won’t be paying for someone to lie to them. Blake Jackson, David C. Ling, and Andy Naranjo found that private equity investors want to be lied to.

Institutional investors invest in illiquid assets because they prefer mark-to-magic valuations over mark-to-market valuations. Incentives!

The central message of our paper is that some PERE GPs manipulate interim returns in a manner consistent with their investors’ desire for such boosted returns. PERE GPs do not appear to manipulate interim returns to fool their LPs, but rather because their LPs want them to do so. This allows these LPs to report higher returns alongside lower reported volatility in the short term. This catering view of return manipulation is consistent with the overwhelming LP preference to access real estate investments through PERE funds rather than more volatile marked-to-market REITs.

We find markedly little evidence that IRR manipulations hurt GP attempts at raising capital for follow-on funds. In fact, the average GP that manipulates IRRs successfully raises capital for a follow-on fund and manages larger commitments from their LPs.

To further quote Cliff Asness:

That privates are being more prized today, at least on a relative basis compared with the past, for their hiding of the risk. They’re hiding with open eyes.

In the last 5-10 years, there’s been a mad rush into private equity, so much so that institutions were allocating through secondaries at a premium.

For the first time, stakes in big buyout funds are this year on average being sold at “par”, or equal, to their last public net asset value, according to Triago, a company that helps arrange the trades. These stakes have traded just shy of their NAV in recent years. Funds managed by the best-known firms — such as Blackstone, KKR or Carlyle — are selling at a 5 per cent to 7 per cent premium over their NAVs, according to Antoine Dréan, Triago’s chairman.

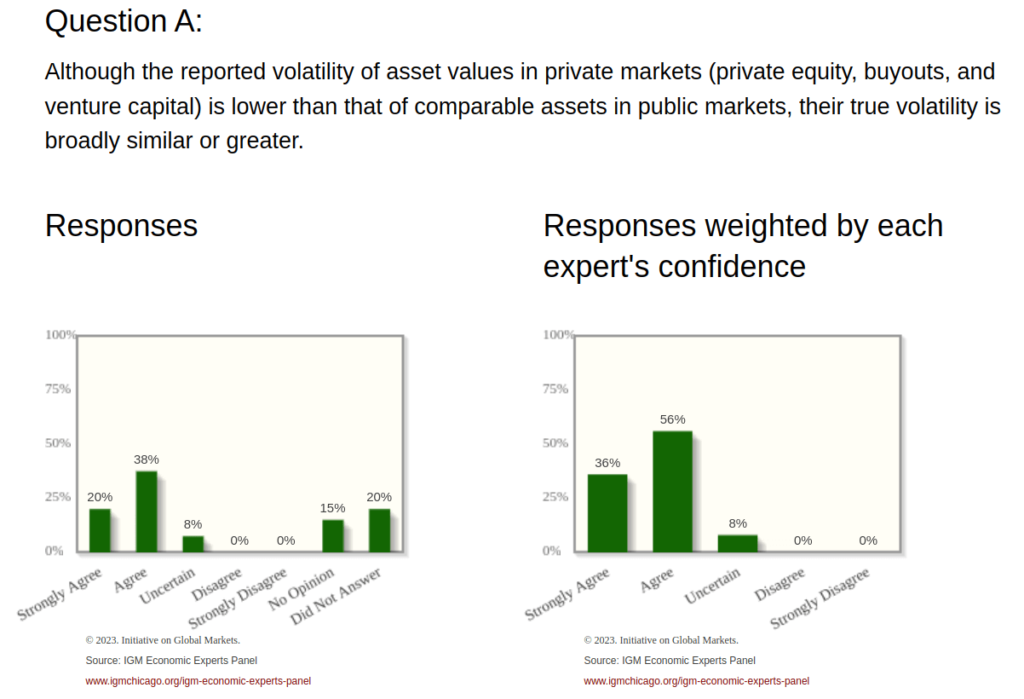

This isn’t a secret, either. Everybody knows, but nobody cares. Here are the responses when an all-star cast of finance professors, including Sheridan Titman, Stefan Nagel, Steve Kaplan, Janice Eberly, John Cochrane, and Campbell Harvey, were asked if PE had lower volatility compared to public markets.

Not everybody agrees that private equity is “laundering volatility.” There was a lively debate in the comments section of FT Alphaville recently. Cyril Demaria, an affiliate professor for private capital at EDHEC Business School, published a piece defending private equity’s valuation practices and made this jaw-dropping assertion, I presume, with a straight face. But I cannot independently verify if Cyril had a straight face when writing the post.

Yes, the ebb and flow is still more muted than what you see in public markets. But that’s because private fund managers are prudent when assessing their holdings, both on the upside and the downside. As a result, the NAVs move more sedately than stock markets — especially when you consider that NAVs are effectively calculated gross of performance fees (the 20 per cent “carried interest”).

Is this approach wrong? It’s pretty clear that public markets overreact to information, and can diverge substantially and durably from their fundamentals. Instead of calling it “laundering volatility”, perhaps private market NAVs actually bring a healthy dose of prudence and reason to an otherwise wildly gyrating financial system? I’d argue that these NAVs should even be seen as a valuable source of independent financial information — although still available on average with a three- to six-month delay.

As luck would have it, Cliff Asness decided to engage in the comments section, and it’s glorious:

In summary, there’s reasonable evidence that private equity is nothing but unlisted small and microcaps with a 2% and 20% fee structure. It’s fair to assume you can replicate private equity returns using publicly listed stocks with leverage. Private equity is also similar to public markets in many ways. Like in public markets, there will always be some private equity fund managers that generate abnormal alpha. But just like in public markets, it’s almost impossible to identify those managers in advance [1, 2].

Given the structure of private equity and its lack of transparency, it’ll be a long time before we have clean data to put this debate to rest. Illiquidity and opacity are a salesman’s best friends.

So much for “smart money.”

Does it really matter?

Yes and no.

No, it doesn’t matter to the private equity funds.

By manipulating returns, private equity funds hide their actual volatility. If you agree that private equity is levered small and mid-cap equities, then how the hell can it fall less than listed equities?

Private equity firms charge 2% of the AUM and 20% as carry. If they understate the volatility, the AUM doesn’t change much. This means they can continue charging a 2% fee on a higher AUM base than they would have if all the assets were market-to-market. Genius!

Yes, it matters if you are an investor.

We saw a real-life demonstration of why this year. Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust (BREIT) is a non-traded real estate investment trust (REIT). On December 2nd, 2022, Blackstone limited redemptions in the fund after investors rushed to sell the REIT. The funny thing is, as of November 2022, Blackstone said that the fund had generated 8.4% while publicly-traded REITs were down 25-30%.

Only 43% of the redemption requests out of the total redemption requests, equal to 5.44% of the AUM were approved in December. In February 2023, only 35% of the ~$3.9 billion in redemptions were processed. Blackstone continued to sell properties and managed to get the University of California to invest $4.5 billion by promising a guaranteed 11.25% return.

On January 19, KKR joined Blackstone in restricting withdrawals in its non-traded REIT fund.

“They love their assets like their children, they really don’t want to write down those assets,” she said. “They are also fundraising, so it’s not really going to help them to write down those assets.”

Imogen Richards, global head of investment structuring at Pantheon Ventures | Bloomberg

Fees

How can anyone write a post about private equity without a pinch of populist pandering?

Private equity is a costly asset class. Funds charge a management fee of 1.5–2% and a performance fee of 20%. But private equity is lightly regulated, and fees aren’t standardized. The fees vary according to the type and size of investors in the same funds. Savvy investors can negotiate the fees and have private contracts that aren’t disclosed.

Apart from the headline fees, funds can also charge additional fees such as transaction fees, portfolio company fees, and monitoring fees. Ludovic Phalippou and his co-authors estimated that between 1995 and 2014, private equity firms charged $20 billion in such fees. All these fees came from the companies whose boards were controlled by the same private equity funds In the case of fund of funds, there’s an additional layer of funds due to the structure.

All the debates over the performance of private equity are partly due to the high fee structure. As I’ve summarized so far, some argue that private equity delivers alpha net of fees, and others argue that it doesn’t, and I don’t think this debate will be settled anytime soon. You have to draw your own conclusions based on the available evidence.

My view is that the benefits of private equity have been overstated. The realities of private equity are much the same as fund management in public markets. Most managers are extracting rents, and a few managers that are hard to identify in advance add value. The superficial arguments touting the advantages of private markets that paper over these realities never cease to amaze me.

Then there’s the carried interest loophole in the United States. This taxation quirk allows private equity managers to treat carried interest or carry as capital gains instead of considering it as salary. Capital gains tax at 20% is far less than the individual tax rate of 37%. The private equity lobby has thwarted repeated attempts to close the loophole.

In the salaciously titled paper An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & The Billionaire Factory, Ludovic Pahlippou notes that PE firms made over $230 billion in carry that went to a small group of rich people:

Hence, although the latest decade of funds that terminated their investment period (2006-2015 vintages) returned about the same as public equity benchmarks (about 11% p.a.), their managers still received $230bn of Carry, alongside a lot of other fees. Most of this money went to a relatively few individuals, mostly founders of large PE firms (Ivashina and Lerner (2019)). I find that the number of PE multibillionaires rose from 3 in 2005 to 22 in 2020, and are mostly affiliated to large PE firms.

One of the sales pitches of private equity is that it reduces the principal-agent problem rife in the public markets. But going by the numbers, it seems they’ve done a brilliant job of tilting the rents generated away from the principal towards the agent.

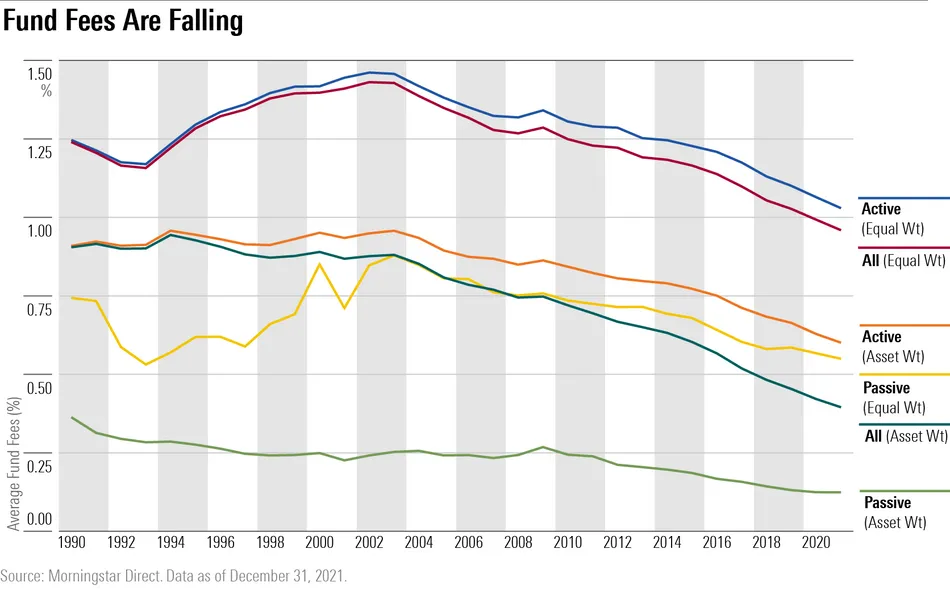

Why haven’t the goddamn fees come down?

In the last 15 years, fee compression in mutual funds, ETFs, and hedge funds has been like the law of gravity.

But private equity fees have bucked this trend because of the sheer demand:

A Dutch pension sector source involved in the selection of private equity mandates told IPE about his recent visit to a private equity manager that was looking to raise €1.5bn for a fund. He says: “This manager already had €30bn in commitments. So if APG, PGGM or MN back out of a deal because of the fees, that means nothing to them.”

Cost saving in private equity also remains a difficult exercise as fees are negotiable, in reality, only at the time of the investment, Staub notes. “Nobody is really negotiating with private equity managers, fearing that they may lose access to the private equity firm,” he adds.

So does private equity add value?

Michael Jensen, the famed economist and one of the stars of management textbooks you hated reading, wrote in a provocative piece in 1987:

The publicly held corporation has outlived its usefulness in many sectors of the economy.

By resolving the central weakness of the public corporation—the conflict between owners and managers over the control and use of corporate resources—these new organizations are making remarkable gains in operating efficiency, employee productivity, and shareholder value.

He wrote that the private markets, by fixing many of the ills that plague public markets, would “eclipse” the public markets.

Have they?

Put another way, the question is, does private equity add value?

Let’s start with the key sales pitch of private equity. By taking companies private, they shield them from the short-termism that plagues public markets. Since private equity companies don’t have to worry about quarterly results, pleasing shareholders, or using the word “synergy” 63 times in management conference calls, private equity managers allow companies to focus on growth.

But do they?

The median holding period of private equity assets is less than 5 years, after which they’re either taken public or sold.

So, how does this solve the problem?

In the same way, dipping your hand in a can of Fevicol fixes a broken hand.

In a delightful talk, Mihir Desai, professor at Harvard Business School and author of The Wisdom of Finance, summed it up better than I can:

Private equity becomes a major asset class in the last 20 years. Why? In part, don’t deal with all that garbage. I’ll come along, I’ll be one big owner. I will solve this for you, and I will sit on you like a hawk and watch you like a hawk. That’s the private equity answer. Is that a salvation to this problem? Turns out they have their own problems cuz guess what? They’re gonna monetize their investment by doing what taking their company public back into that game right there, and they’re gonna make themselves look particularly good right before they do that.

Everything in finance is one big informational problem, that’s what this whole game is about. The people who you think of as being terrible activists and short sellers those nasty people, maybe they’re the heroes. They’re the only ones who will tell you the negative news, everyone else is positive. They may be the ones who will say, no, wait a second, “it’s a liar.”

Now, of course, they’re not really heroes because they have their own incentive and information problems. Because they are allocated capital, and they have to get their returns for their funders. Life is one big daisy chain of principal-agent problems.

Mihir Desai

So are all private equity firms rent-seeking vampires that are sucking our economies and communities dry?

After analyzing 9,800 US private equity buyout transactions from 1980 to 2013, Davis et al. (2019) more or less concluded that the answer to the question, “Is private equity good or bad?” is “it’s complicated.” The effects vary based on economic conditions, deal type, industry, and time. But here are some high-level observations:

- In the case of private-to-private acquisitions, employment rose by 13%.

- In the case of public-to-private acquisitions, employment fell by 13% and by 16% in the case of the acquisition of specific divisions.

- Productivity rose by 7.5%, leading to increased revenues.

- Productivity increases more in acquisitions when credit conditions are tight and less during easy credit conditions.

But at the risk of stating the obvious, such broad analyses hide substantial variation. Let’s look at studies that analyze the impact of private equity on specific industries.

Healthcare

Since the 2008 crisis, the healthcare industry has been a favorite of private equity firms. Studies by Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt have shown that PE firms have been buying up hospitals, emergency rooms, physician staffing firms, medical debt collection agencies, and hospital management software providers and rolling them up. This has had a devastating impact. A study by Gupta et al. (2021) found that private equity owned nursing facilities have higher deaths, higher charges, fewer caregivers, an increased prescription of antipsychotic medication, and a precipitous decline in the quality of care. This investigative piece in the New Yorker by Yasmin Rafiei on private equity owned nursing homes is heartbreaking.

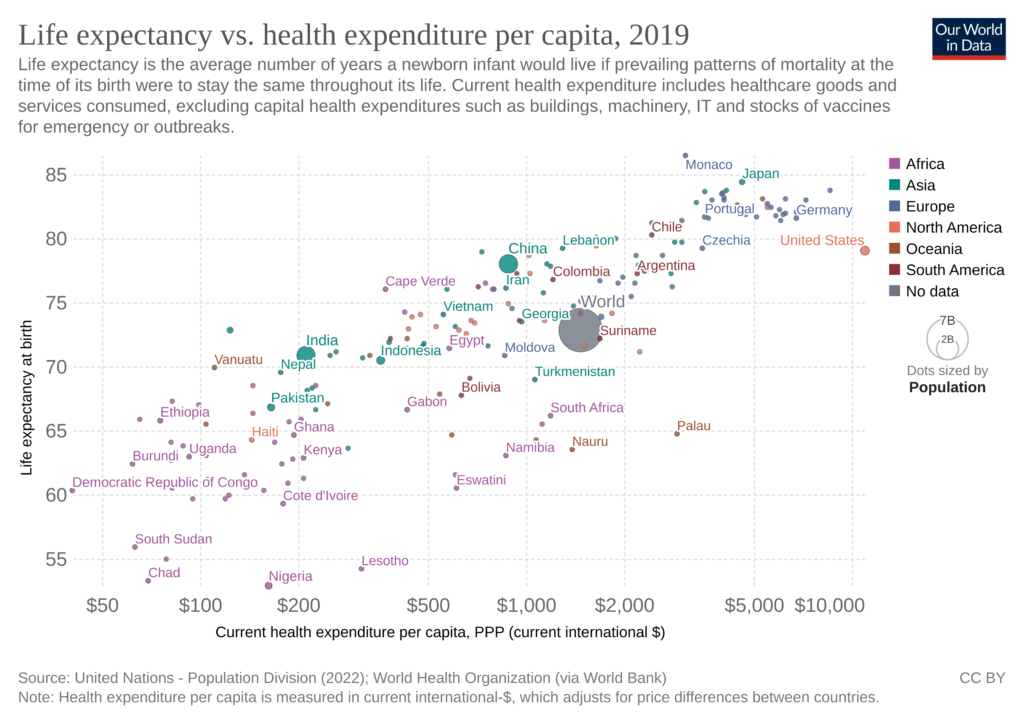

Other studies have come to similar conclusions. Private equity ownership leads to higher insurance claims, higher costs, lower quality care, and more injuries. This is depressing considering the fact that US citizens spend the most on healthcare.

Housing

The recent inflationary surge led to a dramatic increase in the cost of living worldwide. Along with everything, housing prices and rents rose sharply, affecting the poor and low-income households the most. Since housing is one of the biggest household expenditures, there was widespread outrage over rising rents. As people looked for the cause, private equity firms like Blackstone, Brookfield, and KKR emerged as the villains. They were subject to intense scorn, so much so that BlackRock had to release a statement.

Unlike healthcare, private equity involvement in housing is still small.

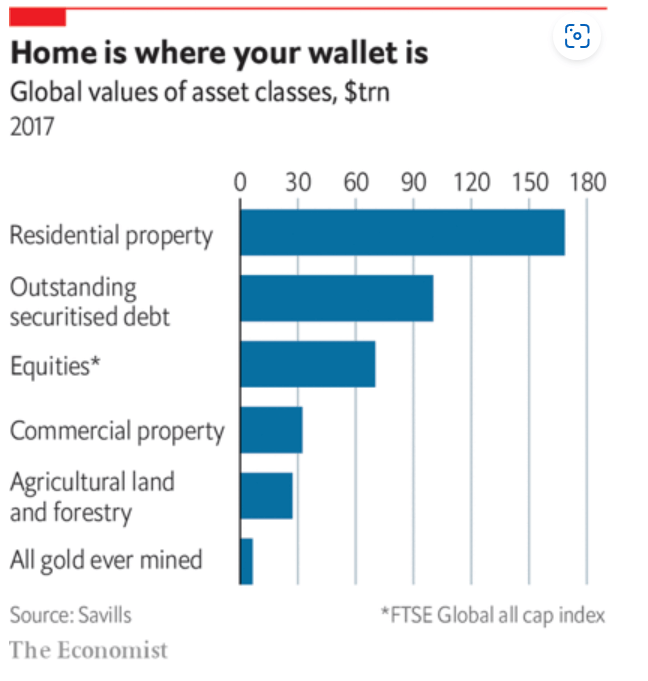

Private equity firms have long been in real estate since it’s the largest asset class on the planet.

But they started getting involved in housing after the 2008 crisis. As home foreclosures hit a record high, private equity firms bought single-family and multifamily rentals. Contrary to all the headlines about institutional investors gobbling up housing, institutional investors own just 1-5% of rental homes in advanced economies. They might be big in some sub-regions, but they’re still small overall.

But the rate at which they are acquiring homes has been rising, and given the ever-increasing pools of large investors, this will only grow over time. The affordability crisis in housing isn’t new; it’s been decades in the making. The crisis has many country-specific causes involving a toxic mix of politics, regulations, taxation, and supply issues. But of the houses private equity firms own and manage, they’ve become institutional slumlords. They’ve jacked up rents, introduced hidden charges, exorbitant fines, cut costs on maintenance, and forced evictions.

Media

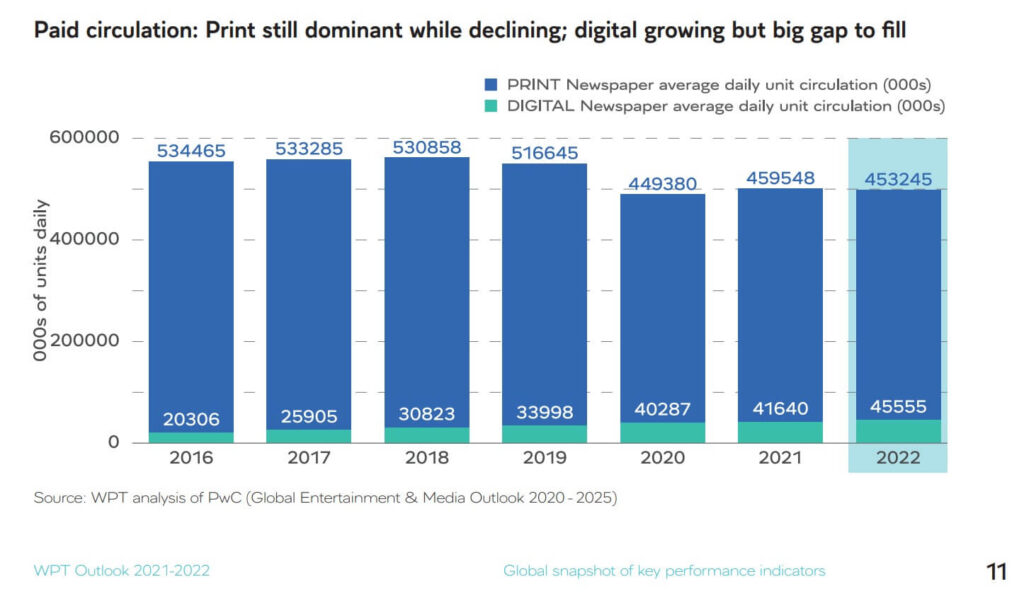

The moment the internet unbundled news and the audience, traditional news media began its death spiral. Digital media was supposed to be the savior, but news media could not compete with Google and Facebook. The result is that newspaper circulation and revenues have been in a secular downtrend across much of the world, especially in local news media. There have been countless closures, layoffs, mergers, and acquisitions.

Private equity tends to be active in distressed industries, and media is no different. Private equity ownership of US newspapers increased from 5% in 2001 to 23% in 2019. Ewens et al. (2022) analyzed the impact of private equity ownership of newspapers, and the results are depressing. Private equity ownership leads to a reduction in local news stories, a decline in circulation, and increased layoffs of reporters and editors. The fallout of this is that voter turnout is low in local body elections.

Private equity is satan incarnate!

- Eaton et al. (2018) show that private equity ownership of colleges leads to lower graduation rates, earnings, and student loan repayment rates.

- A study by Brian Ayash and Mahdi Rastad shows that the bankruptcy rate of leveraged buyout (LBO) firms is 18% higher than that of non-LBO acquisitions.

- Brian Ayash and Edward Egan show that private equity acquisitions lead to lower patents, reduced grants, and higher sales of existing patents.

- The carried interest loophole has survived decades of assault thanks to the formidable private equity lobby. Dare I say legislative capture?

- Private equity has been on a buying spree, buying everything from veterinary practices to pet care centers. The evidence shows that this has led to the closure of practices affecting farming communities that depend on local vets and a sharp increase in drug prices.

Private equity is almost an angel!

These are a few of the most egregious examples of how the incentive structure of private equity is geared towards exploitation and rent-seeking. But there’s positive evidence of private equity ownership too:

- Studies by Ross et al. (2021) and Bernstein et al. (2017) have shown that private equity was instrumental in containing bank failures during the 2008 crisis. The banks acquired by private equity performed much better than comparable acquisitions.

- A recent paper by Howell et al. (2022) showed that acquisitions of airports by private equity led to marked improvements in passenger count, number of flights, airlines, and quality of service.

- A study by Fracassi et al. (2020) showed that consumer product companies acquired by private equity see an increase in sales, products, and revenues.

- Cohn et al. (2016) show that safety violations and workplace injuries decrease when private equity firms acquire companies.

On the one hand, critics paint private equity firms as blood-sucking vampires that saddle companies with debt and strip them for parts. On the other hand, the supporters argue that by instilling modern management practices, operational expertise, trimming the fat, and easing financing constraints, private equity adds value.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere in the middle. If you want to be critical of private equity, you can make an extreme case that it should be illegal, like Benjamin Braun.

This line of thinking leads to the question of why private equity exists in the first place.

The easy answer is that private equity is another form of risk capital. A more theoretical premise is that some companies are better off remaining private and can do well with the management and industry expertise that private equity can bring. While researching this piece, I had an “aha” moment when I read the title of this Brookings essay, “Private equity Investment as a Divining Rod for Market Failure.” I realized private equity thrives because it’s good at exploiting market failures and legal and regulatory loopholes.

- Private equity firms tend to aggressively exploit payment loopholes in healthcare, leading to higher costs.

- Private equity-owned educational firms are good at squeezing govt benefits like federal educational aid.

- Until recently, private equity had all but escaped the antitrust spotlight, even as PE firms consolidated large swathes of industries and amassed incredible market power.

- It’s remarkable that private equity has avoided being regulated by the SEC in the US, despite being around since the 1970s and having over $10 trillion in AUM.

- The private equity industry has its own senator—Kyrsten Sinema. After receiving millions in campaign donations from private equity firms, she repaid them by torpedoing a recent attempt to close the carried interest loophole.

These are a few examples of how private equity is good at exploiting loopholes and market failures. Continuing with the same line of thinking as to why private equity exists, there’s another perspective. Take the example of the news media. This space is near and dear to my heart. I track it closely because, as the slogan of the Washington Post sums it up, “democracy dies in darkness.” But, news media has been in a secular decline across much of the world. Except for large organizations like the New York Times, The Times of India, and the Financial Times, everybody else is struggling or dying.

Now, think of a hypothetical world where private equity and distressed funds didn’t exist. What would happen to news organizations? Because there is evidence that private equity firms offer distressed companies a new lease on life or delay their impending death. Here’s an excerpt from this paper by Michael Ewens, Arpit Gupta, and Sabrina T. Howell:

The bright side is that private equity ownership leads to higher newspaper survival rates and more digital content, consistent with investing to help to turn around and modernize a struggling industry. A downside is that civic engagement appears to decline because readers of newspapers and the outlets that rely on their reporting have less information about local government. The high-powered incentives to maximize profits that accompany private equity ownership may be poorly aligned with the public good characteristics and implicit contracts involved in reporting about local government.

Local Journalism under Private Equity Ownership

Is it better if such ailing companies die a quick and clean death or delay their demise while employing millions of people? Idealistic arguments that news should be a public good funded by taxpayers are beside the point. We don’t live in an ideal world. The issue with passing moral judgments is that it leads you down the path of thinking about such messy questions. Either that or I am complicating this whole thing. There’s more to this than just my naive simplification.

Climate change as an asset class

Except for academics and interested observers, most discussions about private equity are about the fees and performance of private equity. Fees and performance are important factors, but it’s important to take a wider lens when thinking about an industry that has attracted trillions from public pensions belonging to teachers, firemen, policemen, and other government and blue-collar workers. Aside from the financial markets, it is important to examine private equity from a political economy standpoint.

It took some time, but there’s widespread acceptance, even among skeptics, that we’re all going to die from climate change. If we are to have a fighting chance of not dying, we have to transition away from carbon-intensive fuels to green energy. Both the public and private sectors have critical roles to play in this transition, and this is where asset managers like private equity come into the picture. Before we get to the role of asset managers in us not dying, I think it’s important to understand how asset managers and private equity, in particular, became such important actors in our society.

With the doubling of global assets under management (AUM) in the last decade to over $100 trillion, asset managers have become the new masters of the universe. The growth is the result of several well-known factors, such as rising incomes, the growing penetration of retirement saving vehicles, the growth of the rich, the shift away from defined benefit pensions to defined contribution pensions, and the rise of large cash pools such as sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and corporate treasuries.

But there are also several structural reasons. Across much of the developed and developing world, there has been a shift from bank-based finance to shadow banking or market-based finance, where security markets take center stage in credit creation and new forms of shadow money. This long-term structural change accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis as regulators forced banks to shrink their footprint.

Shadow banking is a term to describe non-bank financial intermediation that occurs outside the banking system. Asset managers, money market mutual funds, private equity, private credit, hedge funds, non-bank financial institutions, pensions, and insurance companies, among others, are the primary actors. Benjamin Braun’s “asset manager capitalism,” Daniela Gabor’s “Wall Street consensus,” and Perry Mehrling’s “money view” are important frameworks that explain this new paradigm. You cannot understand the evolution of the global financial system without reading the papers and books and listening to the talks of these three brilliant economists.

Shadow banking has been around in one form or another for a long time, but the shadow banking system as we know it today originated in the 1970s. The system originated from political and regulatory decisions made in the United States and Europe. A few key reasons:

- The move to separate finance ministries and central banks. This push for central bank independence and the move by sovereigns to raise money from the markets led to the birth of repurchase agreement (repo) markets.

- The inflationary shock of the 1970s and interest rate ceilings on deposits (Regulation Q) led to the birth of money market mutual funds and the high-yield bond (junk bond) market.

- The creation of securitization structures and derivatives like credit default swaps in the 1970s and 1980s

- The “neoliberal assault on the old traditional welfare state,” as Daniel Gabor terms it. This, along with the reduced capacity of the state to tax rich individuals and corporations, led to people relying on pensions and insurance companies to save for future uncertainties as opposed to the state. This led to the rise of institutional cash pools like large corporations, pensions, broker-dealers, and insurance companies.

- A global hunt for yield.

- Shadow banks rose to mediate the search for safety by large institutional cash pools and the search for yield by levered investors like hedge funds.

- The shadow banking system, a crucial piece of the shadow banking universe, developed with the active involvement and backstop of the Federal Reserve.

- A deliberate political project to export the American model of market-based finance around the world.

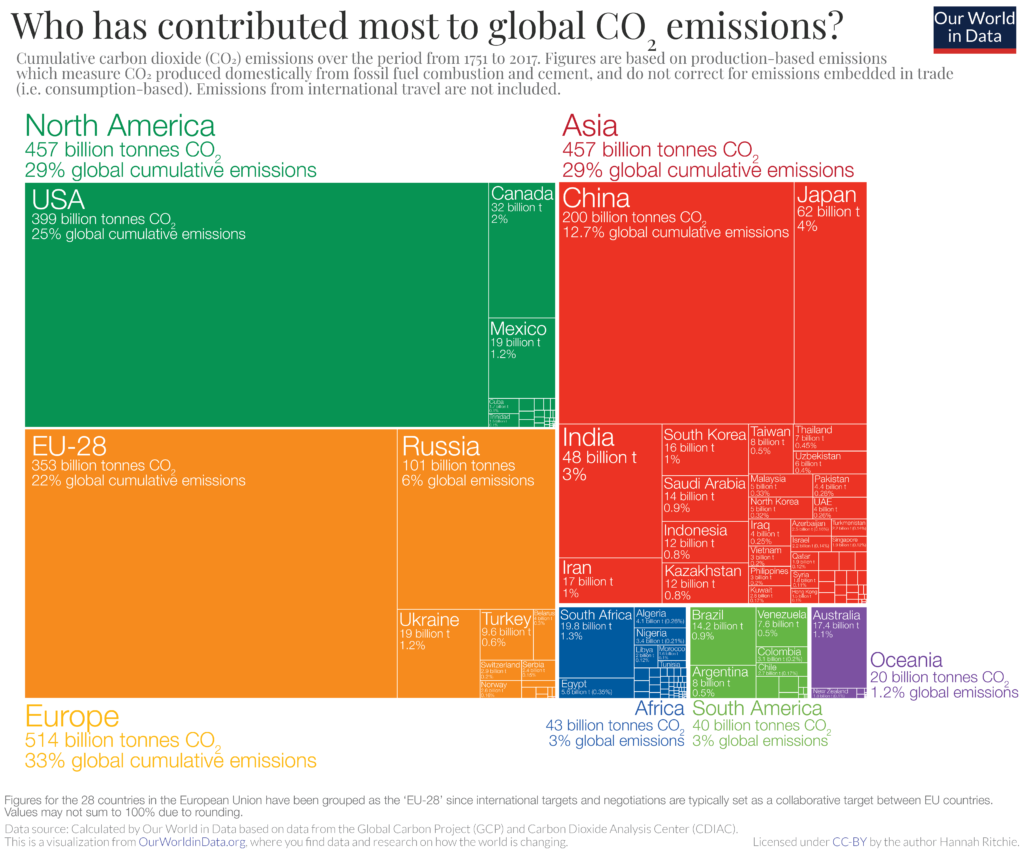

But coming back to the topic, there’s a profound contradiction at the heart of the green transition. The rich countries got rich because they burned their way to prosperity. They are now trying to push poor and developing countries that are starting their development journeys to cut emissions aggressively and green their economies.

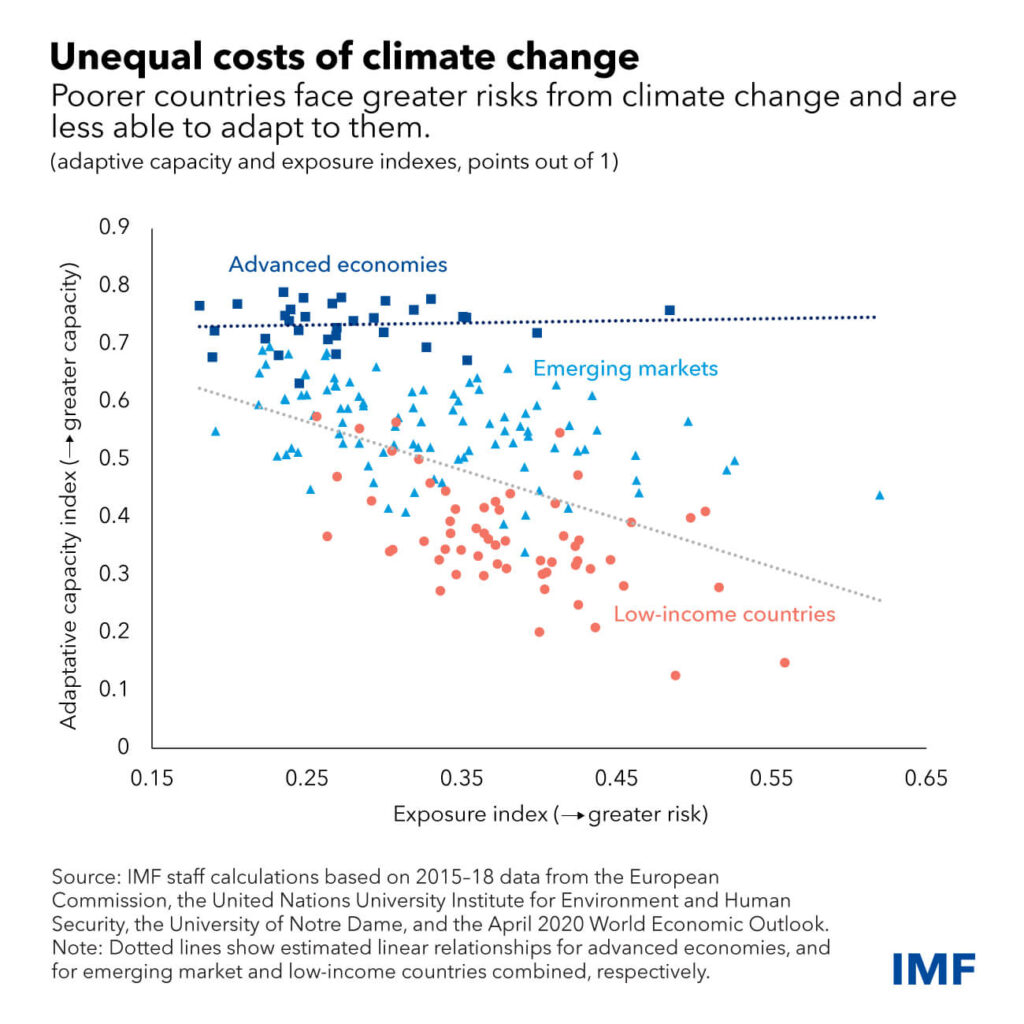

The irony is that the poorest countries, which have to grow the most and are financially the weakest, face the disproportionate burden of climate change.

All the promises made by the rich countries to provide finance to help the poor countries have been just lip service. We’ve known about the devastating impact of climate change for decades, but we chose to bury our heads in the sand. We kept delaying action, and the bills have now come due.

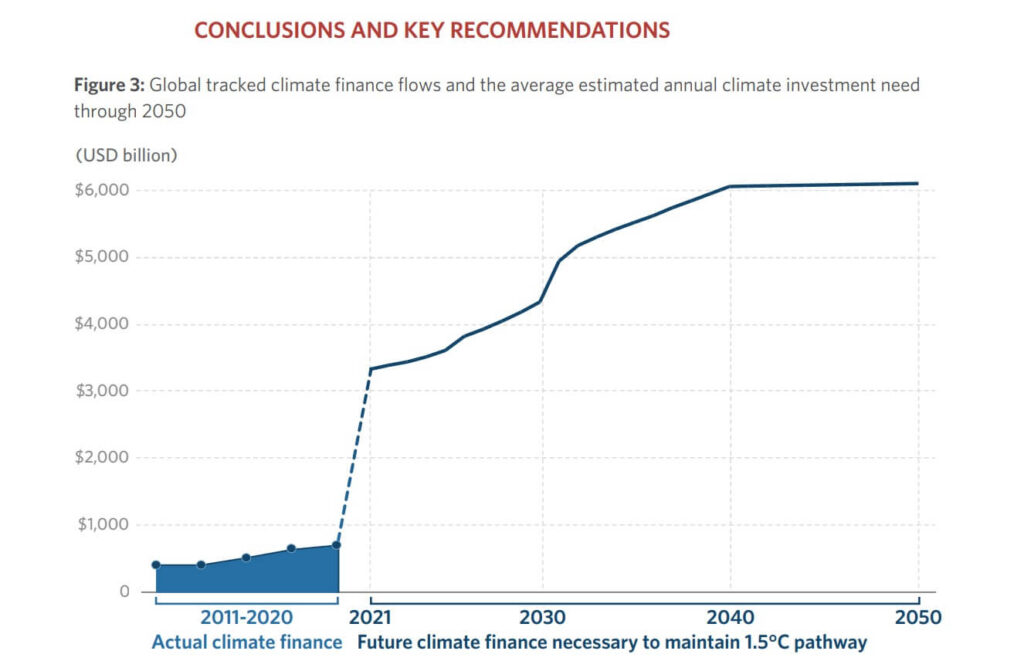

The cost of transitioning to a low-carbon economy is astounding. The best estimates put the number anywhere from $4 to $9 trillion a year. Remember, these are estimates. Humans have always had the predictive capabilities of a drunk monkey throwing darts while riding a horse with Ray-Ban sunglasses.

So, how much are we spending currently?

A drop in Varthur Lake!

The problem is, we don’t care. This Saturday Night Live segment best summed up our collective apathy towards dying:

We don’t really worry about climate change because it’s too overwhelming and we’re already in too deep. It’s like if you owe your bookie $1000 it’s like okay I’ve gotta pay this dude back. But if you owe your bookie a million dollars, you’re like, ‘I guess I’m just gonna die?

Colin Jost

The rich countries can afford to do at least something. In the last few years, America and Europe have taken breaks from their year-long political carnivals, and clown shows to do something. The US passed the $370 billion Inflation Reduction Act, while Europe announced the €210 billion REPowerEU plan. It’s nowhere close to enough, but it’s something. The poor countries, on the other hand, are buggered. According to an OECD estimate, the gap between what low-income countries need and can afford runs to $3.7 trillion per year. Again, these are estimates; the actual funding needs are orders of magnitude higher.

The rich countries owe the poor countries. In an ideal world, they would’ve helped the poor countries transition to greener economies and cope with the effects of global warming. Even though poor countries are least responsible for global warming but at the greatest risk from it, the rich countries have abdicated their responsibility.

To make matters worse, emerging and developing economies are facing severe fiscal constraints, thanks to COVID-19. According to the IMF, 60% of low-income countries are in or at risk of debt distress. These countries also have unreliable access to capital markets and face a high cost of capital.

Instead of helping, the rich countries are resorting to old tricks. They’re once again peddling private finance and markets as the solution. It doesn’t matter that they’ve been pushing the same thing since the 1990s and that it has failed. This time, it comes in new and improved neoliberal packaging. Leaders like John Kerry and Mark Carney and organizations like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the G20 are promising a flood of trillions from global institutional investors if poor countries can make it worth their while. It’s interesting to note that Mark Carney is the chair and head of transition investing at Brookfield Asset Management, an $800 billion private equity giant.

How?

Institutional investors with hundreds of trillions under management are looking for investible opportunities. The problem is that low-income and emerging countries are fraught with political, social, and economic risks. At the same time, these countries need trillions to transition to a green economy.

Institutional investors will be more than happy to invest indevelopment projects if developing countries can improve the risk and return profiles of the projects.

How?

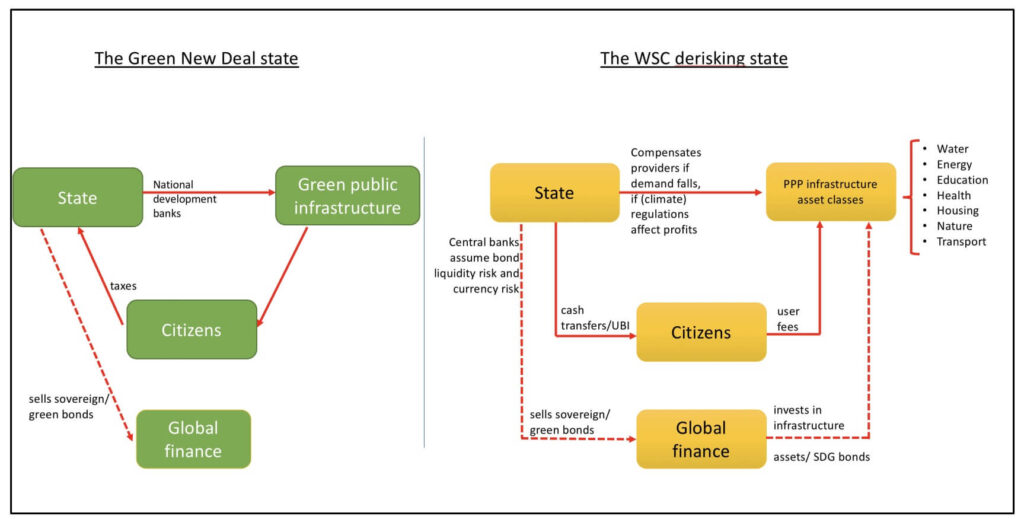

By providing guarantees against political, demand, climate, currency, and bond market risks for institutional investors by moving them to their own balance sheets. Daniel Gabor dubs this the “de-risking state” in the Wall Street Consensus.

Here’s an excerpt from the IMF’s sustainability advisory group:

Governments, development financial institutions, and the private sector increase their collaboration to develop a pipeline of bankable projects. Development of such a pipeline must include an emphasis on private sector engagement during the project preparation phase, as well as mechanisms to advance credibility and reduce uncertainty of government commitments, plans, and policies (including offtake risk for renewables).

Governments employ blended-financing solutions to help unlock financing and address risks for long-term investments.

In short, private financiers will be more than happy to finance the green transition in low-income countries if they don’t have to take risks. How gracious of them!

It’s remarkable that private financiers like Larry Fink openly ask governments, development banks, and multilateral institutions to insure them against market risks.

We need global solutions and international organizations that are willing to mitigate the risks of investing in emerging markets, Fink said.

Larry Fink — Reuters

If we’re going to attract the hundreds of billions of dollars of private capital for brownfields and other sustainable projects in the emerging markets, we need more solutions like those used in mortgage-backed securities where some degree of losses is absorbed before they impact private investors.

Carolyn Sissoko, professor of economics at UWE Bristol, hits the nail on the head:

Our current financial markets are characterised not just by unreliable liquidity in sovereign debt markets, but also by a zeitgeist that favours what is best described as crony capitalism in advanced economies, when structural financial instability is transformed into a reason to socialise losses and bail out unsuccessful companies. The discussion of the «de-risking state» above is part of this phenomenon, and we have seen this in the responses to financial crises in 2007–2009 and in 2020.

Carolyn Sissoko — Making the great turnaround work, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

After the bailout of the banking system in 2008 and the bailout of the bond market and shadow banking system in 2020, moral hazard is no longer a bug but a feature. Unlike in 2008, there’s no shame in asking for handouts and guarantees from the state. The private financiers think they are entitled to it now.

This is where private equity comes into the picture. I know this is a roundabout way of getting to specifics about private finance, but this is an existential issue, and it’s important to understand the historical context of how asset managers became so dominant.

Asset managers such as mutual funds, hedge funds, and private equity funds hold trillions of dollars worth of fossil fuel assets. Given the dramatic asset growth, these asset managers have become the largest owners of large swathes of listed and unlisted equities and bonds. They also wield significant influence through their ability to influence the company’s management through shareholder voting and engagement.

So, how’s this working out?

What’s financialization and privatization by another name?

In pushing private finance as the solution to climate finance, advanced economies are repackaging the Washington consensus—more financial liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. In short, more markets, less state! It doesn’t matter that these policies have had mixed results.

Advanced economies and multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the IMF are pushing poor countries to shift from bank-based financial systems to securities-based, market-oriented financial systems. Private finance would be more than happy to funnel trillions into development as long as they have access to:

- Liquid financial markets and the ability to buy and sell.

- Derivatives and swap markets to hedge default and currency risks.

Alignment of the financial system with climate and development objectives also means developing and deepening domestic financial markets and banking systems within EMDEs to help mobilize domestic resources. Developing and deepening these markets can help minimize balance of payments vulnerabilities that could arise from large external inflows of financing for climate change mitigation and adaptation. MDBs will be particularly critical in supporting an agenda along these lines, through providing technical assistance and advising on blended-financing aspects to share risk and build capacity, as outlined in the next subsection

IMF

The key premise of market-based financial systems is that anything can be turned into tradable securities through securitization, including development and nature itself. It’s a profound irony that the prevailing consensus to tackle climate change is to transform it into an asset class.

Under pressure to do more, asset managers and developmental institutions have pushed for and adopted ESG ratings to determine the sustainability characteristics of their portfolios and projects. The issue is that there are no accepted sustainable/green taxonomies. Private ESG raters are also unregulated and opaque, making their ratings useless as things stand today. This increases the risk of ESG rating shopping, greenwashing, and sustainability washing.

In pushing private finance to deliver a carbon transition, multilateral institutions like the World Bank are ignoring the fact that asset managers and pensions aren’t non-profits. They have return expectations and targets. The issue is that not all projects can deliver the returns private financiers seek. Necessities like affordable housing, healthcare, and education shouldn’t either.

Investment will be needed not just in the places where markets can make use of the profit motives of firms alone. Funds will also need to flow into projects and investments that yield the highest social returns for people and communities, and sometimes in the absence of direct commercial interests.

Carolyn Sissoko — Making the great turnaround work, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

This opens up the risk of cherry-picking the projects that asset managers like, turning poor countries into all-you-can-eat buffets for private financiers.

Crucially, investors don’t want to buy just anything. Given a pool of public assets to choose from―hospitals, utilities, transit―private investors will cherrypick those with steady revenue streams from wealthier and more concentrated groups of citizens. Absent strict regulation, infrastructure privatization usually also permits an asset’s new owners to raise prices, lay off staff, and diminish service quality―all to maximize revenues and cut costs. Asset manager Macquarie’s ownership of an English water utility, for example, left customers paying higher prices while letting raw sewage leak into the country’s rivers, while the proposed deregulation of India’s electricity distribution sector has sparked protests over fears that it will degrade rural electricity provision and harm electricity sector workers. While the private sector profits from serving the privileged, the public sector loses money serving everyone else. This segregation is by design.

Advait Arun- Securitizing the Transition

If poorer countries follow the lead of the G20 and the World Bank, they risk subordinating their developmental needs and sovereignty to the need for returns of private finance. This will further entrench the structural power of finance.

Financialization also subjects poor countries to the risks posed by hot money flows. The same flows led to devastating financial crises in Latin America and Asia in the 1990s. These risks won’t go away even if institutional investors finance these assets through local currency-denominated bonds. The original sin will morph but won’t go away.

Major EME governments have gradually reduced their reliance on foreign currency debt by borrowing more in their own currencies overall. They have also encouraged foreign investment in their domestic market, especially in local currency bonds. As a result, EMEs now finance more of their external debt in their own currency than was the case in the early 2000s. At the same time, depreciations in EME currencies often reduce returns to foreign investors, who sell local currency bonds in periods of stress. Even when EMEs rely less on foreign currency borrowing, they continue to face volatile capital flows.

Onen, M., Shin, H. S., & Peter, G. V. (2023, February 21). Overcoming original sin: insights from a new dataset. Overcoming Original Sin: Insights From a New Dataset. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1075.htm

By pushing more market-based solutions, private finance is seeking to financialize and securitize development and nature itself.

So, how’s all this working out?

Not great!

Despite increasing evidence that private finance isn’t an unalloyed good without strong governance, legal protection, local expertise, international regulatory frameworks, and domestic protections, rich countries continue to push market-based finance as the solution to save the planet.

Back to the asset managers

By virtue of their ownership of fossil fuel assets, asset managers like private equity firms are at the heart of the green transition. While there’s growing literature [1,2,3,4] on the effects of increasing ownership of public equities by asset managers, little attention has been paid to private equity, and I hope this changes. With ~$10 trillion in assets, private equity is no longer a marginal player in the global economy. The popular yet sterile view of private equity funds as buyers and sellers of private companies and as non-bank lenders is incomplete.

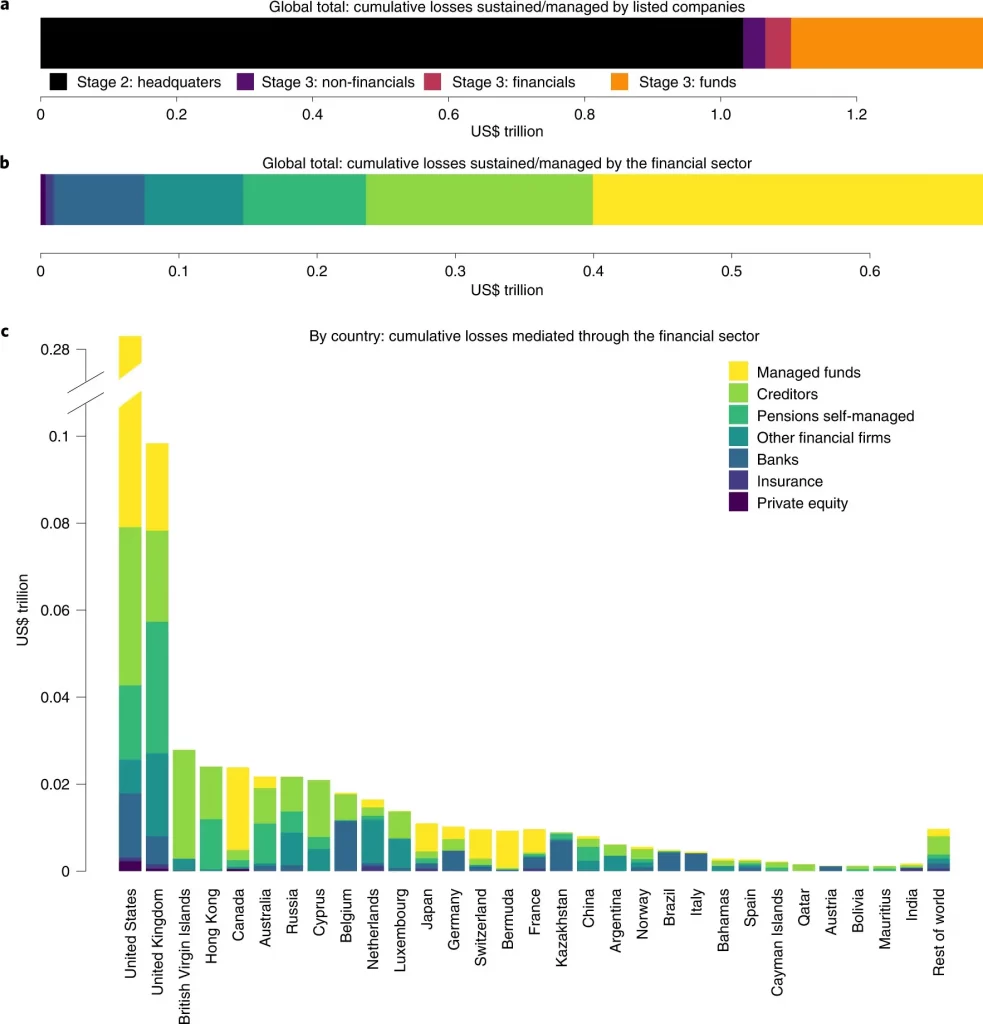

Semieniuk et al. (2022) traced the ultimate ownership of 43,439 oil and gas assets. They found that investors, through funds and pensions, are at risk of significant losses. In this image, private equity and pensions are broken out separately, but pensions, in turn, allocate to private equity funds.

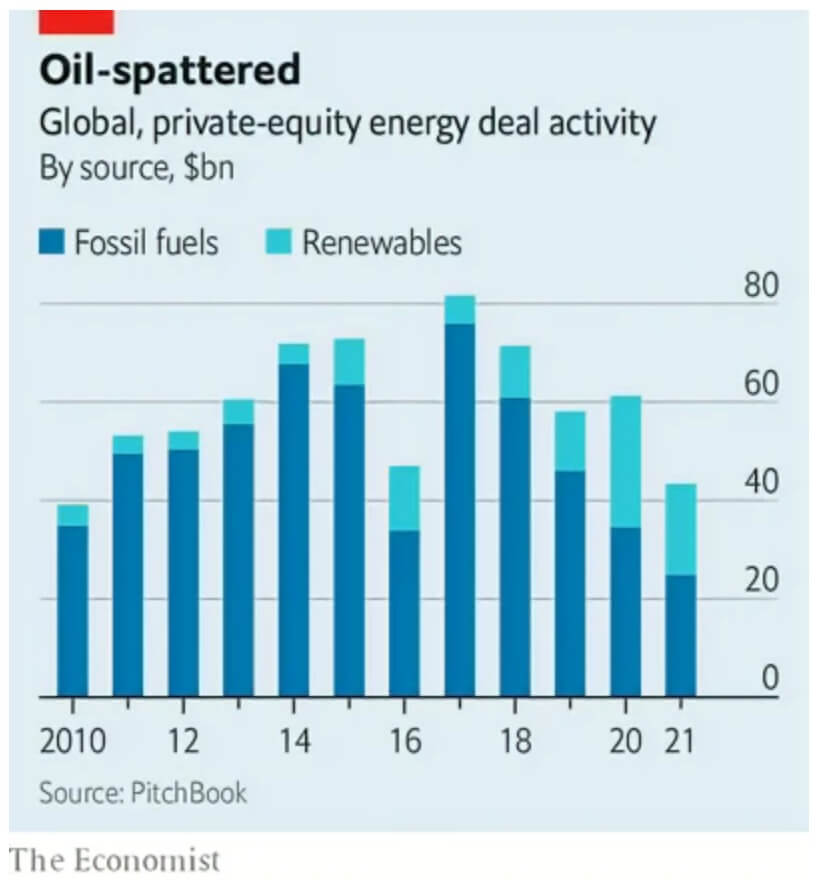

Oil and gas companies are under intense pressure from shareholders to stop choking the planet. The pressure is forcing these companies to sell assets to appease shareholders. As of last year, assets worth $140 billion were up for sale. In 2021 and 2022 alone, private equity firms acquired oil, gas, and coal assets worth over $60 billion. According to the Private Equity Stakeholder Project (PESP), private equity firms have invested $1.1 trillion in energy assets since 2010, mostly in fossil fuels.

According to some estimates, $1–11.8 trillion worth of oil, gas, coal, and untapped reserves are at risk of being stranded. Assets that cannot earn economic returns due to changes in regulations, demand, supply, or disasters are called “stranded assets.” The risk is that private equity firms are sizable investors in distressed companies and assets.

To make things worse, the oil and gas industry earned over $4 trillion in profits in 2022, compared to an average of $1.5 trillion in recent times. There’s also the risk of spiking oil prices if there’s a disorderly energy transition, which is very probable. Given the “profit at any cost” motive of the private equity industry, will it impede decarbonization? That would be a fair assumption.

BP announced a scaling back of its climate goals last month as it unveiled record annual profits in 2022 after oil prices surged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The company’s target to slash oil output by 40 per cent by 2030 — a strategy announced amid a historic oil price crash in 2020 — was reduced to 25 per cent.

FT

Everybody is naked in hamam

We’re all stupid, its just that we haven’t realized it yet.

Concluding this very short piece

Do we need private equity, is it a scam, or is it downright illegal? Like everything, there are positives and negatives. The million-dollar question is if the negatives outweigh the positives. My view is that there are significant and negative externalities that policymakers and regulators ignore.

I’ll leave you with these snippets from Luigi Zingales, professor of entrepreneurship and finance at Chicago Booth.

The first is from his 2015 presidential address at the American Finance Association (AFA):

When does finance help ordinary people and when does it take advantage of them?

We cannot argue deductively that all finance is good. Yet, we do not want to fall in the opposite extreme that all finance is bad or useless. To separate the wheat from the chaff, we need to identify the rent-seeking components of finance, i.e. those activities that while profitable from an individual point of view are not so from a societal point of view.

This is from a 2015 article on the same topic:

We should acknowledge that our view of the benefits of finance is inflated. Although there is no doubt that a developed economy needs a sophisticated financial sector, there is also no theoretical reason or empirical evidence to support the notion that all the growth in the financial sector in the last 40 years has been beneficial to society. In fact, we have both theoretical reasons and empirical evidence to claim that a component has been pure rent-seeking. By defending all forms of finance, by being unwilling to separate the wheat from the chaff, we have lost credibility in defending the real contributions of finance.

Funny, until it isn’t!

References and further reading

Papers and articles

Investing in private equity by Andrew Ang and Morten Sorenson.

The Economist special report on private markets.

When the Tailwind Stops: The Private Equity Industry in the New Interest Rate Environment, edited by Victoria Ivashina

Evaluating investments in unlisted equity for the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) by Trond Døskeland and Per Strömberg.

The Hazards of Using IRR to Measure Performance: The Case of Private Equity. by Phalippou, Ludovic.

Demystifying Illiquid Assets: Expected Returns for Private Equity by Antti Ilmanen, Swati Chandra, and Nicholas McQuinn.

Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting by Erik Stafford. Pushback against this study by Christine Hamilton.

Private Equity Replication with Leveraged Small-Cap Value Stocks by Brian Chingono and Dan Rasmussen.

Valuing Private Equity Strip by Strip by Arpit Gupta and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh.

Private Equity: The Emperor Has No Clothes.

Bain Global Private Equity Report 2023.

Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look by Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan.

Stranded fossil-fuel assets translate to major losses for investors in advanced economies.

The changing role of central banks by Charles Goodhart.

Shadow Banking: The Money View by Zoltan Pozsar.

Securitization for Sustainability By Daniela Gabor.

Making the great turnaround work. Economic policy for a green and just transition.

From the Washington Consensus to the Wall Street Consensus.

Breaking the Deadlock on Climate: The Bridgetown Initiative.

Manifesto for an ecosocial energy transition from the peoples of the South.

Videos

What Do We Know About Private Equity Performance? Guest Lecture by Steve Kaplan.

Eric Johnson on Private Equity Performance and its Intricacies.

The Risk and Return of Private Equity by Arthur Korteweg.

Should You Trust Private Equity to Take Care of Your Dog?

From shadow banking to market based finance: old wine in new bottles?

Building A Private Finance System For Net Zero | Daniela Gabor

Regulating banks in the era of fintech shadow banks

Exit, control, and politics: The power of finance under asset manager capitalism

The Washington Consensus Dani Rodrik and Branko Milanovic

Josh Younger on the Origin Story of the Shadow Banking System

Younger and Menand Explain How We Got the Modern Banking System

Leave a Reply