For some reason, I’ve long been fascinated by news publishing. At one point in my life, I wanted to be a journalist. Thank God I didn’t become one. As romantic as poverty feels, I’m not a huge fan of being poor. Despite dodging that bullet, I was still enamored by the industry—I quite can’t put my finger on it as to why.

Though I didn’t end up working for a news publisher, I’ve followed the industry for well over a decade like a dedicated stalker. I’ve mourned dying publishers, cheered new startups, felt guilty about using hacks to dodge paywalls of sites whose subscriptions I couldn’t afford, and then donated some money to them to assuage my guilt.

There was a brief moment when I stopped following the industry, about 4-5 years ago, but I couldn’t ignore it for long. Late last year, I even wrote a long post about why news publishers around the world were in such deep trouble. I published the post right around the time when the new media darlings, BuzzFeed and Vice, were knocking on heaven’s door.

I’ve been ruminating more and more about the industry ever since because the constant drumbeat of negative news keeps getting louder. From the time I published the long ass post, shit’s been getting more real. The Messenger, a news site started by veteran media executives, raised $50 million and shut down in January 2024 after burning it all in 8 months.

In the same month, Condé Nast laid off key staffers at the legendary music publication Pitchfork and folded it into GQ. The Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Time, Sports Illustrated, Business Insider, and other publications laid off hundreds of employees. In India, Times Internet laid off several hundred employees.

In 2023, there were over 3,000 layoffs in the US. 2024 seems to be on track to break that record. The New Yorker and several other media observers called the latest bout of media troubles an “extinction-level event.” In 2024, people talk about news publishers with the enthusiasm and cheerfulness of funeral announcements.

After following this bloodbath over the last 6 months, I couldn’t help but wonder: are we closer than ever to a world without news?

It’s very easy to say yes given all the pessimism, but I don’t think this is a question with a yes or no answer.

In developed markets like the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, the news publishing industry resembles a wasteland. Local news has been decimated, and these outlets are being strip-mined for pennies by private equity and hedge funds. National news coverage is limited to a few sick but surviving publishers.

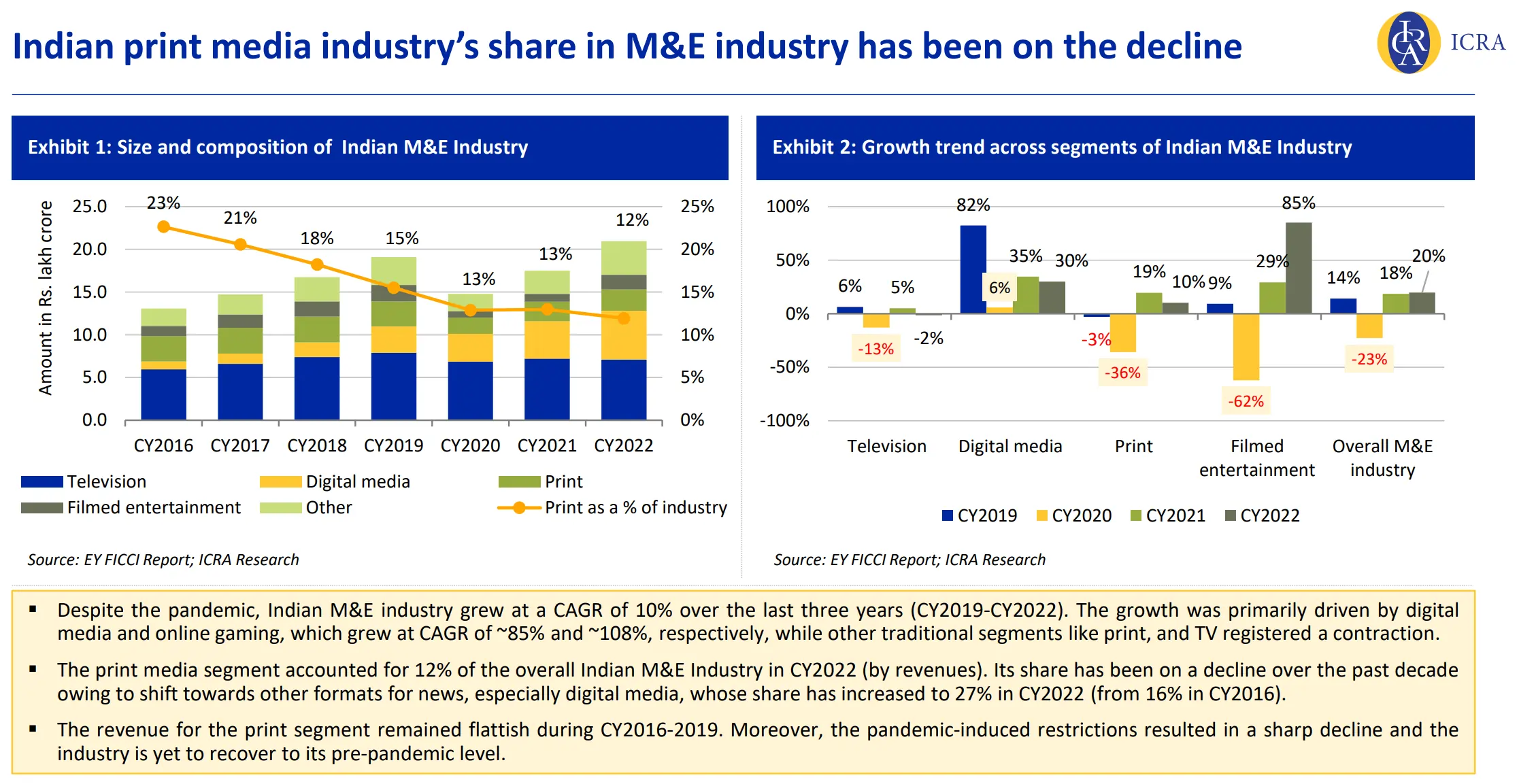

While it’s tempting to talk about India in the same breath as the US—something I’ve been guilty of—it’s not all that bad…yet. India is an outlier where newspaper circulation seems to be holding steady. It’s hard to draw definite conclusions because the circulation data sucks!

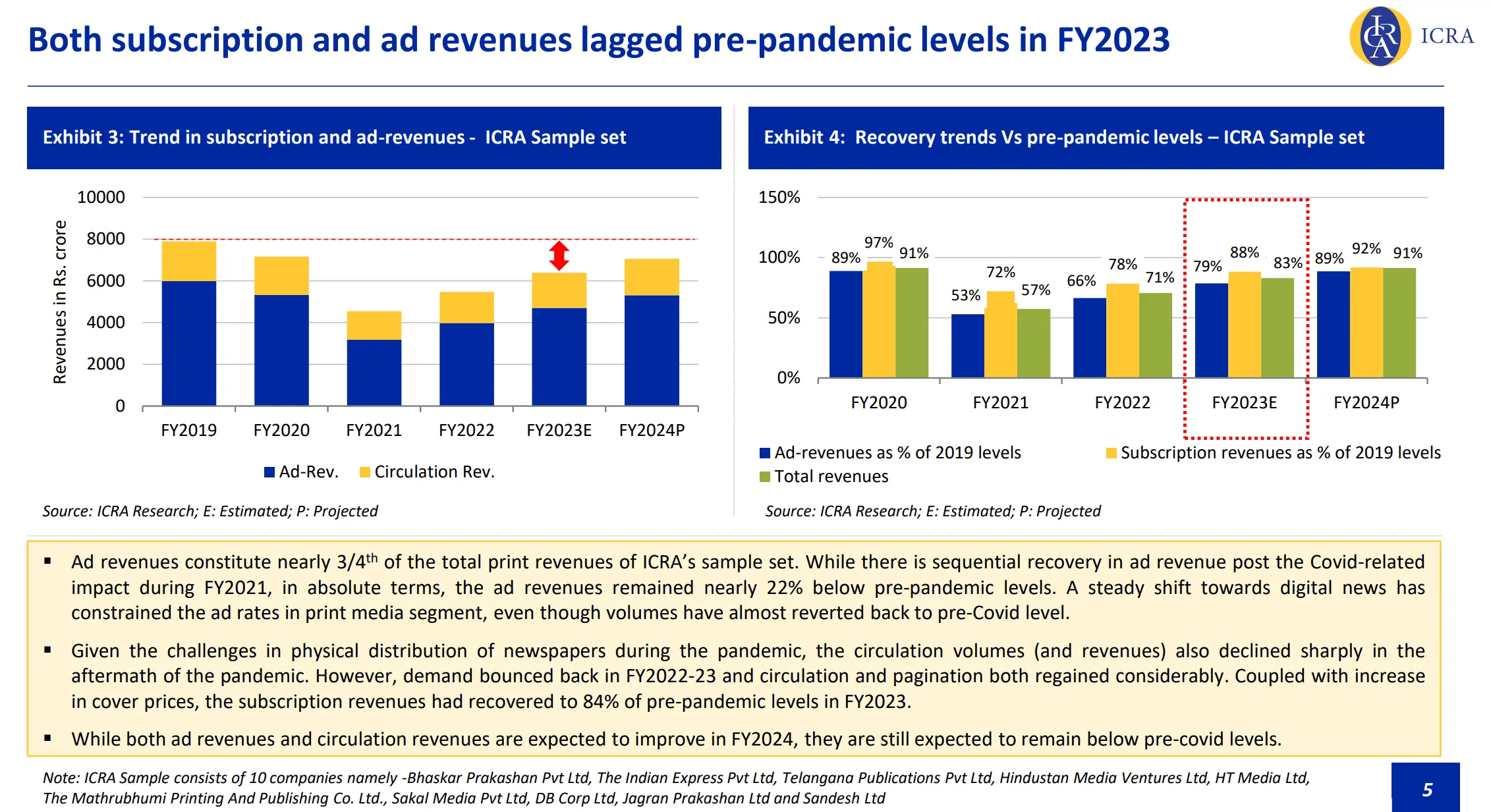

The available data shows that the print industry is growing at a slower rate compared to the overall media and entertainment industry, but growing nonetheless.

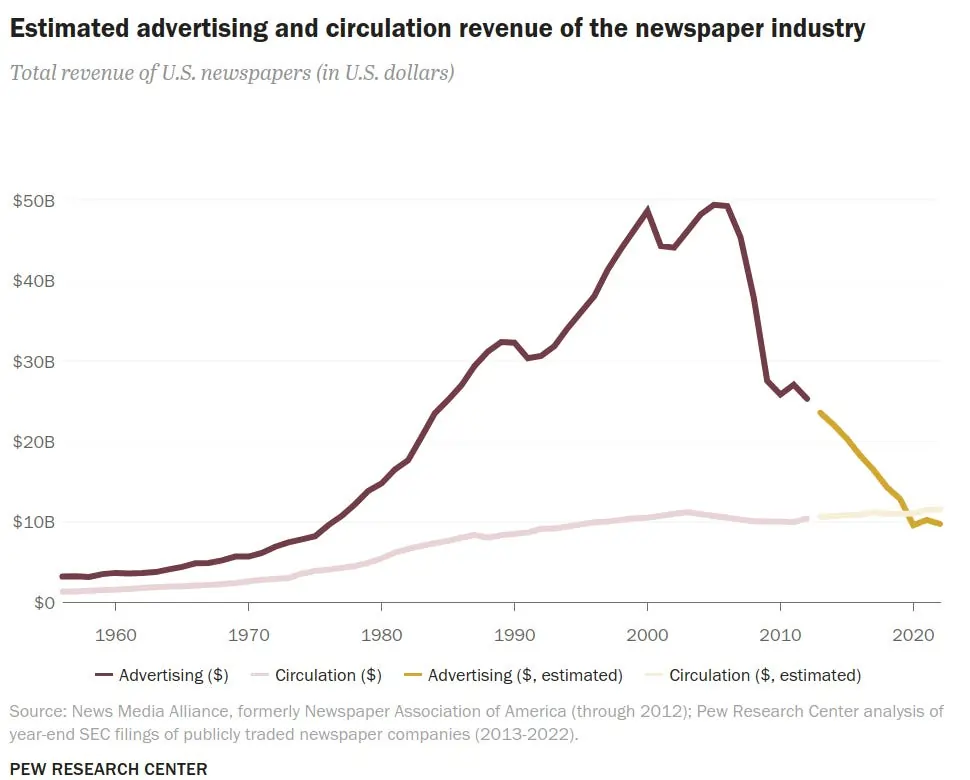

For comparison, here’s what the US newspaper industry looks like. I’m contrasting India and the US because the US news industry is in terminal decline, and the same trends could play out in India as well.

But a closer look at the numbers shows that there’s trouble around the corner. According to ICRA, print as a percentage of the media and entertainment industry has fallen from 23% in 2016 to 12% in 2022. Digital media has been the biggest beneficiary of this shift away from print.

Having read the history of US newspapers, Indian newspapers look like they are in the same position as US newspapers were before the internet. US newspaper circulation and revenues rose for a few years after the advent of the internet and then nosedived.

The story may not play out exactly as it did in the US because India is not a homogeneous market like the West. In fact, India is many small countries in one. The dynamics between English newspapers and regional newspapers are also different. The circulation of regional papers seems to be holding on far better than that of English papers. But the net effect on print will be the same as consumers move from print to digital.

Coming back to my question, are we closer than ever to a world without news?

At a local level in the US, the answer is yes, but at a national level, readers are still well served. In India, things aren’t as bad as the US, but you can see the signs of trouble.

But as a thought experiment, let’s assume there was no print or digital news. What would such a world look like?

Tin-pot republic

Democracy would choke and gag in the darkness as it’s slowly BDSM’d to death. We’d watch this spectacle on shorts and reels with catchy Bollywood background music. Nobody would agree on anything, and we’d all have our own special versions of the truth.

Our world would look something like a version of the movie Idiocracy—the greatest movie ever made. It’s a parody set in the year 2505. Joe Bauers, played by Luke Wilson, signs up for a secret army experiment that goes wrong. He wakes up 500 years in the future in a world that has become spectacularly dumb.

The president of the United States is a wrestler and a porn star. The economy has cratered, and cities have become dust bowls with mountains of garbage everywhere. People live on junk food and entertain themselves by watching shows with titles like “Ow! My Balls!” The US is also facing a famine because they water the crops with an energy drink called “Brawndo.” People have become so dumb that all it takes to become the smartest person in the world is to identify basic shapes and answer questions like 2+5.

A world without news would look similar. It has become fashionable to say that the news is useless. There’s some truth to it. Not everything that news organizations publish is useful. In fact, most of it isn’t. But on their best day, news is the disinfectant of a democracy, just like a good financial press is for the markets. I still believe in this romantic notion.

Of course, it goes without saying that news publishers aren’t always good at their jobs. Half the reason people don’t trust the news is because of self-inflicted wounds.

Massaged news

Indian media is more concentrated than it ever was. Many of the major outlets are now owned by billionaires. Mukesh Ambani owns Network18, which owns properties like CNBC, CNN-News18, Moneycontrol, and Firstpost. Gautam Adani now owns NDTV, Quint, and IANS.

This isn’t just an Indian phenomenon. Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post, Laurene Powell Jobs owns The Atlantic, Marc Benioff owns Time, and there are plenty of other examples. As much as we romanticize the idea of a benevolent billionaire, rich people owning media is not without issues. Anyone who thinks otherwise is deluded. Media companies have to dance to the tunes of their masters—that’s the price of not going out of business.

As tragic as it sounds, I’d rather have a news outlet owned by a billionaire than a bankrupt one. That’s how bad the news business is.

But in a world without newspapers, billionaires wouldn’t have to worry about being seen. The news companies they own would become their PR arms and happily churn out their propaganda and nonsense on an industrial scale. News companies would exist only to make their masters richer and powerful.

Loudmouths

Singam Abswala would be the most famous news anchor in the country, with the most watched news show streamed live on YouTube. Lies would be the truth, and parody would be reality. In fact, we’d no longer have lies, just alternative facts. Ricky Gervais saw the future.

A world without news is not good.

How do you save news?

The business model of news that worked for the last 200 years is incompatible with the digital age. Today, over 70% of the cost of a newspaper is printing and selling the paper. As print declines, these fixed costs become a noose. This is why print is no longer viable in developed countries, and it will eventually become unsustainable in India as well.

Before the internet, American newspapers also enjoyed the privileged position of being the gatekeepers between readers and advertisers. Advertisers subsidized the news as long as newspapers were the only way to reach consumers. The internet flipped this model. Consumers and advertisers had more choices than ever and newspapers lost their gatekeeping privileges.

Advertisers abandoned print for digital advertising because advertising platforms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon offer far superior targeting capabilities than a dumb print ad. A similar but nascent shift is underway in India. Print advertising is still big but won’t be forever.

As print advertising fell, US newspapers couldn’t replace the lost dollars with digital revenues. Digital advertising revenues were a drop in the bucket. There was a saying that newspapers were trading “print dollars for digital cents.” This seems to be the case so far in India as well. Digital advertising dollars will always be a fraction of print advertising.

The number of Indians who pay for digital news subscriptions is peanuts. I could be wrong, but people think of a newspaper subscription as a separate item in their budgets. But people think about a digital news subscription in the same vein as Netflix and Spotify. They choose one over the other.

The post-COVID recovery in print was much slower for English papers than for regional languages in India. That’s a sign that something is changing. It could be that English news readers in India are choosing digital instead of print. It could also be that people have stopped their news subscriptions for Netflix due to inflation. This has been the case in developed countries.

So, what works?

As an amateur observer of the news industry, here are my thoughts:

Advertising

It’s impossible for newspapers to offer the same advertising propositions as Google and Facebook—publishers don’t have the tech chops. So it’s guaranteed that print advertising will continue to fall. But it’s not impossible to pivot. Publishers like The Independent have shown that you can kill your printing operation and still thrive.__

End of mass delusion

The era of chasing scale, aggregating attention, and then selling it to advertisers is over. It worked for a brief moment in time because of the generosity of social media platforms, but all that’s over. Social platforms are now deliberately throttling external links. They don’t want people to leave their websites and apps. All the publishers that relied on social traffic are dead.

Subscriptions

That Indians don’t pay for stuff has become accepted wisdom but I disagree a little. They pay if they see value. There are several independent subscription based publishers like The Ken, Newslaundry, The News Minute, and The Morning Context that seem to be doing okay. Other publishers like The Wire, The Print, Scroll, and Reporters Collective rely on donations, and they seem to be surviving.

All traditional publishers offer digital subscriptions, but this subscription base is still small. This is partly because most of them have shitty offerings. I consume finance news the most, and the quality of what traditional publishers like Mint and ET produce is horrendous. Even in general news, you can see the deterioration in quality.

Having said that, we’re still a low-income country, and the pool of paying users is small. This will grow if our economy does well.

Small is beautiful

Money from subscriptions will never offset print revenues. This is why I think that the era of mass publishing is over. Most of the large traditional publishers will either shrivel or die, and we’ll be left with a few large national publishers.

The future of news will be small and focused. The large traditional publishers will never be able to maintain quality across all verticals. In the coming decade, my bet is that we’ll see small and focused Indian publications across niches like business, culture, women, health, climate, mental health, and tech.

Building such publications will be a blood sport. The problem with applying a US lens to Indian media is that some people forget we are a poor country. Few Indians can afford the luxury of paying for news subscriptions, but the numbers will grow over time. Small publications will never rake in a boatload of cash, but the journos will be able to feed themselves.

Media companies will do well to learn from individual creators. Channels like Think School, Dhruv Rathee, etc. Thy make more money from YouTube and sponsorships than most small news publishers. A lot of traditional journalists look down on creators. Of course, some deserve to be looked down on because they are idiots. But there are some savvy creators like Mike Solana who are building their own small media empires.

The typical uppity attitude of media companies and journalists is a liability, and it will be their undoing.

Billionaires

Billionaires are starting to regret their media purchases. The Washington Post lost $100 million last year and is at a crossroads. Marc Benioff, who owns Time magazine, laid off 30 people. The Los Angeles Times, owned by billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, laid off 115 people. There’s no shortage of cautionary tales of billionaires trying to save media, but they believe this time is always different.

My bet is that the rich people will cut their losses sooner or later, and these storied publishers will be back to square one. Media rarely has happy endings. It’s either less horrible or more horrible.

Independents and collectives

A few years ago, traditional news publications in the US had a mild case of Substack panic. For a minute, it seemed that all star reporters would leave to start their own paid newsletters. There were some success stories, like Casey Newton and Matt Yglesias, but the trend seems to have died down. Reporters leaving to go solo isn’t a thing in India, barring a few like Ravish Kumar and Barkha Dutt. I wouldn’t be surprised if this trend picks up in India over the next five years.

Collectives are a new model that I’m excited about. Sick and tired of precarious employment situations, journalists are banding together to form collectives or cooperatives. The writers own the collective and operate it like a media company. This ensures that the incentives are aligned in the right way. Several collectives, like Defector, Hell Gate, and Flaming Hydra, have popped up on the scene.

I don’t think there are many journalist collectives in India apart from Khabar Lahariya.

Age of the individuals

An extension of this trend of collectives is that we may be entering a golden age of individuals. There’s truth to the annoying quip that “people trust people.” For over 200 years, publishers hired a bunch of writers, put them in a room, and published a news bundle. This model no longer works.

One of the most exciting trends in media has been the rise of individual experts, creators, curators, influencers, or whatever you wanna call them. You see this most prominently on Substack. There are brilliant individual newsletters on everything from technology, philosophy, history, and construction to physics. Before the Internet, a few of these people had blogs, but they were largely invisible. But thanks to platforms like Substack, WordPress, Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube, individuals are publishing far more insightful things than journalists.

The next big media company will be an individual newsletter, blog, podcast, and YouTube channel. News publishers will need a new playbook for this era because these individuals won’t work in the stifling environment of a newsroom. Opinion pages are a halfway solution because they no longer signal the same credibility that they used to.

Die tomorrow

When you’re drowning, you’ll clutch at anything, including straws. One such straw for news publishers was forcing tech companies like Google and Facebook to pay for news. Australia, Europe, and Canada passed bills that forced tech companies to pay publishers for allowing news on their platforms.

After some protest, both Google and Facebook started paying publishers in Australia. But last month, Facebook announced that it would stop paying. Facebook also blocked the sharing of news links in response to a similar bill in Canada. Google, however, struck a deal to pay Canadian publishers.

Forcing these companies to pay for the right to send traffic to news publishers was always a stupid idea. The regulations are based on the flawed notion that internet companies destroyed news, but that’s a lie.

News publishers are also cutting deals with AI companies to allow them to use news content to train models. OpenAI is reportedly offering between $1 million and $5 million a year to license news articles from publishers. Axel Springer, which owns Business Insider and Politico, and Associated Press are major publishers that have cut deals.

The sad reality is that none of these things can fix the fundamental flaws at the heart of news publishing.

Public funding

The day isn’t far off when governments may be forced to fund public-service media. The BBC is the gold standard for such a model but there are other examples in Europe and Canada. This is a fringe idea in the US because of the general wariness of big government, but it’s an idea that I am sympathetic to.

Government involvement in media comes with its own issues, but it’s better than having no media at all. At some point, people have to realize that free markets aren’t the answer to everything.

Throw the kitchen sink

In a 2009 essay, media guru Clay Shirky has a memorable line:

The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might. Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments, each of which will seem as minor at launch as craigslist did, as Wikipedia did, as octavo volumes did.

It’s very hard, if not impossible for the media company of the future to survive and thrive on just one revenue line. Successful media companies such as The New York Times (NYT), The Economist, Financial Times (FT), and Condé Nast have their diversified revenue sources to thank for their survival.

In the case of NYT, it’s subscriptions and print, but the company has built a phenomenal bundle that includes news, games, audio, commerce, and cooking. The Economist generates revenues from subscriptions, courses, and research services.

The FT generates revenues from subscriptions, consulting, events, and recently launched a venture investing arm. Building diversified revenue streams is an existential imperative for media companies. Condé Nast generates over 40% of its revenues from subscriptions and commerce. I think it’s possible to generate revenue streams by solving the problems of audiences.

Innovation

I hate using this word, but bear with me. Quality in media is table stakes; it’s the least that publishers have to ensure to be even considered by readers. But it isn’t enough to ensure survival.

Traditional media companies still operate like factories. They manufacture information and dump it on a website, expecting people to discover and pay for it without any consideration for what the readers want.

I was listening to Anant Goenka, the Executive Director of The Indian Express Group, on a podcast, and he said something that was stunning to me:

Ananth Goenka: I think one of the big wins, and it’s tough to kind of say, but since it’s a long conversation, we can get deep into things. I remember I had a session with my chief editor, my father, my CEO, and a bunch of us, kind of just four or five of us, sat down. I was just kind of saying that somewhere, the consumer, the reader, is not central to our decision making as a content producer. Somewhere, I mean, the user wants to talk about climate change, artificial intelligence, mental health, gender issues, and the taboos with being sexually experimental. That’s kind of where the English-speaking, urban, Express profile reader is.

However, we’re kind of, in a sense, still trying to make them read about our politics, which is great and a super thing, but we’re also trying to make them read about over-investing resources and covering, you know, that bus accident in a random rural part of India. These are all important to uncover, but somewhere we’re not addressing these needs, and some people are kind of missing this, missing them.

Even if we do address their needs and even if we do get the content that we want to get them, we’re not quite able to consistently engage with that user base enough for them to recognize that, hey, in this crowded market of one lakh registered newspapers and 500 news channels, there is one Indian Express which is consistently giving me high-quality, credible news and information on climate change. That hasn’t yet happened.

The reason it hasn’t happened is because we’re not really thinking about the consumer.

The fact that media executives have to say this out loud is tragic. The old-school model of manufacturing content to maximize advertising inventory is over. It won’t work, partly because few media companies have invested in building first-party data and good ad products. Most of them rely on programmatic advertising, which generates peanuts.

At a national and international level, US media consumers are still overserved. The brutal competition has forced publishers to innovate a little in terms of coverage, formats, and voice, but that’s yet to happen in India.

When it comes to serving the affluent urban Indians that can pay, Indian media companies have done a piss poor job. Can you think of a decent daily newsletter, a podcast, or a video series that you look forward to from an Indian publisher?

I can’t.

With very few exceptions, they all suck.

Daily newsletters and podcasts are habit-building products. If they are good, users look forward to them. This is why The Daily by The New York Times and The Intelligence by The Economist have been so successful. Both publishers also have an amazing bouquet of newsletters.

The Economist also launched an app-based digital edition at a cheaper price to attract younger audiences. Even the Financial Times launched a similar app aimed at social followers who hadn’t yet subscribed to anything. The Vox is another success story. They moved fast to build a brilliant stable of podcasts.

It’s a tragedy that Indian media companies have ignored white spaces that require minimal investment, like newsletters, podcasts, and curated products aimed at younger audiences.

Curators

In a 2007 blog post, the famous media guru Jeff Jarvis wrote, “Cover what you do best. Link to the rest.” 17 years later, I think this is brilliant advice. Every media company tries to rehash the same news story in 100 different ways, and that’s a waste of resources. They do it because of SEO imperatives, but AI might make SEO less relevant.

Publishers have a golden opportunity to specialize in a few areas and then become aggregators for the rest. The problem is that this is an unnatural way of thinking, but publishers have always been aggregators. Opinion pages are an example of it. I think there’s a brilliant opportunity for a new media company that is both a creator and a curator. The new CEO of The Washington Post said as much recently:

So you’re looking to go to make the Post’s footprint bigger, not to drill into smaller Washington lanes?

One of the many things we’re blessed with is that we’re probably one of the few mastheads in America that can help other news organizations and can think about aggregation. The fundamental challenge for the news industry is how, how do you deliver ever more specific verticals — people really, really want to know about the widget industry, but there’s only 1000 of them. How do I charge them enough? This is the fundamental challenge we’re facing and no one’s cracked it yet. We can play at an aggregation level.

Artificial intelligence

My default frame of thinking about artificial intelligence is that it’s going to disrupt a lot of things, especially the media. In fact, it’s safe to assume that the information economy will never be the same.

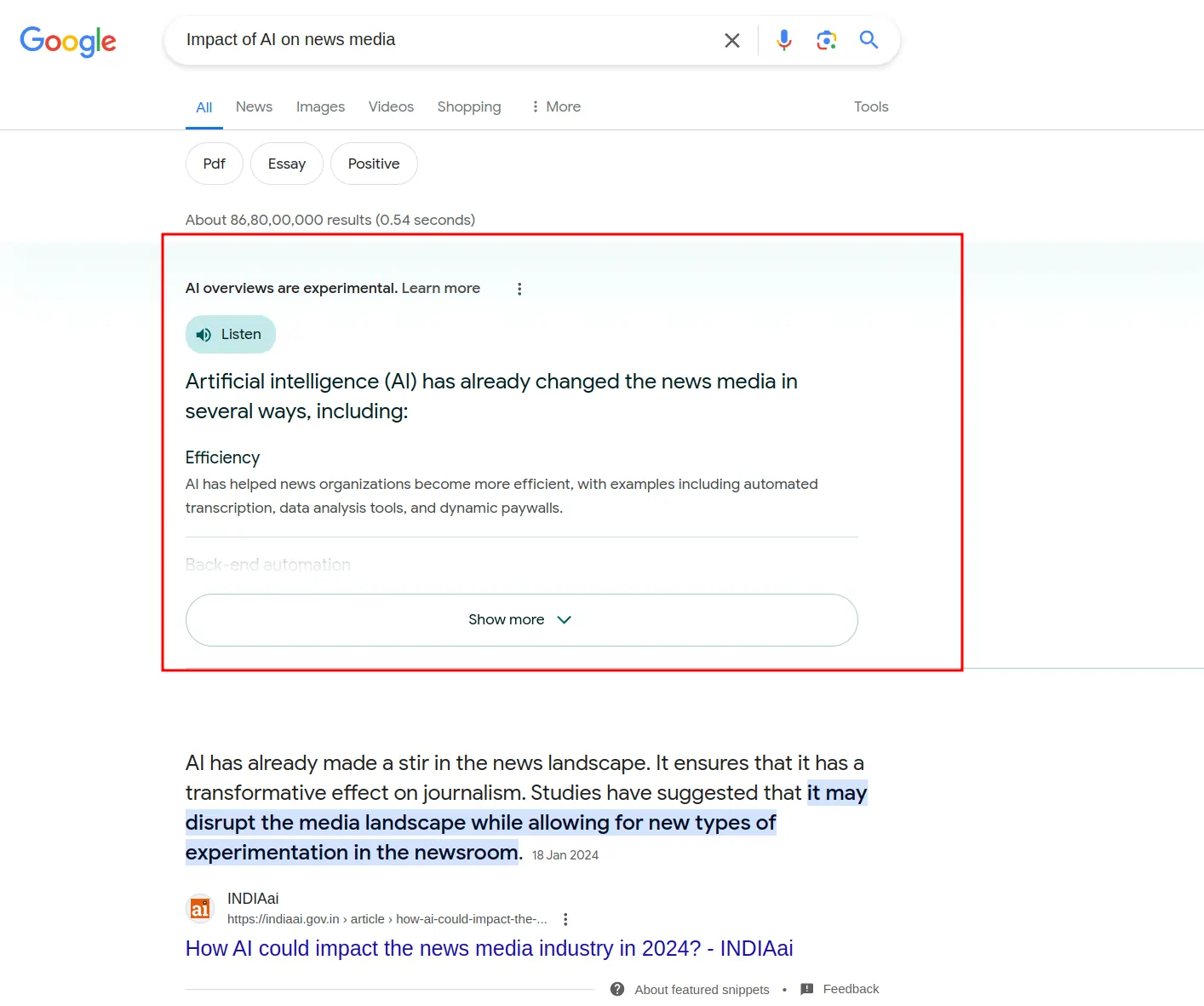

While fewer people visit the homepages of news publishers, a sizable audience still does. Imagine having an app where you can ask anything you want. Would you still visit websites, scroll, search, and discover information? Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Claude are doing just that.

With LLMs, everybody on the planet has access to the collective knowledge of humanity at their fingertips. All they have to do is type into a chat box. The way we search for information will never be the same. I’ve been using ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Claude, and my Googling has reduced quite a bit.

Then there’s Google’s own Search Generative Experience (SGE). Whenever you Google something, you’ll see a box with AI-powered summaries. Now that social referral traffic has all but vanished, Google is once again the dominant source of referral traffic. If Google starts showing AI summaries instead of just links, publishers will be affected.

The bigger question is: what will happen to media brands if people start getting their news and information from a chat box? AI enables everyone to build their own curated and personalized news streams. Perplexity’s AI-powered daily podcast is a sign of things to come.

Trust

Trust is the currency of the news business. People will always bitch and moan about “mainstream media” and “Lutyens Media,” but when push comes to shove, they’ll always come running to the same sites. You saw this during COVID-19. Legacy news sites experienced massive traffic bumps because people preferred journalists over that the guy who used to tweet that donkey urine and pouring citrus juice in one’s ass cured COVID.

It’s going to get harder for news publishers to build trust because of coordinated attempts by the left and the right to discredit news. But if publishers don’t cower, readers will take notice. Some readers might be idiots, but not all are. They deserve far more credit than they get.

Trust is going to become even more important as the tsunami of AI-generated crap gets bigger. It’s still early days, and Google is already swamped with AI-generated bullshit, and it’ll only get worse. In such an environment, publishers have a golden opportunity to stand out as trusted voices.

What do you think?