The relative calm of 2021 feels like yesterday to me. Sure, we had a virus that was hellbent on killing us, but most of us had made peace with our impending deaths. After a while, the biggest worry for most people was getting caught on a video call wearing a suit without pants. Good times. But in a span of months, we went from worrying about partial nakedness to losing sleep over whether we’re headed for a great depression style 90% stock market crash.

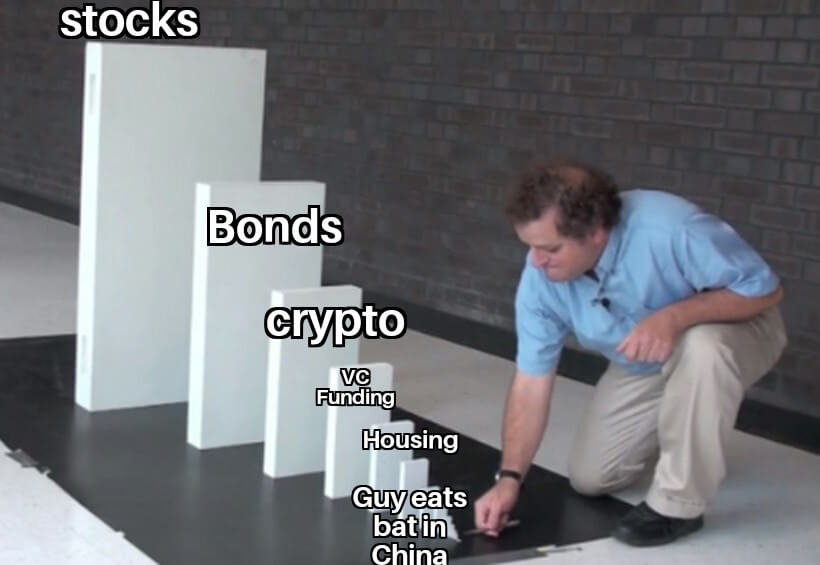

Until last year, everybody was a stock market genius. You couldn’t make a bad trade even if you tried. Even the most idiotic trades seemed like a stroke of genius. But since the start of 2022, people are back to looking like idiots again. Stocks, bonds, bitcoins, shitcoins, real estate, venture funding, private equity deals, IPOs, SPACs—everything is down, there’s no place to hide. Actually, that’s not true, you could hide in cash, but learned men have proclaimed cash is trash.

It also feels like a Minsky moment. All the Ponzi-like activities and business models that relied on prices going up, ever more speculation and a steady inflow of suckers are unraveling spectacularly. The blow-ups are not just in crypto but, in stocks and bonds as well.

November 2021: We’re going to the moon.

May 2021: We’re going to hell.

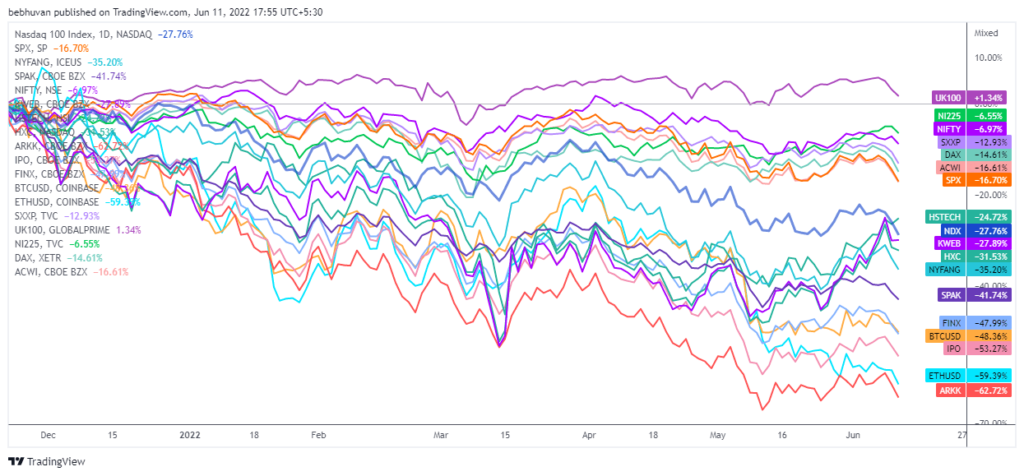

It’s stunning how the sentiment changed from absolute joy to despair in a matter of months. Unlike the 2020 crash, the current market fall feels different. It looks like we’re in the midst of a regime shift in the market—I don’t know what this means. I always wanted to use “regime shift” in a sentence.

The markets, especially the US, are looking bad right now. All the craziness and the frothiness of the past 2 to 3 years have disappeared in the span of weeks. Just a brief spike in inflation (hopefully) was enough for the markets to fall like dominoes.

What’s happening? How did we get here? What happens to stonks from here on? Are we still going to the moon?

Here are some long, incomplete and utterly unsatisfying answers.

Do you remember the opening monologue of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy narrated by Stephen Fry? It’s one of my favourites.

It’s an important and popular fact that things are not always what they seem. For instance, on the planet Earth, Man had always assumed that he was the most intelligent species occupying the planet, instead of the *third* most intelligent. The second most intelligent creatures were of course dolphins who, curiously enough, had long known of the impending destruction of the planet earth. They had made many attempts to alert mankind to the danger, but most of their communications were misinterpreted as amusing attempts to punch footballs or whistle for titbits. So they eventually decided they would leave earth by their own means. The last ever dolphin message was misinterpreted as a surprisingly sophisticated attempt to do a double backward somersault through a hoop while whistling the star-spangled banner, but in fact the message was this: So long and thanks for all the fish.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

In the monologue, replace the dolphin with all the sane people who warned investors not to go crazy, and the man with traders and investors who ignored the same people and YOLO’d into penny stocks and weekly call options. Now, replay the monologue in your head, and it perfectly sums up the last decade and a half in the markets—especially the post-pandemic years.

So, what’s happening?

To understand this semi-extraordinary moment we’re living through, we must go back to 2008. Remember 2008? Of course, you don’t! It was the year in which the entire global financial system almost ended. Apart from that, it was pretty uneventful. Even before the COVID-19 shock, very few people remembered 2008, but now it’s an afterthought.

Remember the opening monologue of The Lord of the Rings? I think it was a documentary about the 2008 financial crisis.

And some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend. Legend became myth. And for two and a half thousand years, the ring passed out of all knowledge.

The Lord of the Rings

It’s been 14 years, but the ghosts of 2008 still haunt us. It might be availability bias since 2008 was the first crisis of my lifetime. But the roots of all the major issues we face today either originate in or pass through 2008. The crisis also marked a tipping point that permanently changed the trajectory of the 21st century, and not in a good way.

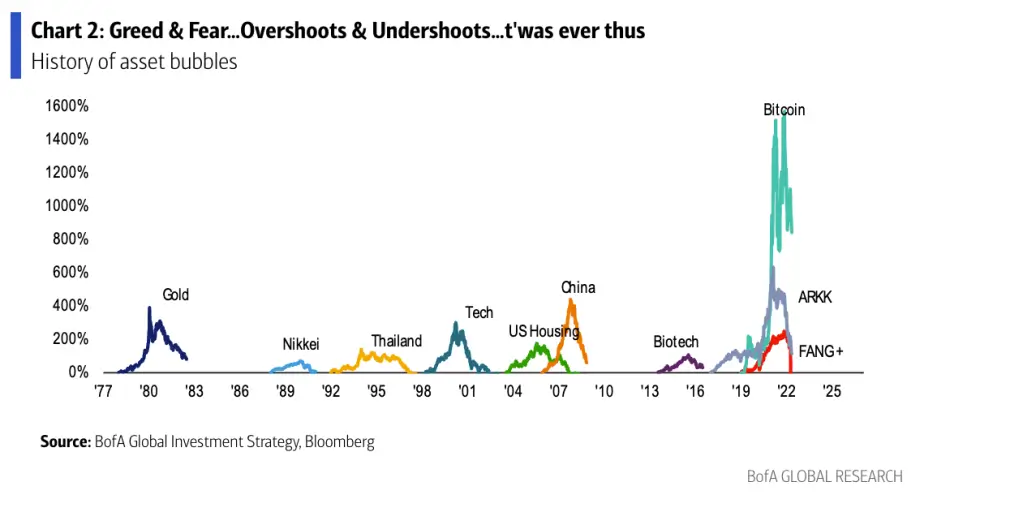

I think it’s important to look back at past crises once in a while. Even though Mark Twain never said, “History Doesn’t Repeat Itself, but It Often Rhymes”, he wasn’t wrong. If you think today’s markets are uniquely crazy, they aren’t. You could see the same sort of craziness back in 2008, although in different segments. The more you read about financial crises, the more apparent it becomes that, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Here’s a 10,000-foot view of how we ended up where we are. As you read through, you’ll see several recurring themes and behaviours. By the end, you’ll realize that human stupidity is terribly unoriginal.

Seeds of a crisis

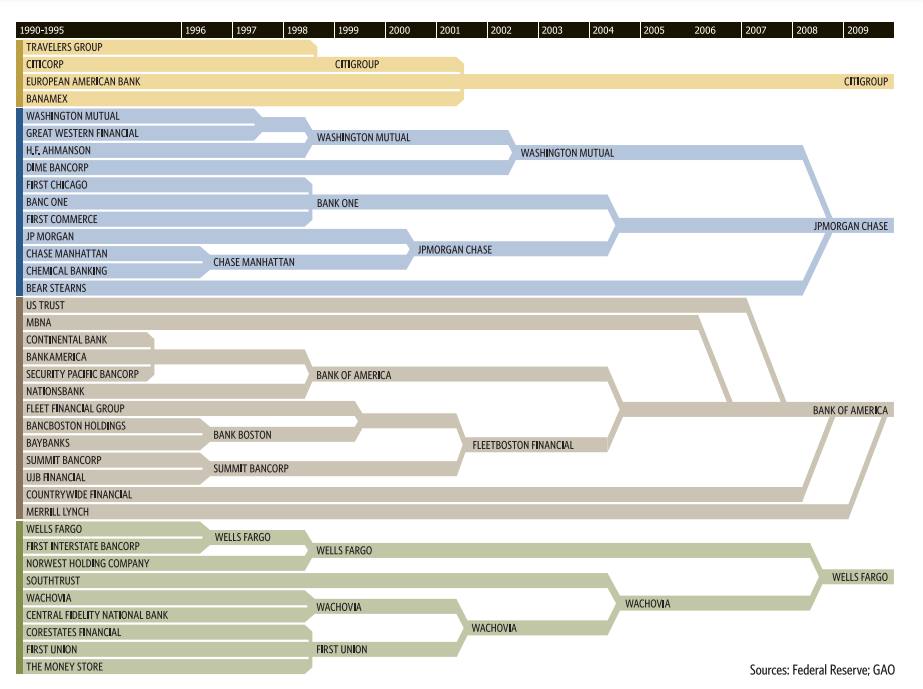

The popular narrative of the 2008 crisis is that it was just a housing crisis in the US. But that’s an incomplete view at best. 2008 was a full-blown global shadow banking crisis, and the housing crash was just the trigger. Shadow banks are non-bank entities like money market funds that function similar to banks. The roots of the 2008 US housing crash can be traced all the way back to the 1960s, but most of the developments that would cause the crisis were in the 1980s and 90s.

US commercial banks were facing an existential crisis in the 90s. They were just recovering from the savings and loan crisis and were losing deposits to money market mutual funds because they offered better yields. Their mortgage businesses were also under siege. The 80s and 90s were also a fertile period for financial engineering. This was the period during which securitization structures like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and financial insurance like credit default swaps (CDS) became popular. At the same time, shadow banking entities like money market funds and repo had grown substantially and had become large sources of funding for financial institutions.

Commercial banks typically sold off the mortgages they originated to government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. As securitization grew, banks saw they could generate lucrative fee revenues, but regulations didn’t allow these banks to get in on this action. Luckily, the Clinton administration under Robert Rubin and Larry Summers heavily deregulated Wall Street in the 90s. In the aftermath, commercial banks quickly became vertically integrated mortgage producers. They were involved in everything from origination and securitization to investing in Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO) on their balance sheets.

Investment banks like Goldman Sachs and Bear Sterns were scrappy outfits, and they couldn’t grow as fast as they would’ve liked due to regulatory constraints and the lack of cheap funding like deposits. But thanks to the rise of money market funds, they now had a cheap funding source. With securitization, they could repackage risk, and with CDS, they could insure it. Deregulation was the final piece of the puzzle and gave them the license to enter new businesses and unleashed a spectacular wave of consolidation. Investment banks quickly got in on the action and became dominant actors in mortgage origination, securitization and trading.

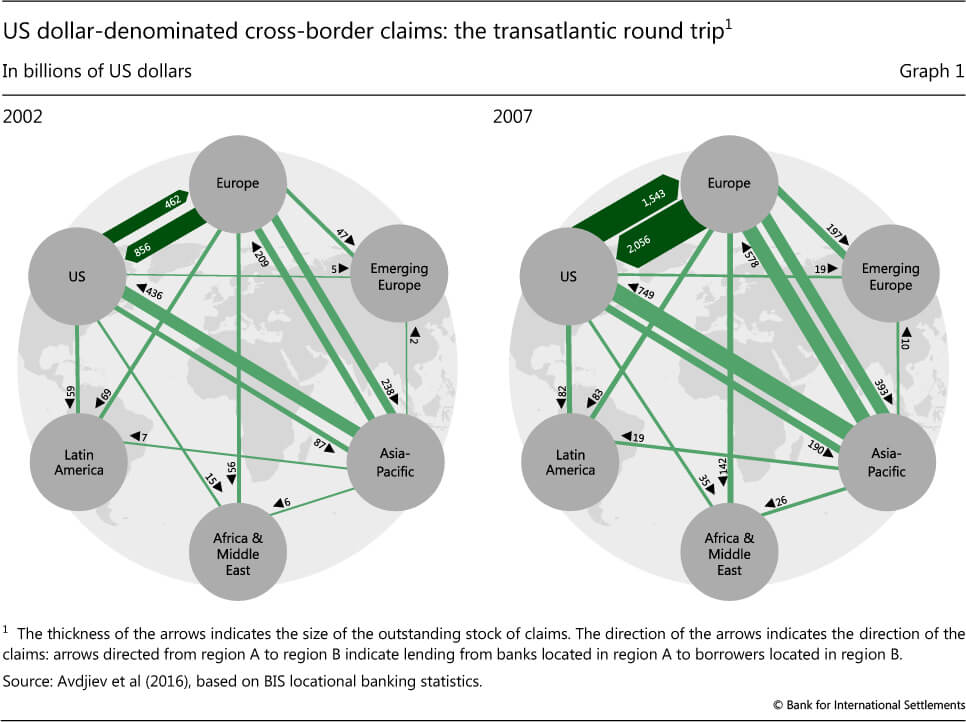

Investment banks tapped short-term funding in wholesale money markets like money market funds and repo markets to fund their securitization businesses. These loans ranged from overnight in the case of repurchase agreements (repo) to a few days to months in the case of commercial papers sold to money market funds. It was classic maturity transformation—borrow short term and lend long term. Eventually, European banks wanted a piece of the action, and they quickly became dominant players in the securitization business by setting up US affiliates.

US housing prices were booming, and European and US banks were generating massive fee revenues from securitization. Things were looking good for the big banks. But by 2005-2006, the banks had become greedy and had lent heavily to home borrowers with poor credit scores. Housing prices started falling slowly around 2006, and by 2007, the fall was severe enough to trigger housing loan defaults among the riskiest borrowers. Suddenly, all the MBS’ and CDOs that the banks were holding became illiquid and the riskiest tranches worthless. Banks were raising short-term funding by using these securities as collateral. As the lenders in the wholesale funding markets such as money market funds sensed trouble, they dumped bank-issued commercial paper and fled. Repo markets froze as institutions started hoarding good collateral like US treasuries.

Wholesale funding markets froze, and banks couldn’t borrow to service their liabilities. In a traditional bank run, depositors rush to withdraw their deposits, but 2008 was a bank run on the wholesale funding markets—money markets, repo, interbank lending and prime broking. It started in the money markets and then spread to the entire global financial system as US and European banks could not roll over their short-term debt. It’s this run on the repo markets that made the crisis so devastating. Given that banks had low equity cushions and an astonishing amount of leverage, even a tiny fall in housing prices and the vanishing of short-term funding markets were enough to turn them insolvent.

It turned out that the European banks were just as big players in the securitization business as the US banks. Their local branches were borrowing heavily in US money markets to produce mortgage-backed securities on an industrial scale.

Given the high returns, they were also holding a significant chunk of the riskiest tranches of MBS on their balance sheets. As the money markets froze, European banks could not roll over their debt and had to resort to fire sales of their best assets to fund liabilities. The dollar funding gap ran into trillions, and this rippled out through the European banking system. As John Cochrane and Adam Tooze have pointed out, people lost more money in the dot-com crash compared to the losses from the decline in housing prices in 2008. The fall in housing prices, on its own, wasn’t enough to cause a global financial crisis. The complete disappearance of wholesale funding markets made the crisis so destructive.

With the deregulation of financial markets in the 1990s, regulators assumed that the markets would reward good firms and punish the bad, ensuring everything was hunky-dory. This irrational belief in free markets was best summed up by former Fed chair Alan Greenspan’s reply when asked who he was supporting in the 2007 election:

We are fortunate that, thanks to globalisation, policy decisions in the US have been largely replaced by global market forces,” he replied of the contest between Barack Obama and John McCain. “National security aside, it hardly makes any difference who will be the next president. The world is governed by market forces.

Alan GreenSpan

But the regulators couldn’t have been more wrong. Even as a thought exercise, it’s hard to imagine what would’ve happened if the biggest banks and financial institutions weren’t bailed out in 2008.

The US and Europe were the epicenters of the crisis, but the crisis rippled out across the world. Economies around the world contracted, global trade shrank dramatically, consumer spending collapsed, and confidence cratered. The advanced economies were on the verge of going back to the dark ages.

The 2008 crisis also exposed the deep-rooted problems in the structure of the Eurozone. The tranquility of the pre-2008 crisis period masked the structural and economic imbalances. But the severity of the 2008 crisis brought them to the fore all at once and triggered the Eurozone crisis. The credit-fuelled housing bubbles in the UK, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland imploded spectacularly. This also triggered the sovereign debt crisis in Greece, which already had substantial levels of hidden debt. The policymakers in the US got their act together relatively quickly and took dramatic measures to stop the imminent implosion of the financial system, but the Europeans bungled the response. Their infighting and myopic economic thinking almost ripped apart the European Union.

In response to the crisis, technocratic central bankers transformed into mad monetary scientists. They turned the entire global economy into a laboratory for unconventional monetary policies to save the global economy that was teetering on the edge of oblivion. It started with slashing interest rates to zero, and the Europeans even took it to negative. Then came multiple rounds of asset purchases, quantitative easing in the US and Europe, and all the other efforts to generate growth and inflation.

14 years after the 2008 crisis, it’s very easy to forget just how terrifying the crisis was. Perhaps nothing captures the severity of 2008 as this statement at the depth of the crisis by Ben Bernanke, the Fed chair, when asking Congress for a bailout fund for the banks:

If we don’t do this tomorrow, we won’t have an economy on Monday.

Ben Bernanke

In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, there’s a scene where Minerva McGonagall calls her unruly students a “babbling bumbling band of baboons.” That perfectly describes the European response to the 2008 and Eurozone crises. As the crisis dragged on, European financial markets were under severe stress. They needed their own Bernanke moment to calm the markets and restore confidence. Enter Mario Draghi, A.K.A. Super Mario, the ECB president. This is what he said at a conference in London:

“Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

Mario Draghi

This marked a turning point in the Eurozone crisis saga. The advanced economies stumbled their way through the 2008 crisis.

One key story that most people don’t know is that China unleashed massive fiscal spending as the global financial system was imploding. It is this gigantic stimulus that was responsible for softening the blow of the 2008 crisis. Without the Chinese stimulus, the world would’ve been a much different. The scale of this stimulus spending can be seen in the fact that China has accounted for over 30-40% of world GDP since 2008.

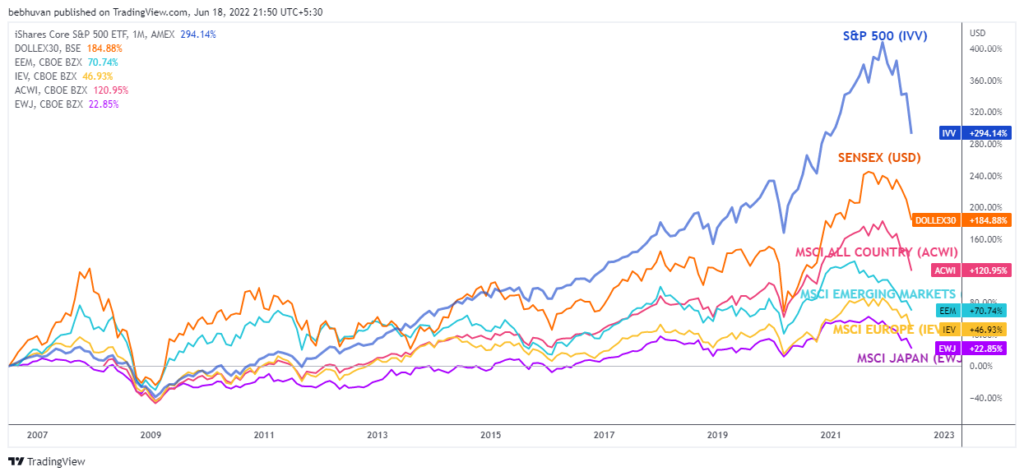

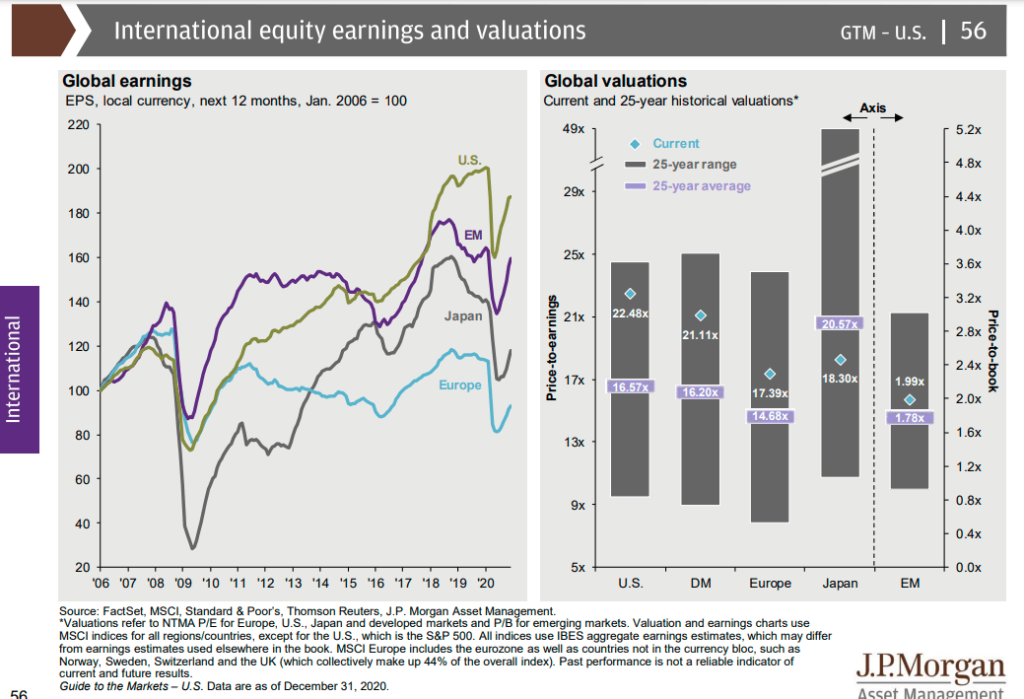

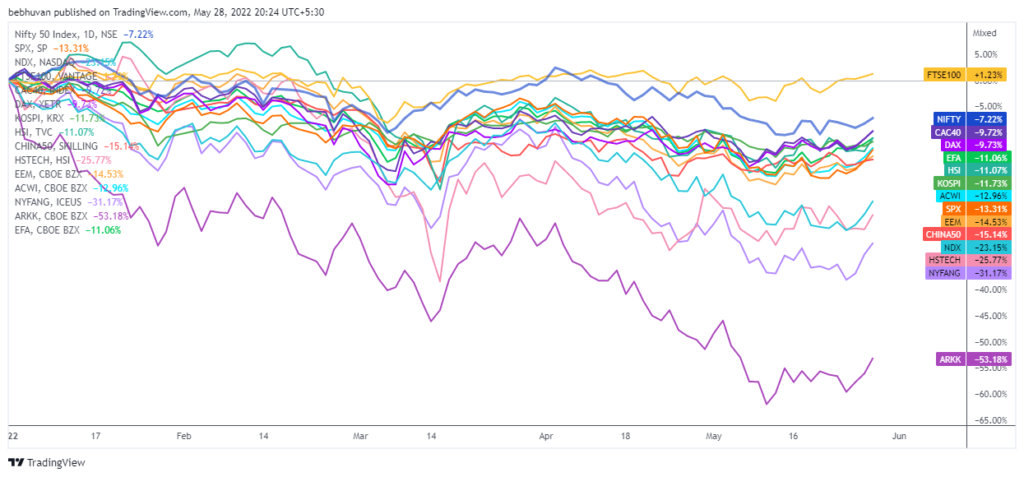

But much like the post-pandemic period, there was uneven economic recovery. Emerging and developing economies, particularly commodity exporters, recovered the fastest, while European growth flatlined. The US didn’t grow as fast as some emerging markets, but it still saw a decent recovery compared to Europe. The stock markets too mirrored the uneven recovery. The US has been the undisputed king since 2010, while much of the world had unsuccessfully played catch-up.

Narrative violation

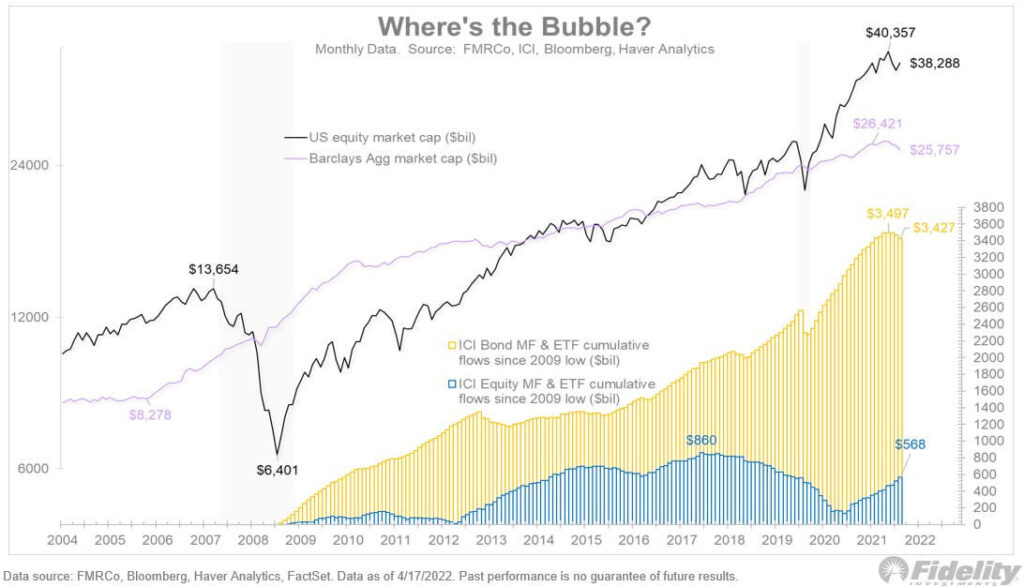

Of course, this chart poses a problem to everyone saying that we’re in the mother of all bubbles. It’s a good opportunity to bust some myths and clarify others.

Narrative #1: The Federal Reserve is creating a stock market bubble

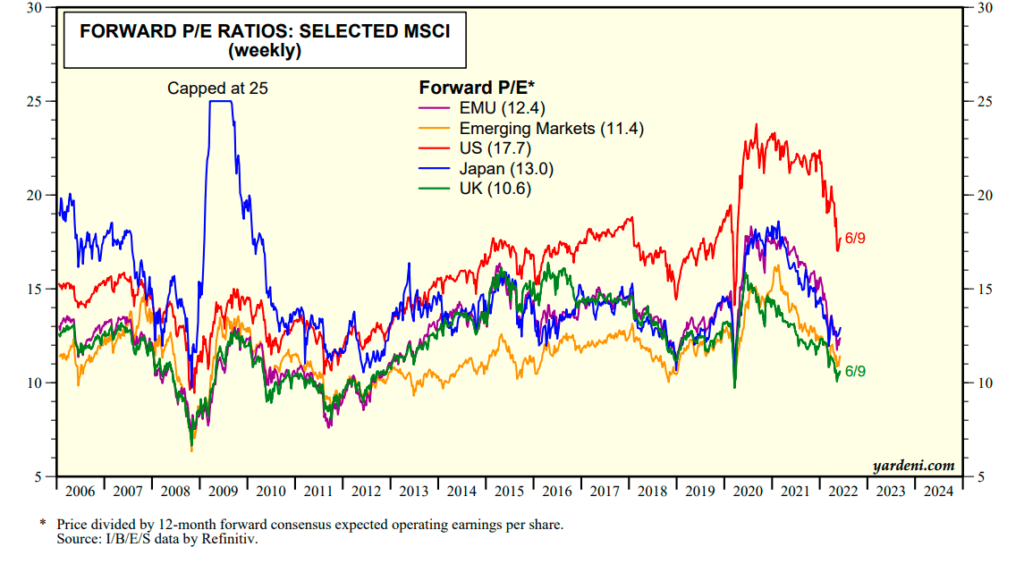

Macro soothsayers will take every opportunity to argue that the US markets went up because of a Fed-driven liquidity bubble. This is the dominant narrative. The Fed has apparently inflated a global stock market bubble by printing money and keeping the interest rates low. But the narrative quickly falls apart if you just spend a minute looking at the returns of the various markets. Much like the Fed, the ECB, BOE and BOJ too expanded their balance sheets massively through quantitative easing. But European equities have gone nowhere while Japan is relatively better. There isn’t a central bank-driven equity rally or an everything bubble—it’s just a US rally.

Ok, if not the Fed printing money and inflating the mother of all stock market bubbles, why did the US markets rally so dramatically since 2008?

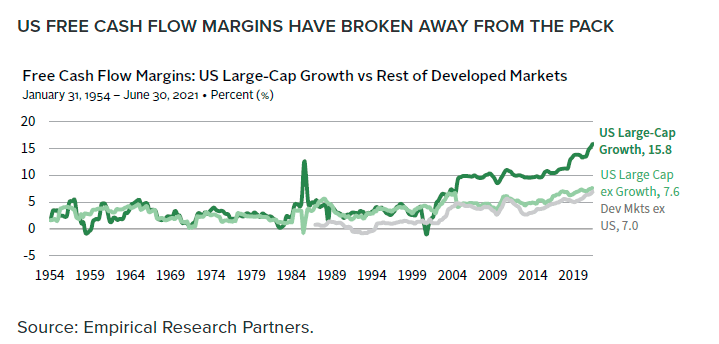

Of course, this is in hindsight, but could it be that US markets had the best fundamentals, robust earnings growth, and profits coming out of the 2008 crisis? Yes, but that’s a dull narrative compared to the money printing and mother of all bubbles narrative.

US free cash flow margins are twice that of other developed markets.

Of course, that isn’t to say that the US market isn’t expensive, but it’s expensive on the back of solid earnings and record corporate profits.

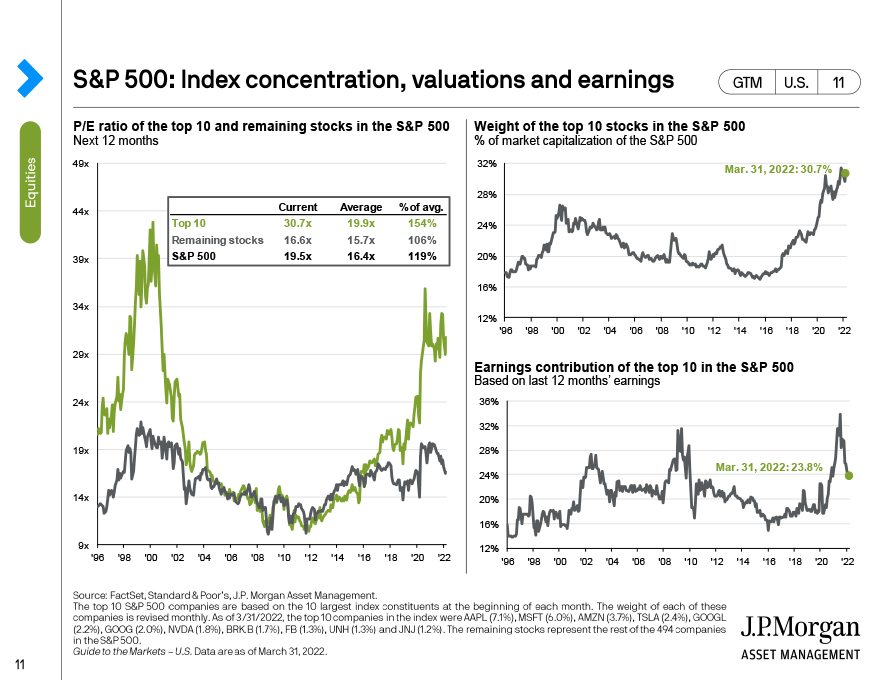

Narrative #2: The US markets went up because of 10 stocks

The moment you say US markets have done well, people will jump like a hungry cat and tell you it’s because of the FAANG stocks. This narrative isn’t incorrect, but it needs some clarification. US markets indeed went up because of the FAANG stocks. If you remove the top 10 stocks from the S&P 500, the returns aren’t that great. But by some weird coincidence, the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 had record earnings growth and were the largest contributors to total S&P earnings.

Surely, this is a cosmic conspiracy?

To the surprise of absolutely nobody, tech companies had the largest EPS growth in the post-2008 period. But this is a very bland explanation compared to 10 stocks are responsible for all of S&P 500 returns, it’s a narrow rally and whatnot.

Narrative #3: The equity flows are propping up the US markets

The other narrative is that all the money flowing into US equities, especially through passive funds, is propping up the US bubble. Umm, US bond mutual funds and ETFs have seen cumulative flows of ~$3.4 trillion, while US equity mutual funds and ETFs have had flows of ~$560 billion. There is money going into US equities, but not as much as people assume.

The theory is that the “permanent bid” through passive ETFs, mutual funds, 401k plans and pension funds are pushing the prices up. Since these automatic flows are mostly price agnostic, there’s sustained upward pressure on stock prices.

There’s a lot of nonsense in this debate. For one, there are a lot of definitional issues with what is passive and what is active. Some people assume smart-beta funds as being passive, but they aren’t. Some of those strategies tend to have higher turnover—it’s basket-based trading, but they are by no means passive. The other assumption is that there’s no trading, but advisors and institutions are increasingly using ETFs to express views like sector bets, thematic preferences etc. There are plenty of creations and redemptions happening all the time. Of course, there’s also the argument that this basket trading is causing other distortions.

The ultimate question, of course, is whether these automatic flows are degrading price discovery?

Flows absolutely impact prices and the market microstructure—there’s no denying that. But are the US markets at the risk of being zombified? Not really. Dave Nadig wrote a brilliant piece recently, summarizing the debate and evidence of this debate.

Narrative #3: Low interest and low bond yields are creating a bubble

Perhaps the loudest narrative is that by keeping interest rates and bond yields low, the Fed and other central banks are creating asset bubbles. This is a loaded narrative, but permabears aren’t fans of nuance.

At the root of this narrative is a somewhat misguided notion that central banks are all-seeing, all-knowing and omnipresent entities. This is partly because monetary policy actions were by and far the most used tool to stabilize economies, generate growth and inflation since 2008 in advanced economies. Fiscal policy was consigned to the policy dustbin until the COVID-19 shock.

Since monetary policy was front and center, central banks have been in the spotlight since 2008. They quickly became punching bags for anything that went wrong in the economy and the financial markets. It’s classic availability bias. Sure, central banks are powerful entities, but their omniscience is greatly exaggerated. But that’s a deeply unpopular opinion, almost bordering on heresy. As Cullen Roche puts it beautifully:

There are all sorts of crazy myths surrounding central banks. Which is strange because once you understand the operational realities of the monetary system you realize that Central Banks are actually pretty boring entities who mostly serve as bank clearinghouses with far less control over the economy than some think. But that doesn’t stop people from constantly blaming the Fed for all of our problems or expecting them to be able to solve every policy problem.

Now to the question at hand: What determines interest rates, and do central banks control interest rates? Central banks set the overnight interest rate or the rate at which banks lend to each other—that’s it. Of course, you could argue that the overnight rates are the base rates that influence all the other rates and yields, but the evidence for that is quite tenuous. They don’t control all the rates—the markets determine them. Of course, central bank actions like signalling, setting expectations, bond purchases etc., do make a difference but not to the extent of the kooky theories peddled by gold bugs and permabears.

Economic conditions and inflation determine the interest rates in an economy. The very simple reason interest rates around the developing economies have been low is because of the nonexistent economic growth and inflation. You don’t have to look any further than the fact that inflation and growth remain low despite central banks adding trillions to their balance sheets. You can also look at what’s happening right now. Central banks are raising rates in reaction to rising inflation and bond yields—not the other way around. But again, this is a boring narrative compared to the central banks are creating asset bubbles by keeping interest rates at zero.

People assume that low interest rates are a recent phenomenon, but they aren’t. Interest rates in advanced economies have been gradually declining for decades and even centuries. Of course, the ultimate question is whether low interest rates impact asset prices and risk-taking?

They do.

Interest rates are used to determine the present value of future cash flows of stocks. In the simplistic notion of interest rates people have, low rates are good for asset prices, and rising rates are bad. But this notion is incomplete. The macroeconomic backdrop in which interest rates rise is equally important. Equities tend to perform well when interest rates rise because of strong economic growth expectations, but they tend to perform poorly when rates rise due to strong inflationary pressures1,2.

More importantly, the effect of interest rates isn’t uniform on all sectors and styles. Some stocks may have higher sensitivity but the impact varies across sectors and styles. The underperformance of US value stocks for more than a decade despite the low interest rates is a case in point.

You also must grapple with the question of defining what is risky? Except for the most egregious speculative activities, defining what’s risky becomes tricky. Having said that, at a broad level, if you define risk-taking as allocating capital to relatively risky assets, then yes, low interest rates have been shown to increase risk taking1,2,3. Corey Hoffsten had published a brilliant paper looking at some of the same narratives in this post. Here’s an excerpt from that paper:

The cause of this transmission is obvious when we consider that many investors – including pensions, endowments, insurance companies, and individual investors – have fixed dollar liabilities and/or fixed percentage withdrawal plans. When return targets can no longer be met with U.S Treasuries, investors must bear incremental risk to seek higher returns. Ironically, increased demand for higher risk assets may reflexively reduce risk premia, forcing investors even further out on the risk curve. In Figure 2 we can see how the blend of assets providing an expected 7.5% return has changed over time. An investor seeking to achieve a 7.5% return must now take nearly three times the risk (as measured in standard deviation) compared to an investor in 1995

The problem is with the sweeping claims that low interest rates were the sole driver of asset prices over the last decade. It’s a case of confusing correlation with causation.

Having said that, low interest rates do have serious consequences. But at the same time, the impact of unconventional monetary policies has been vastly exaggerated. In scientific and academic terms, the impact of all these policies can be summed up as they kinda, sorta work, but not really too well, but enough to have some sorta impact, but we know something but not too much and measuring is difficult but we have some sense but not a whole lot1,2,3. The bigger problem when analyzing the impact of unconventional monetary policies is that they’ve only been used over the last decade.

To complicate matters, incentives and human foibles muddy the picture when measuring these things. There was a brilliant and hilarious paper titled “Fifty Shades of QE”, which looked at the role of incentives in research on quantitative easing (QE) published by academics and central bank researchers. The authors showed that central bank researchers tend to overestimate the impact of QE compared to academic researchers. They also showed that central bank researchers that showed a larger impact of QE in their studies had favorable career outcomes. This impact was stronger for senior central bankers. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry at this.

Thankfully, there are a growing number of studies on the impact of low interest rates on financial stability, credit, inequality, market structure etc. Here are a few research papers to give you a sense of the questions researchers and academics are exploring.

- The BIS, IMF and other researchers have published numerous studies on the financial stability implications of low interest rates.

- Viral Acharya has shown how low interest rates work against the objective of central banks to create inflation by causing deflation. His research also shows that low interest rates incentivize banks to keep lending to useless companies, leading to zombie firms.

- Perhaps the loudest debate is over the impact of low interest and unconventional monetary policy on inequality. There’s a growing body of research on this1,2,3,4.

- The impact of lower interest rates on market power and market concentration. Atif Mian et al., Romain Duval et al., Andy Haldane, Nathan Tankus, Jan Eeckout and Jan De Loecker, among others.

These are just a few of the amazing people doing amazing work on the side effects of throwing the kitchen sink monetary policy over the last decade. This short list doesn’t nearly do enough justice to the others.

Hopefully, we’ll learn more as more research comes out. Of course, it won’t matter if that one guy who’s been 100% in gold since 2008, betting on the imminent implosion of the modern financial system, turns out to be correct.

Ok, so there are no bubbles?

This question becomes relevant only if you agree with the premise that not everything is a bubble. If you don’t, then right now, you have a full HD view of a slow-motion implosion of the greatest financial bubble in the history of humanity. But if you’re a moron like me who believes in nonsense like nuance, you would have realized by now that not everything is a bubble.

As an aside, the other issue with screaming there's a bubble is what exactly is a bubble, and how do you define it? On the one extreme, you have people like Eugene Fama that are of the view that there's no such thing as a bubble. On the other extreme, you have people like Robert Shiller that think otherwise. This is the exact debate that led both of them to share a Nobel Prize.

So, where are the bubbles?

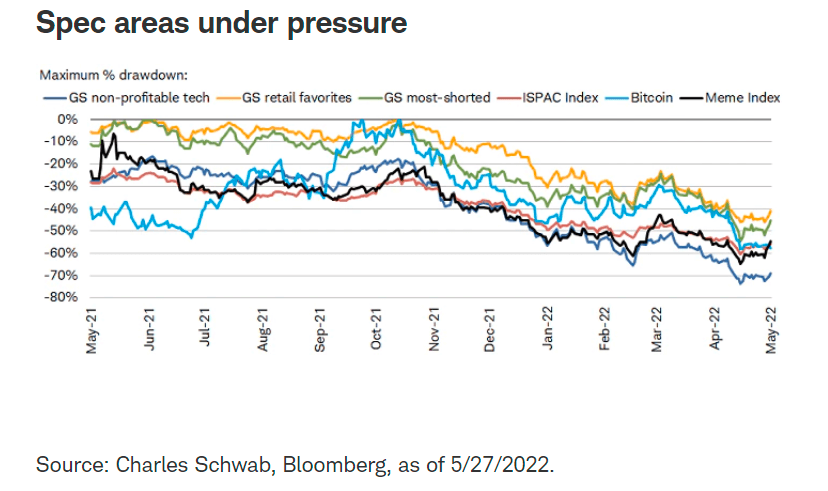

Growthy stonks

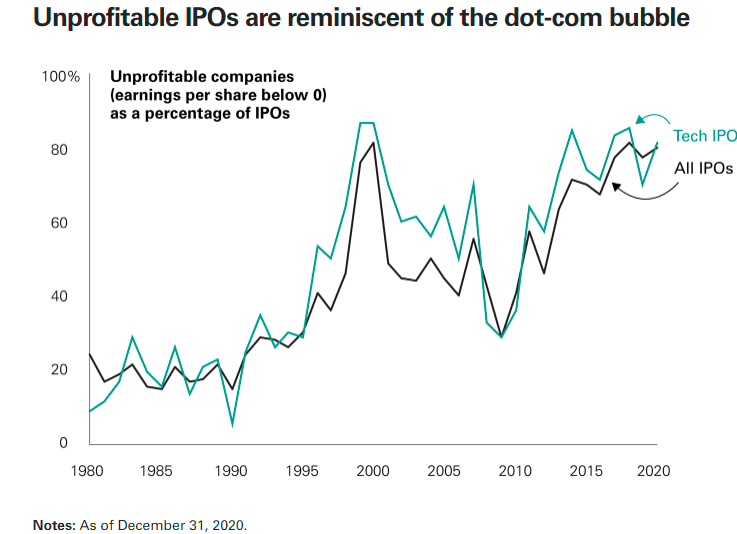

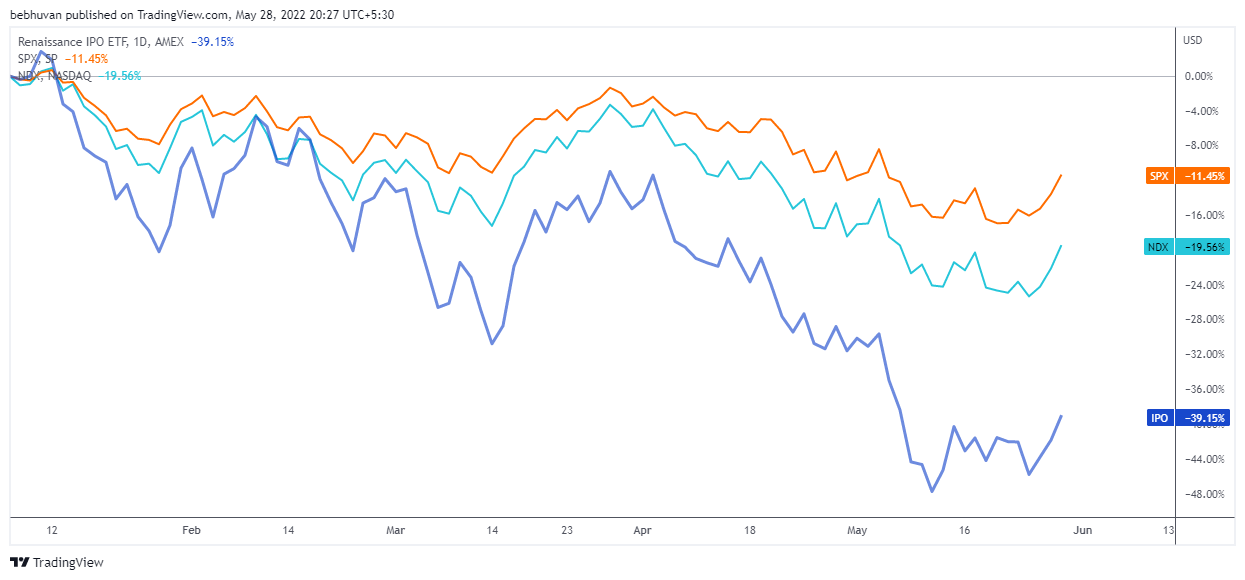

There was indeed some insanity on 10x leverage in some market segments, especially the growth stocks. Over the past decade, there were a record number of unprofitable IPOs, the bulk of which were the so-called new-age tech companies. These companies were sold on pitches of disruption, destruction and world domination. The fervor around these stocks was reminiscent of the dot-com bubble. As long as a company had something remotely to do with tech, the IPO would be oversubscribed. Revenues and profitability didn’t matter. The more the losses, the better it was.

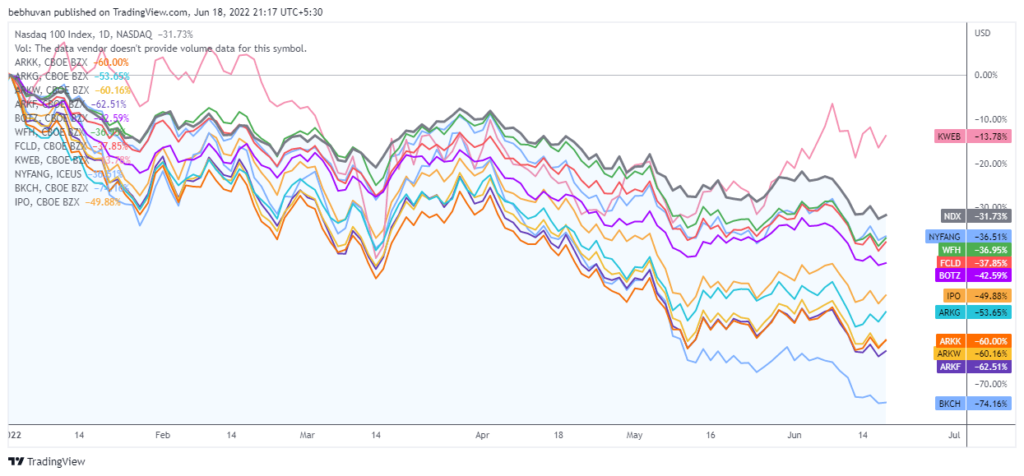

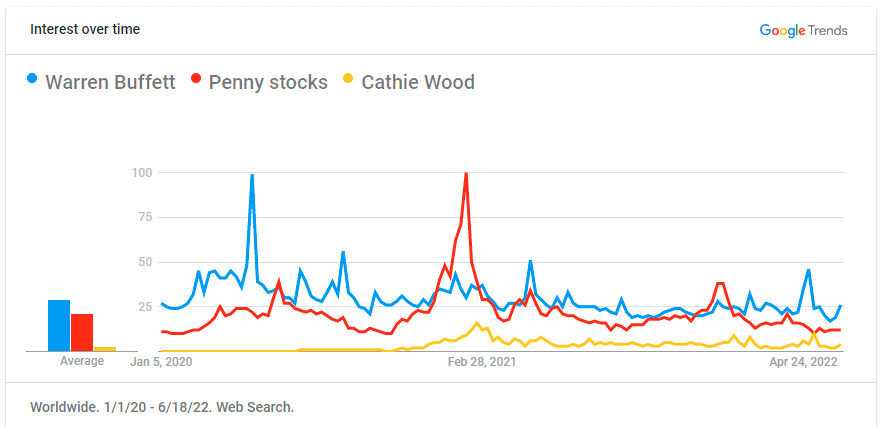

Things got a little more unhinged after the pandemic. Tech and internet stocks became the new darlings due to the shift to remote work. Hundreds of tech, internet, disruptive tech, biotech, robotics, space, AI, next-gen tech and other nonsensically labelled ETFs were launched to take advantage of the demand. Nothing was more emblematic of this fetish for growthiness than Cathie Wood’s ARK ETFs. These funds are now falling as if there’s no bottom.

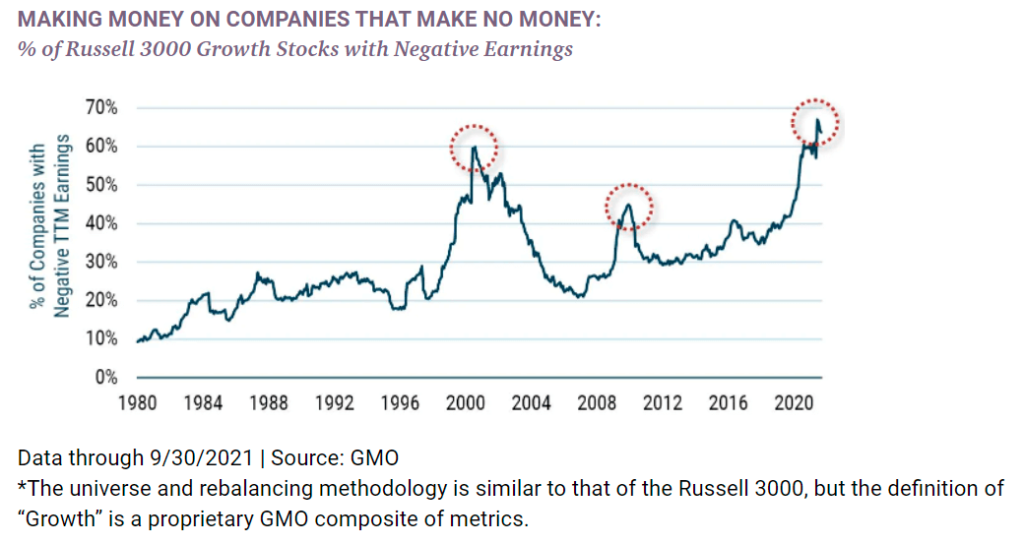

Jeremy Grantham found that half of the growth stocks in the Russel 3000 index had negative earnings. He had been screaming about a bubble since 2010 and wanted a crash so badly that GMO created a composite growth metric, just so that he could make this scary chart 😂 No, I kid.

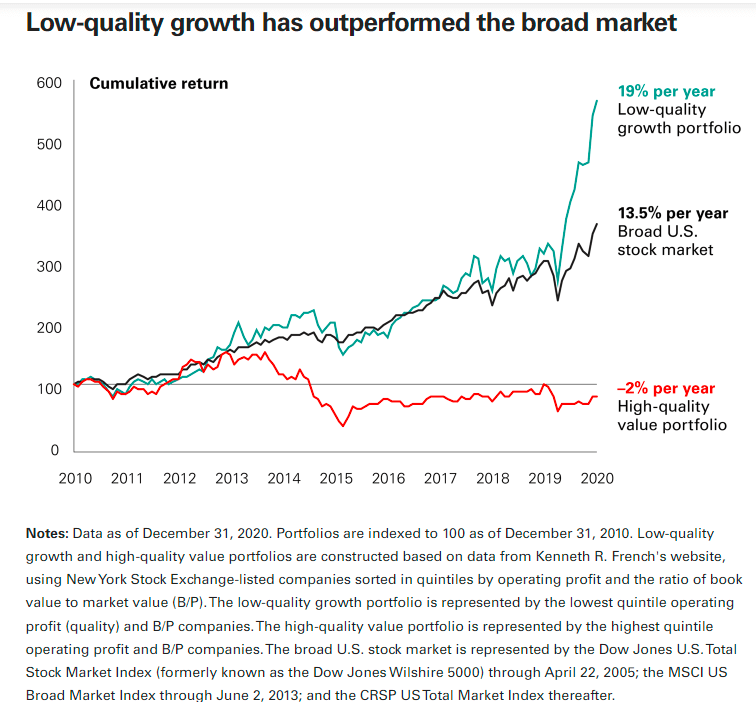

Until this year, the markets didn’t care. Buying a basket of companies with the worst possible fundamentals was the best trade. Talking about earnings and fundamentals was the surest way to look foolish.

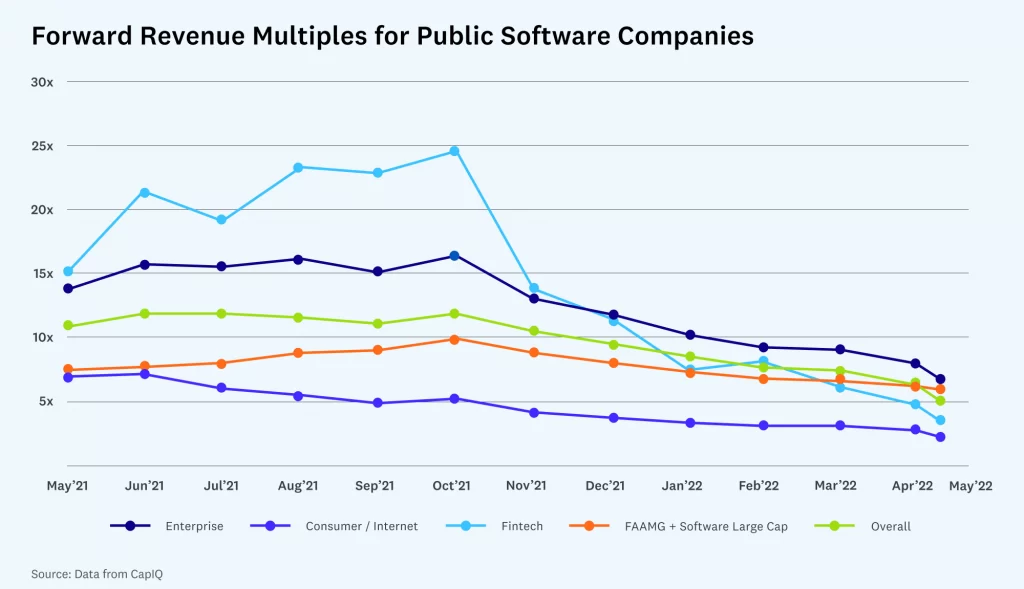

The one stock that was symbolic of the growthy craziness that immediately comes to mind is Rivian, the electric car startup. At one point after its IPO, the company had a market cap of $100 billion+, which was higher than General Motors and Ford despite having zero revenue. The other bubbly segment was SaaS companies. Some of these companies were trading at over 25 times their revenues, but as of May 2022, the median revenue multiple has fallen to ~5 times.

Why?

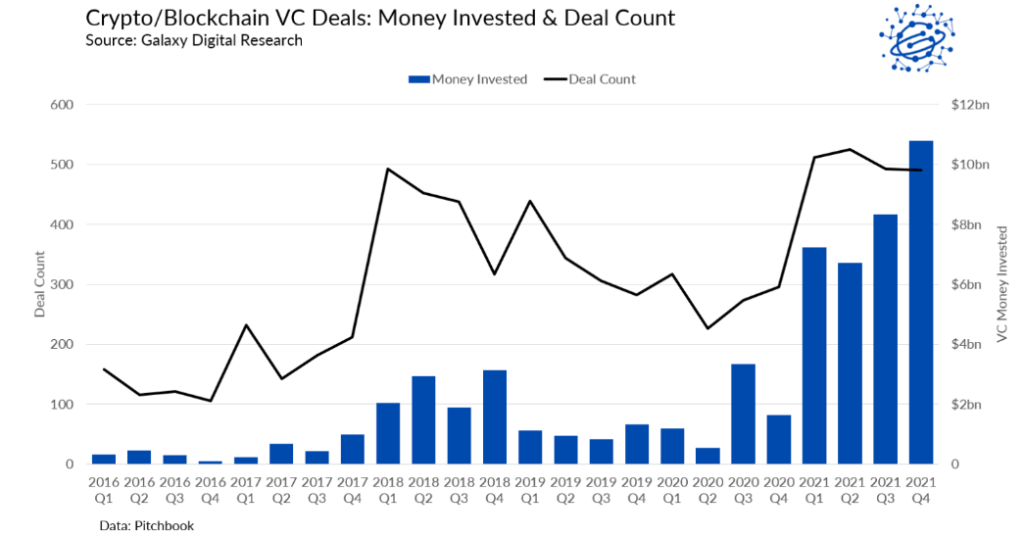

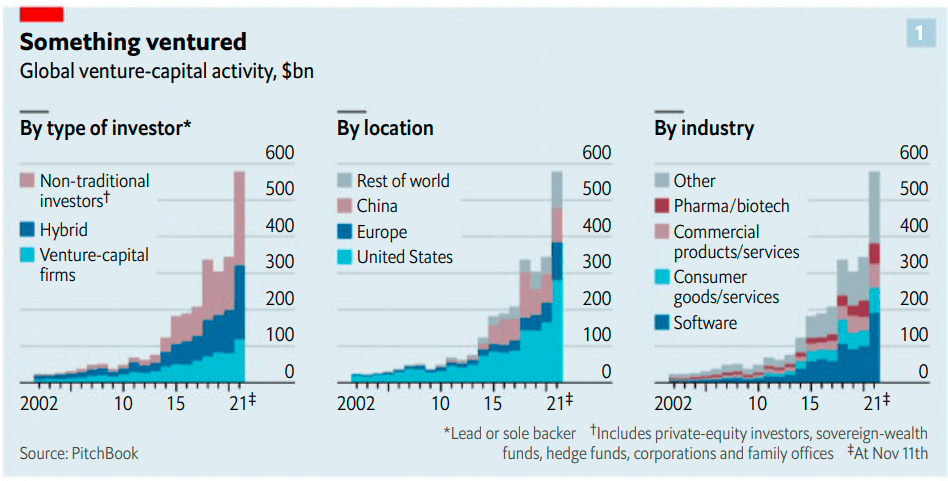

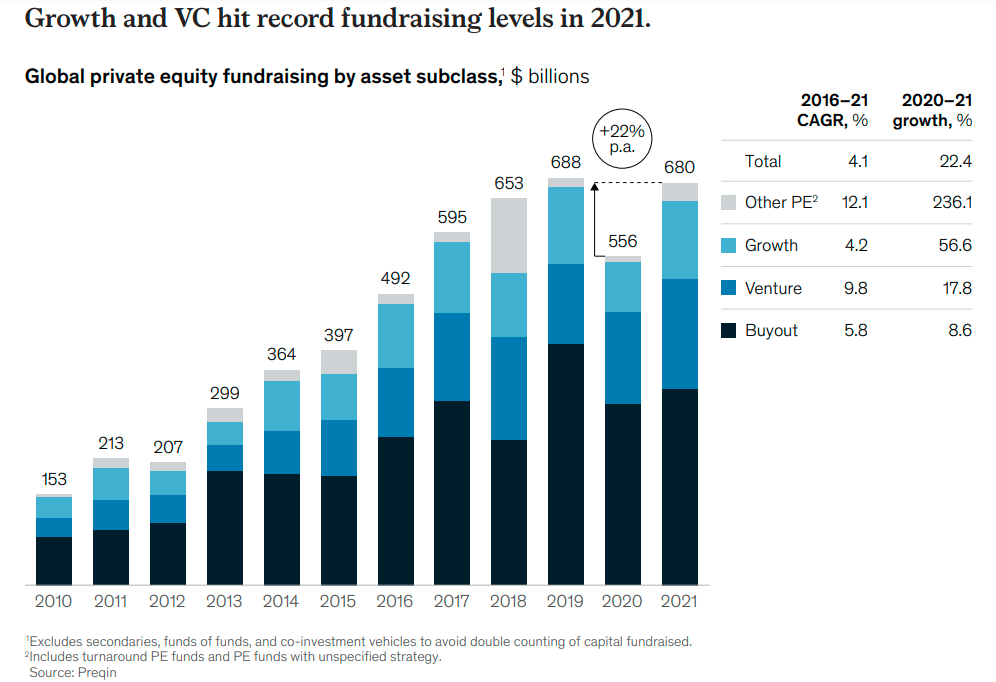

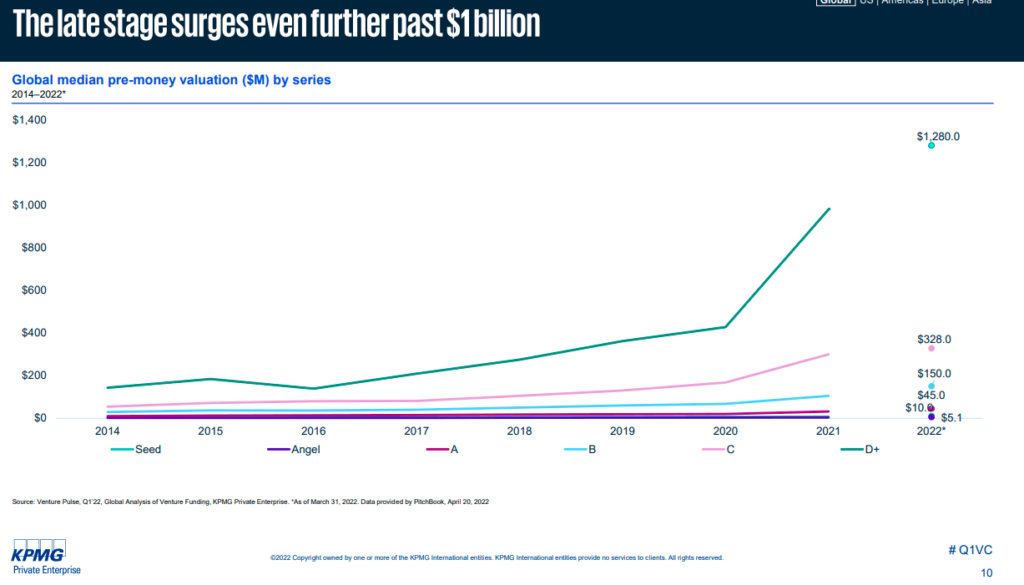

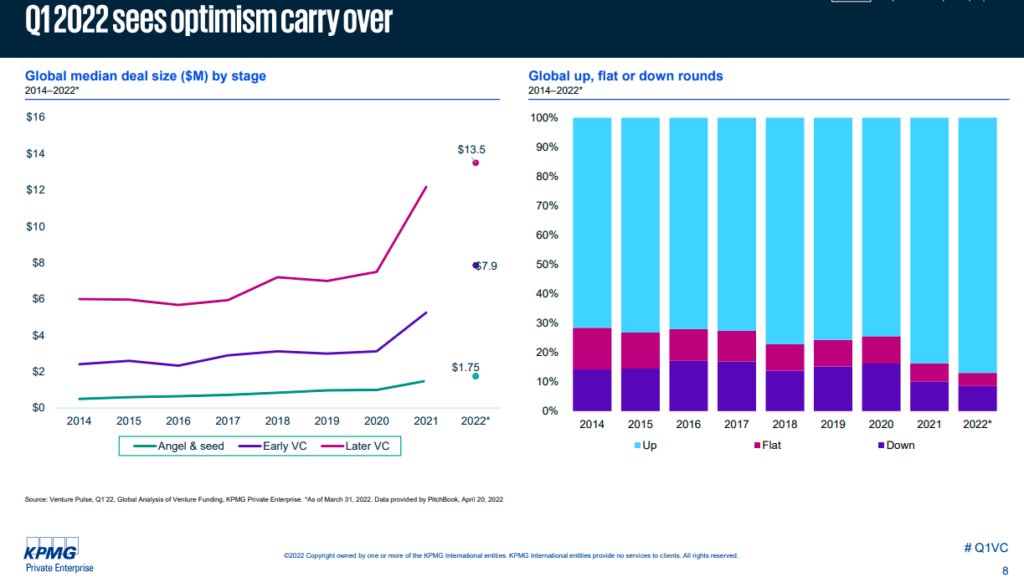

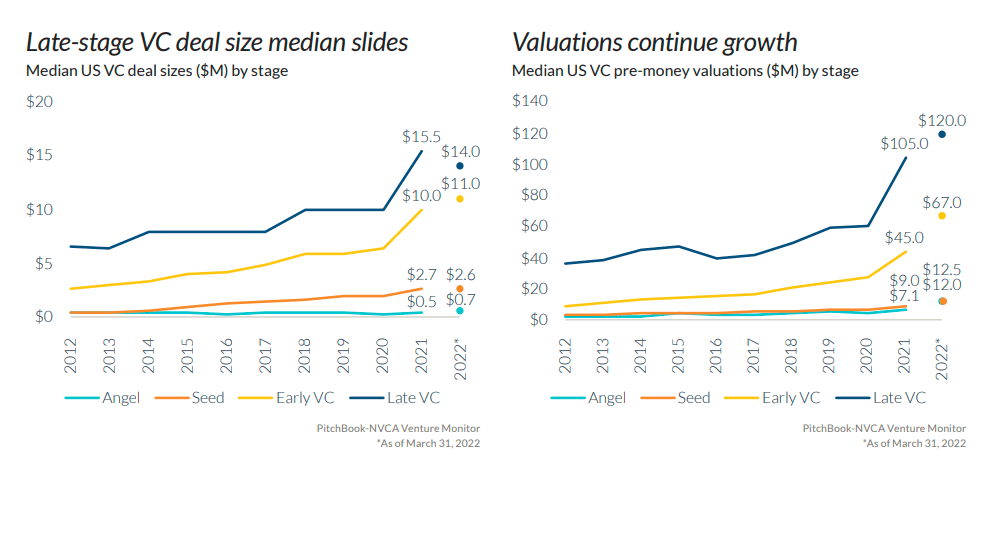

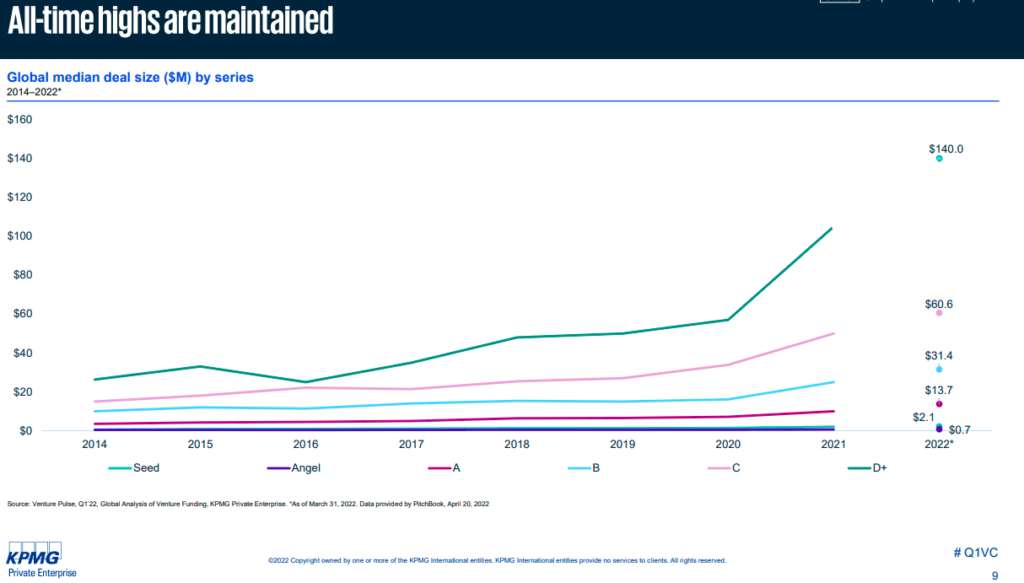

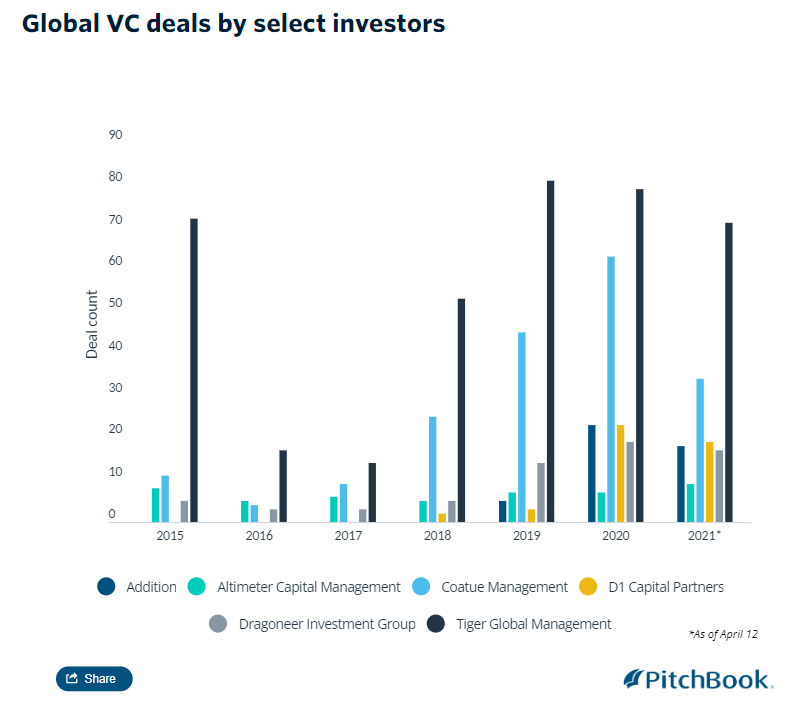

This glut of growthy stocks was due to the incredible growth of venture capital in the US. Every year since 2010 has been a record-breaking year for venture capital, not just in the US but worldwide. There were a record number of new funds, deals, valuations and record records. Perhaps one of the most important developments in venture capital was the entry of price agnostic non-traditional venture investors like Tiger. Capital became a commodity, and valuations became an afterthought.

In the last 2-3 years, FOMO took over as funds were investing as if they were throwing blind darts. They were increasingly piling into the same set of companies and rapidly marking up the valuations. Deals were being closed in hours and days, and due diligence was a dirty word, just like fundamentals. Founders went from pitching to VC funds to getting pitched by VC funds. You could ask your grandma to pitch an idea, and Tiger Global and Softbank would get into a cat fight to fund her. There was no difference between a pump and dump scheme, and venture investing.

All these stocks are now crashing twice as fast as they went up. I’ve been getting unconfirmed reports that the most heard song by the CEOs of these companies was Livin’ on a Prayer by Bon Jovi.

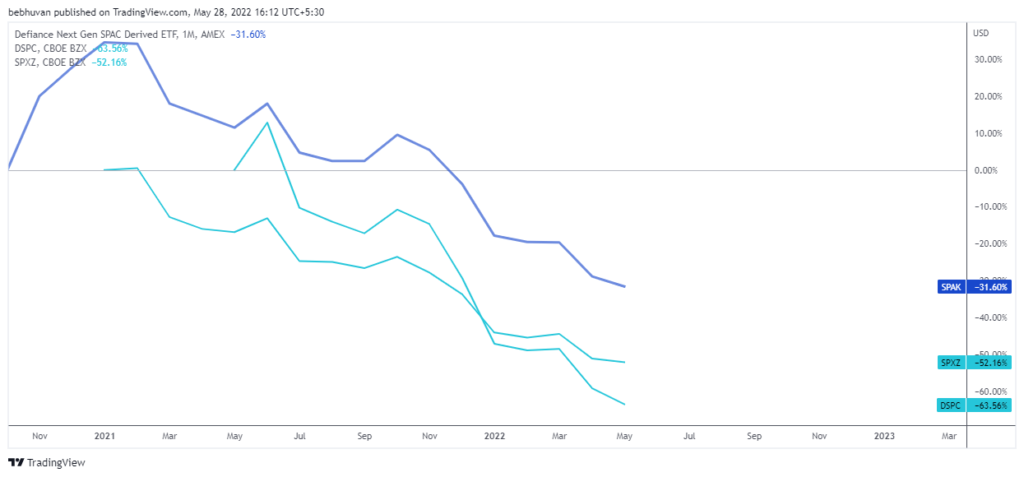

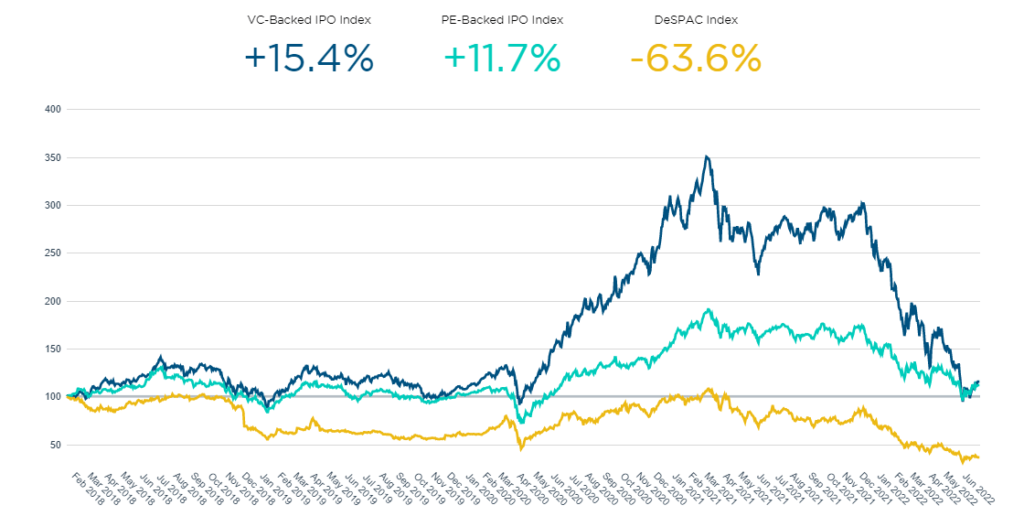

SPACtacular implosion

Every crazy market phase has a poster child. Nothing compared to the sheer insanity of the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). SPACs are blank check companies that raise money to acquire or merge with other companies. They are similar to IPOs, but with lesser regulatory hassles. The problem is that they are also costly, opaque and heavily dilute retail investors. They’re also quite lucrative for the sponsors of SPACs, who typically get 20% of the post-IPO shares for free. These skewed incentives attracted everybody, from shady operators to Hollywood celebrities.

Ohlrogge and Klausner, a professor at Stanford Law School, discovered that these costs quickly added up: The dilution from warrants issued in the IPO, along with virtually free shares for sponsors and banking fees for both the IPO and the merger that ended up being two to three times higher for a SPAC than for a traditional IPO, all ate into the amount of cash the companies had once the merger happened. Because the companies passed on these costs to the remaining shareholders, the companies ended up with about 40 percent less cash than they started with.

SPACs became the go-to vehicle to take companies public over the last couple of years. But most of these companies were useless and downright fraudulent in some cases. Regular IPOs can’t make projections or forward-looking statements in the US due to liability issues. But until March, SPACs could make projections because of a safe harbor provision. SPACs exploited this regulatory arbitrage to make wildly optimistic projections unsullied by reality to dump the stock of worthless companies on retail investors. SPACs raised over $250 billion in 2020 and 2021, but the party is over. Given the market sentiments, SPACs will have no choice but cancel, and return the cash. Companies that listed through SPACs have been getting a royal spanking, with most of them down by over 30-50% YTD.

In recent weeks, 25 companies that went public through SPACs have issued warnings that they may die in the next 12 months. I think this is just the beginning. Most companies that went public through SPACs have no business models and will die eventually.

Perhaps, this from Jim Chanos sums up the extraordinary scale of the SPAC delusion.

But what was really striking to me was the fact by February of 2021 for a couple week period, SPACs were raising, new SPACs were raising on average 3 billion in cash every night. And that was equal to the US savings rate. So for a brief period of time SPACs were taking the entire US savings rate, which just struck me as the height of absurdity.

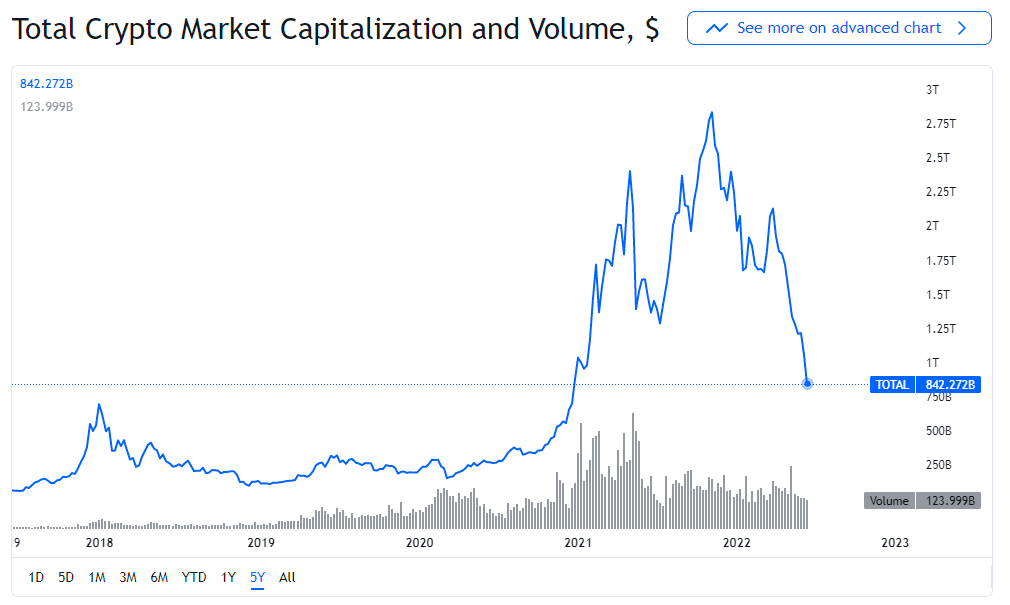

Crypto

Crypto and SPACs are almost similar; both involved dumping worthless stocks and tokens on greedy investors. The only difference is that SPACs are “regulated”, and crypto isn’t.

Every ~4 years, we see a new crypto hype cycle that always ends in tears, broken dreams, empty wallets and margin calls. In 2017, it was the ICO boom. Hundreds of projects raised billions by selling tokens to build everything from a blockchain-based casino, decentralized AWS, to a blockchain-based phone. There was an insatiable demand for these projects. If you could publish a white paper with utter gibberish and techno babble, you could raise millions. The ICO mania ended when the SEC began cracking down on some of the coin offerings.

This time, the the rise of decentralized finance (DeFi) fuelled the mania. DeFi boosters believe that traditional financial institutions like banks, insurance companies, exchanges, and asset managers are overpriced, bureaucratic and incompetent entities. Their vision was to eliminate all these “rent-seeking” entities and replace them with smart contracts. Code is law became the mantra. This apparently would lead to borderless money and bring about financial inclusion on a scale never seen before. Sounds nice in theory, but most DeFi projects ended up being Ponzi schemes in reality. Charles Ponzi would’ve been proud of crypto; this is the dream he died for.

Here’s how most DeFi projects worked. A developer would start a project that claimed to revolutionize XYZ., and the project would launch by issuing a few tokens. It would also create a liquidity pool where token holders can deposit the tokens to earn interest in exchange for providing liquidity in the tokens. As an incentive for providing liquidity, the project would reward the holders with more tokens, which can be staked again in the liquidity pool to earn more rewards. This would cause the price of the tokens to rise, naturally attracting more people to buy the token. As more people piled in, more incentives would be paid out. This cycle could last as long as there were willing suckers. But the issue with the model is people bought the tokens for the rewards and not for their utility. A negative trigger like a fall in prices, hacks, vulnerabilities, or attacks would cause the projects to spiral out of control and die eventually.

The speculative fervor wasn’t just limited to DeFi. The mania was such that random tokens with zero utility would rise by 100-1000% in a span of weeks. Perhaps, nothing was more emblematic of this utter insanity than Dogecoin, a token that was created as a parody of crypto. At one point, the marketcap of Doge was over $40 billion; it’s still around $7 billion. It wasn’t just random shitcoins, the other poster child of this season’s crypto madness was NFTs or “digital art”, basically pictures of rocks, dogs and monkeys that sold for millions.

As long as you knew some basic coding, you could launch a token or create an NFT within 5 mins. There was an entire cottage industry dedicated to pumping crypto projects and NFTs on Telegram, WhatsApp, Reddit and Discord for a few dollars. Once the pump was in, you could dump them and make easy money. Rising crypto prices attracted more suckers, which fed the cycle, ensuring a limitless supply of victims. Crypto became a hunting ground for hackers and scammers. Unwitting investors have lost billions due to hacks and exploits.

Naturally, the VCs saw an opening and co-opted crypto. They even rebranded it to “web3.” A worldwide investigation is underway to ascertain the meaning of the term. Venture capital firms like a16z, Paradigm and exchanges like FTX, Coinbase and Binance invested billions in crypto and blockchain startups.

Of course, this wasn’t without side effects.

Crypto projects went from being “community-powered” and “decentralized” to increasingly resembling traditional startups. VCs and insiders now control a vast majority of the token allocations. This has led to fears of token dumps by VCs, potentially kneecapping projects. VCs have also used their resources to engage in cringe-worthy crypto boosterism and massive self-dealing to pump prices. Many exchanges like Coinbase, FTX, and Gemini have listed tokens in which they are large investors. There have been long-running allegations of information leaks about token listings on Coinbase, leading to informed insiders building large positions and dumping them on listing day. Coincidentally, a16z is the biggest investor in Coinbase and crypto broadly. Even more importantly, the tokens listed on Coinbase underperformed dramatically. If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck…

It’s been a gratuitous display of greed, grift, shilling, self-dealing and downright fraud. Very little of what passes for web3 has valid real-life use cases today. Web3 has recreated all the traditional finance applications but only slower, scammier, and uglier. Even the most ardent crypto boosters can’t come up with a coherent use case for web3:

And then you have the clinically crazy people 👇

When you question the crypto boosters about the shortcomings of web3, you’ll typically hear some spiel about innovation and the future. Here’s Katie Haun, who recently left a16z and raised a $1.5 billion crypto fund:

Well, I think it’s important not to judge the current state of innovation in crypto with the end state of innovation. And people such as yourself will often tell me, well, wait a second. It doesn’t do that yet. And look, I’ll be the first to acknowledge that the applications we’re talking about — still very early days with Web 3.

katie Huan on The ezra klein show

Not even the most ardent crypto fanatics can deny all these things. Despite sounding negative, I’m deeply ambivalent about crypto. Maybe this is how “innovation” works, I don’t know.

As things stand, crypto is getting shellacked. We’ve seen several high-profile blow-ups in a span of weeks. It started with the spectacular implosion of the $40+ billion Terra stablecoin project. Celsius, a platform that paid high interest rates on crypto deposits with over $12 billion in assets, was next—last week, it froze all withdrawals. This week, crypto venture/hedge fund Three Arrows Capital collapsed after the recent rout in crypto prices, and the demise of Terra led to margin calls it couldn’t fulfil.

Some projects have survived and thrived at the end of every crypto cycle. But this time around, the risk for crypto is that it’s mainstream. They now mimic traditional financial institutions like banks, asset managers and exchanges without any oversight and billions in assets. Regulators have been spectacularly incoherent in dealing with crypto so far, but things are changing. More often than not, the preferred policy option has been to make life extraordinarily difficult for crypto, like imposing high taxes than outright banning them. But we’ll have more coherent regulations in the years to come.

So what does this mean for crypto and DeFi?

I think crypto will eventually become far more boring than it seems today. This will be a deeply unpopular opinion, but DeFi has seen more innovation in a few months than traditional financial institutions in a decade. I mean, sure, the DeFi boys have channelled the spirit of innovation into finding the ultimate pump and dump scheme, but it’s innovation nonetheless. Now, imagine if they channelled it productively?

Heck, even The Bank for International Settlements thinks so:

The limitations of DeFi lending mask elements of genuine innovation. Smart contracts can complement automated underwriting in traditional finance and help to bring down the costs of financial intermediation (IMF (2022)). Composability – the ability of DeFi protocols to interact with one another – allows end users to combine various “money legos” to build customised financial products. This possibility can be particularly relevant in complex chains of transactions such as trade finance.

DeFi lending: intermediation without information?

Or maybe we’re all skeuomorphic dolts, we don’t get what crypto is, and we’re not going to make it.

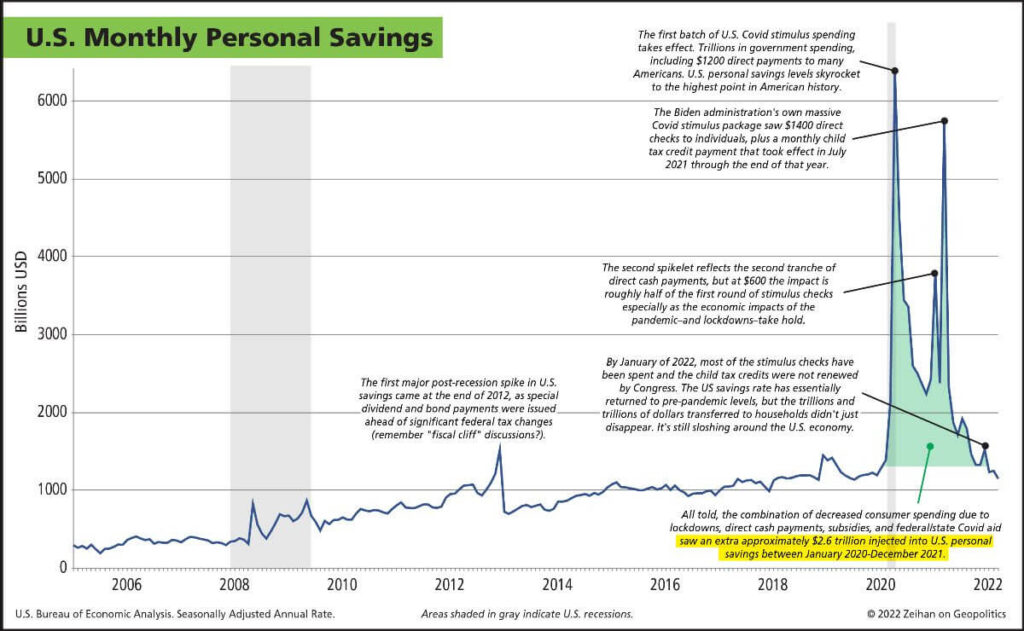

The great detox

Maybe all these crazy people thought this could go on forever or at the least for longer, but the virus had other plans. One of the reasons for the slow recovery post the 2008 crisis is that the US did almost nothing to help the people directly. The Fed was left to do the heavy lifting through monetary policy. Things were worse in Europe. Austerity was the only policy option during the 2008 and the Eurozone crisis. The European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forced the crisis-hit countries to cut spending, slash social security programs, privatize state assets and tighten their belts. This monumental stupidity lengthened and deepened the crisis. The absence of fiscal measures was one of the big reasons for the slow recovery after 2008.

But in 2020, it was different. As the pandemic hit, countries around the world—especially the developed countries—unleashed economic stimulus programs on a scale never seen before to stop the global economy from going back to the dark ages. Advanced countries threw the kitchen sink, including handing out free cash to people, to put a floor under the economy. Countries unveiled trillions worth of programs in weeks.

Here’s a stunning chart that shows the total savings of Americans. US consumers got ~$2 trillion for free from the government. This stimulus was designed to bridge the economic output gap due to the shutdowns. With the luxury of hindsight, people now argue that the stimulus was way too much and inflation is a direct result.

As the economies around the world reopened, there was a tremendous rebound in consumer spending. But the world wasn’t prepared to deal with it.

- As countries locked down, shipping companies dumped shipping containers at their destination ports as shipping demand vanished. When the world reopened, containers were stuck in all the wrong places.

- Due to the pandemic, many people dropped out of the labor force across industries due to health reasons, poor pay, poor working conditions, and mobility due to better bargaining.

- As the factories around the world reopened, they faced severe labor shortages. At the same time, since shipping containers were stuck in all the wrong places, factories couldn’t ship finished goods and receive raw materials for production.

- Global shipping demand and port activity were flat for nearly a decade. But the epic surge in demand was more than the slack in shipping and port handling capacity. To make things worse, both shipping companies and ports were facing labor shortages and the biggest demand surge in decades at the same time. This fed into trucking, which also faced a shortage of drivers and trailers.

- The Russia-Ukraine crisis, rolling lockdowns in China, and trucking protests in South Korea, further intensified the pressures.

- In short, all these factors severely disrupted the normal flow of raw materials, intermediate inputs and finished goods.

- This manifested in shortages of everything from critical manufacturing inputs like semiconductors to toilet paper.

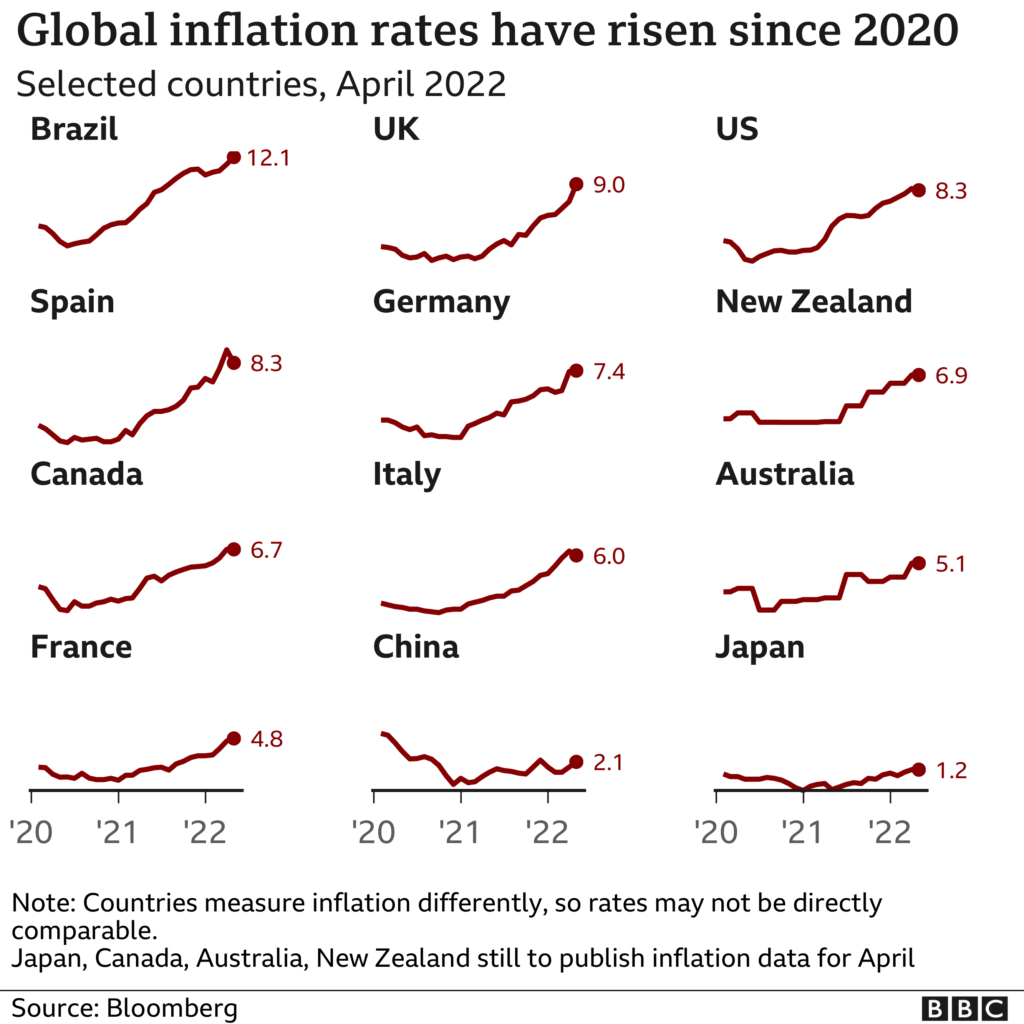

The advanced economies have been praying for inflation since 2008, and their prayers went unanswered for well over a decade. But thanks to the idiosyncratic global reopening, the simultaneous spike in demand for goods, fall in supply, and energy shocks, inflation showed up with a vengeance.

Governments and central banks initially assumed that inflation would be transitory, and it would pass—it didn’t. Even I assumed this would be transitory, and boy was I wrong. The Russian invasion of Ukraine further intensified the inflationary pressures. The Fed and the ECB, which had kept interest rates low, could no longer sit idle. The Fed is now hiking rates aggressively, and the ECB will follow suit in July. The central banks in emerging markets had started hiking much earlier.

A decade of low interest rates, increased retail participation, and pandemic stimulus cheques had led to excesses building up in some segments of the markets. But this rising rate environment has become a nightmare for these frothy corners of the markets. We’re seeing massive bloodletting across the board, but it’s particularly gory for growth stocks. It’s like popping a balloon.

The craziest segments of the market, such as meme stocks, unprofitable companies and crypto, are in free fall.

Here’s a shocking titbit.

The pace of multiple compression has been brutal.

All the analyst estimates that missed earnings are now getting revised. If earnings take a hit, will things get even uglier?

Meanwhile, thee yoots (youths) have discovered Buffett

Private markets

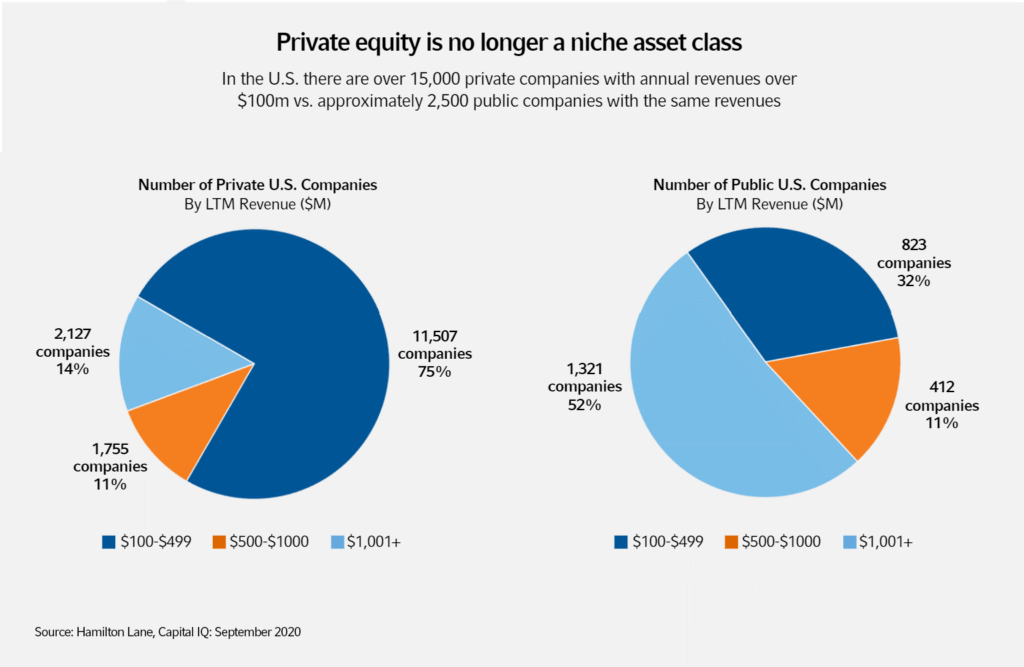

The US private markets (venture capital & private equity) are tiny compared to US public markets. But over the last decade, much of the action has been in the private markets. The public markets were largely a sideshow. Companies have raised more capital in private markets over the last decade than in the public markets.

U.S. domestic equity mutual funds manage about $8.4 trillion, with active funds controlling $5.6 trillion and index funds $2.8 trillion at year-end 2019. Buyout funds in the U.S. have $1.4 trillion in assets under management (AUM), including $560 billion in “dry powder.” Venture capital funds have AUM of approximately $455 billion, which includes dry powder of $120 billion. The equity capitalization of the U.S stock market is roughly 27 times the size of AUM for buyout funds and more than 80 times the size of venture capital funds.

Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look

The Cambrian explosion in US tech and software startups over the last decade is because of the phenomenal growth of US venture capital. Venture activity had declined significantly after the dot-com bubble in 2000-2001 but recovered spectacularly after the 2008 crisis. Without the easy availability of risk capital, the US startup scene would’ve been a pale shadow of today. We can see the counterfactual in Europe, which doesn’t even come close to the US in terms of new startup formation, let alone successful tech startups. This is largely because European Venture capital is still tiny, and the availability of risk capital is directly correlated with startup formation.

Why did US venture capital grow so large compared to the rest of the world?

Narrative #3: The Fed caused the VC bubble!!!

This is the point where people typically blame the Fed. I think most people have a Moriarty or Keyser Söze-like image of central banks—shadowy entities that mysteriously control everything.

US venture capital didn’t grow because of the Fed. It’s big because the US is the wealthiest country on the planet, with the largest institutional pools of capital and the highest number of rich people. That isn’t to say the low interest rate environment didn’t help. Of course, they were a tailwind for private markets, but you also have to understand how private markets work.

Unlike public equities, private market investing cycles are much longer, and investment decisions are much slower, not to mention the risk and the illiquidity constraints of institutional investors. Suppose a pension fund were to make an allocation to venture capital. In that case, it has to make a case to its investment committee, build the expertise, go through the manager selection process and then make the final allocation. Institutional investors aren’t exactly known for their nimbleness. On the other hand, a well-run venture fund (non-Tiger style) takes time to deploy the capital, it doesn’t happen at the same pace as public equities. In short, low interest rates alone don’t explain the growth of private markets. It’s another case of confusing correlation with causation.

A little bit of VC history

It’s important to understand a bit of venture capital history to understand the growth of US private markets. Some people argue that Queen Isabella of Spain, who funded Christopher Columbus’ voyage, was the first venture capitalist. Spain needed a faster route to Asia, and Columbus promised Isabella he would find one. So she gave him three ships and some men in return for 90% of the profits. Instead of Asia, Columbus discovered the Caribbean islands or the new world and unleashed the golden age of exploration. The discovery eventually led to Spain’s colonization of the Americas, and the investment paid off brilliantly.

Until the 19th century, whale oil was quite valuable, and America had emerged as the leader in whaling. Whaling ventures—finding and hunting whales—were long and costly, and banks didn’t fund them. But some wealthy individuals were willing to take the risk, and on the other hand, you had ship captains who needed the capital—whaling agents emerged to intermediate these deals. As Tom Nicholas wrote in VC: An American History, the funding of whaling ventures, the structure of these partnerships and the return profiles were almost the same as modern-day venture funds.

Before the formalization of venture capital, descendants of wealthy families like Rockefellers and Whitneys played an important role in providing risk capital to early entrepreneurs like Henry Ford and George Eastman (Kodak). The other crucial factor that led to the growth of venture capital was the massive funding of universities like Stanford, Harvard and Caltech by the US Government during World War 2 to create military technology. This would create massive spillovers in terms of new entrepreneurs, technologies and led to the birth of Silicon Valley.

In 1946, Georges Doriot, a professor at Harvard Business School, set up American Research & Development Corporation (ARD)—arguably the first formal venture fund. Doriot is also called the father of venture capital. One of the most well-known investments of Doriot was in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). The $70,000 investment would eventually become over $350 million, cementing ARD’s status as one of the great VC firms ever.

SBICs

The other important event which laid the ground for the growth of venture capital was the passage of the Small Business Investment Act In 1958 in the US. The act allowed the creation of small-business investment companies (SBICs) to support small businesses. SBICs received various loan guarantees and tax concessions to invest in startups. Over 700 SBICs were formed, and several of the firms were listed publicly during the bull markets of the early 60s. But soon, the stock prices of SBICs tanked, and they were in serious trouble. Investigations by the Small Business Administration revealed serious regulatory violations and downright fraud. With SBICs, venture capital looked like it would hit the mainstream, but it just faded away. The program was largely a failure. This was the period in which several of today’s venture giants, such as Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia, were born.

The most consequential change

Perhaps the biggest changes that unleashed venture capital occurred in the 1978-79. The most consequential change was the amendment to the “prudent man” rule of The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). The rule required pension fund managers to act as fiduciaries and invest prudently. At the time, pension funds assumed that rule meant that they should avoid risky investments like venture capital. But in 1979, The Department of Labor clarified that investing a small portion of pension assets in venture capital wouldn’t violate the rule.

In 1980, US pensions had $3 trillion in assets and had only about ~$200 million in venture capital investments. By 1988, this would grow to $3 billion, accounting for 46% of VC funds raised. The other significant change was the reduction in capital gains tax from 50% to 28% in 1978. There is some debate over the impact of the tax reduction, given that the biggest VC investors, like pensions and endowments, were already tax-exempt. But others argue that the reduction in taxes could’ve worked indirectly by making it attractive for people to start new companies, increasing the supply.

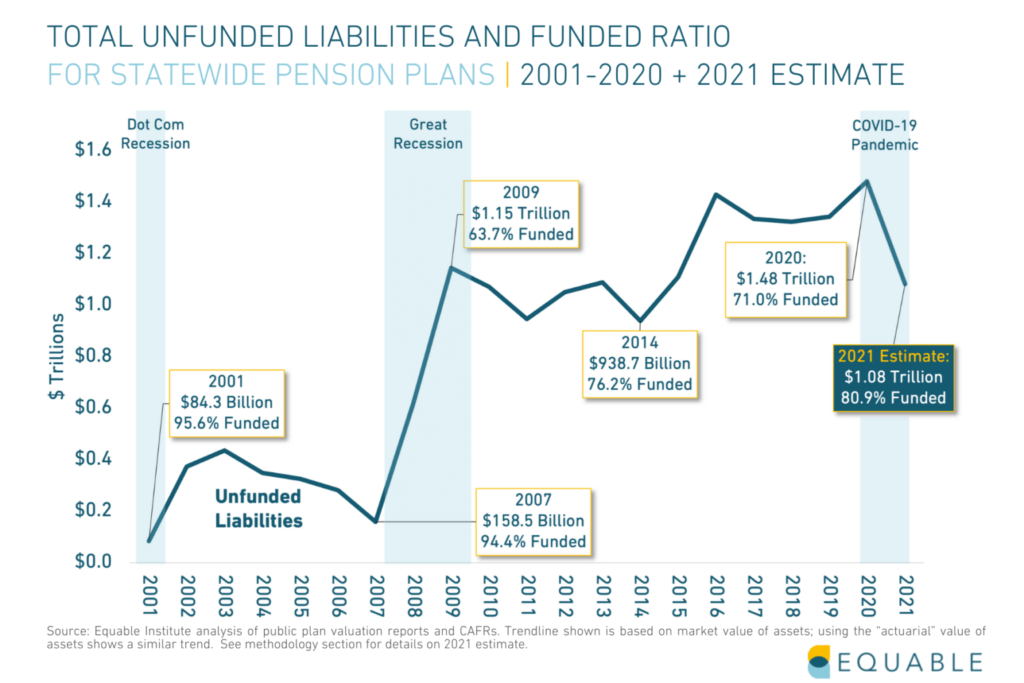

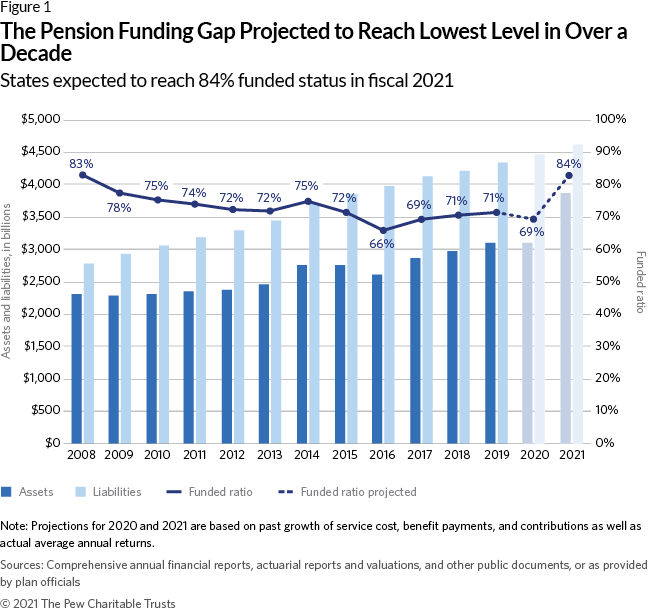

Underfunded pensions and the hunt for yield

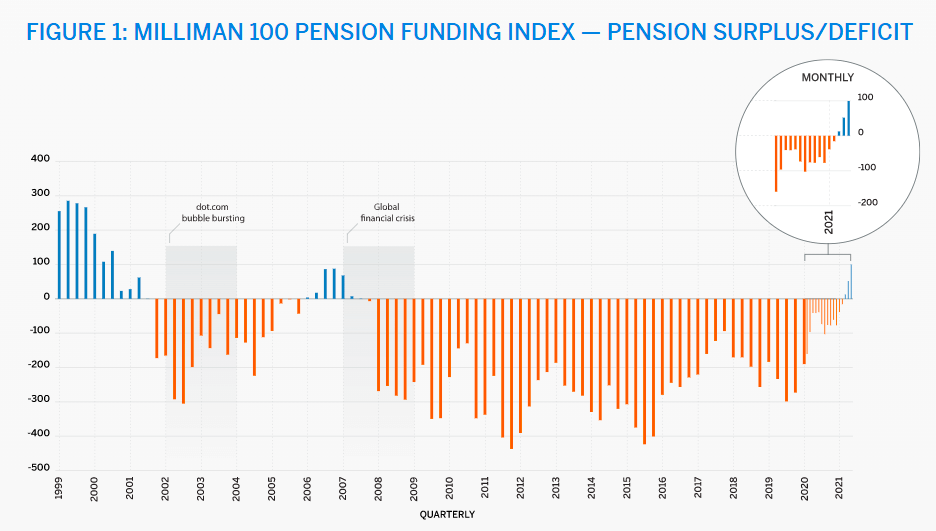

The other important factor that led to the explosive growth of venture capital was a hunt for yield. The growth of venture capital coincides with a dramatic increase in underfunded pensions1,2,3 around the world. These images give you a sense of public and corporate pension in the US, but it’s the same around the world.

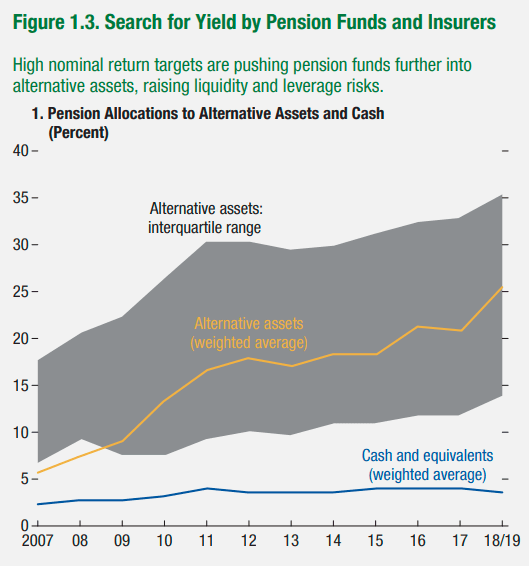

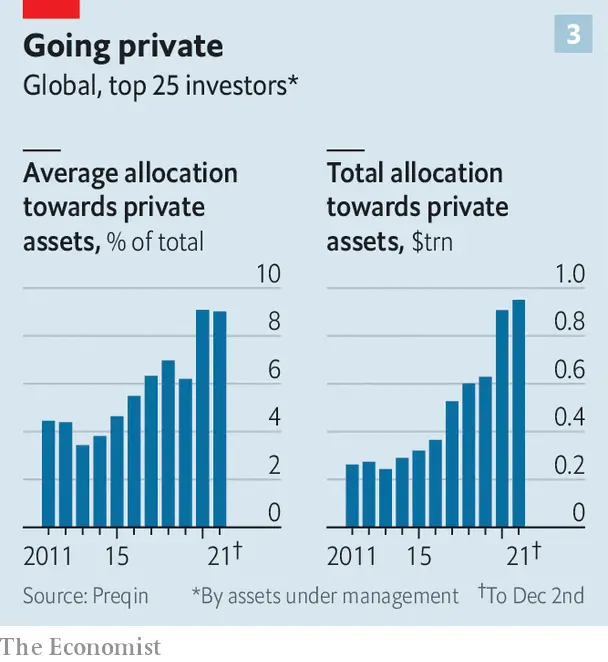

For a long time, US pensions and endowments had a returns assumption of 8-10%. This made sense at a time when treasury yields were high. But bond yields had been in a secular decline for well over two decades across the world. At the same time, pension liabilities have increased steadily. Pensions need to hit a certain return target to meet the liabilities, or they go bust. As bond yields fell, pensions had to supplement the returns. In order to hit their targeted returns, pension funds have substantially increased their allocation to alternatives such as venture capital, private equity, infrastructure and real estate over the last two decades. The average US pension allocation to private markets went from about 5% in 2000 to over 15% today. It seems like a small number, but pensions manage trillions. Even a 1% change in allocation means billions in flows.

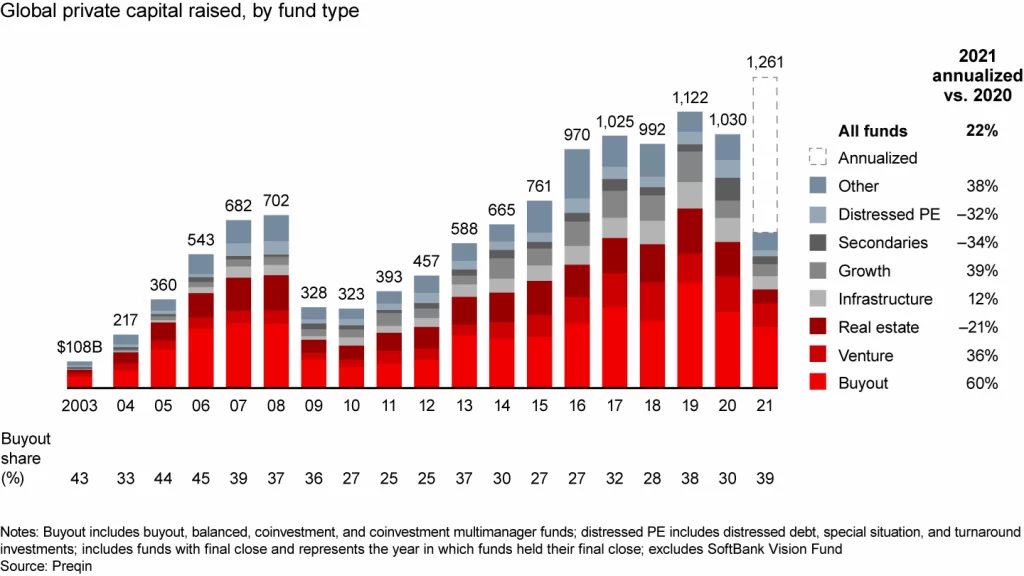

It’s not just pensions—endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and family offices have also dramatically ratcheted up private market exposure. This is the biggest reason behind the dramatic increase in funds raised by private equity and venture capital.

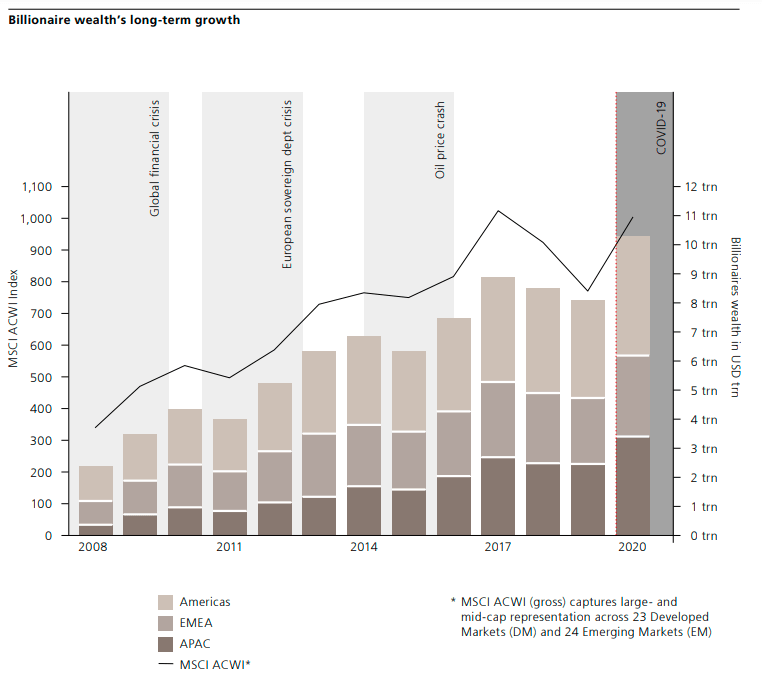

Richie rich 🤑

Over the last decade, the number of billionaires around the world has increased dramatically. These people combined control trillions in wealth. Along with the existing rich people that inherited generational wealth, the newly minted billionaires over the last decade control substantial wealth. Rich people typically operate in family office structures because it has fewer regulatory hassles than other structures. From being sleepy outfits, family offices are now twice the size of hedge funds.

Given the sizable pool of money, they’ve become serious players in the financial markets. We saw this first hand with the spectacular implosion of Bill Hwang’s Archegos.

Inevitably, this wealth has also flown into venture capital and private equity. The typical family office allocation to private markets ranges from 10% to 25%. Family offices are also increasingly becoming sophisticated, employing some of the best and brightest talent. They can go toe to toe with established VC outfits for deals.

Old players, new playbook

Interestingly enough, US mutual funds1,2,3 have been the other source of venture capital funding. Though their allocations aren’t as large as pensions, it’s nonetheless an interesting trend highlighting the rise of private markets. Names such as Fidelity, BlackRock, and T. Rowe now routinely appear in startup funding announcements.

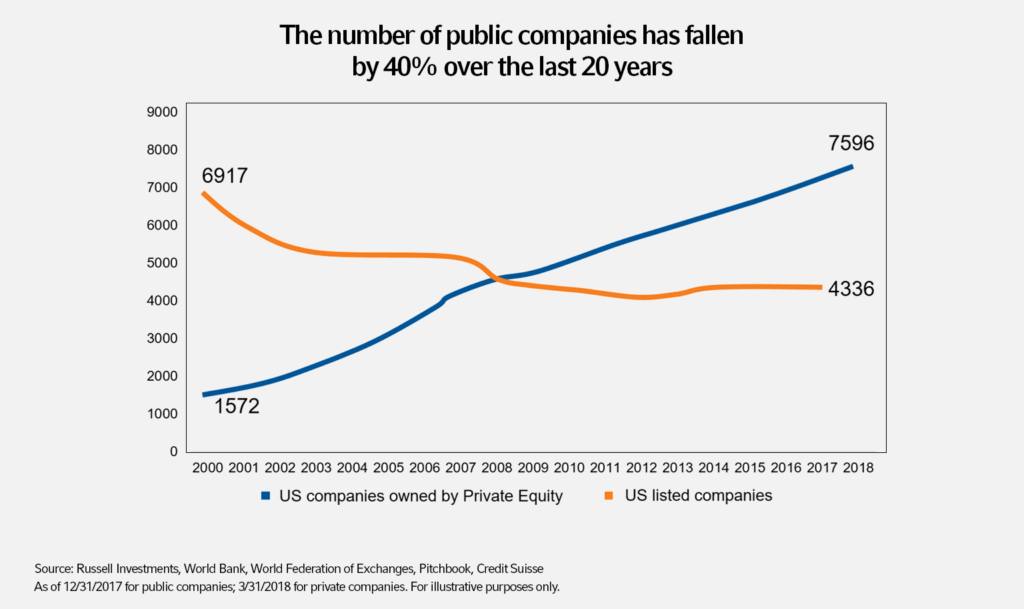

These factors, in turn, have created a feedback loop, and companies stayed private for longer as capital was available abundantly. Until the last couple of years, the number of US IPOs had almost dried up. The perceived shrinking of the opportunity set in public markets has been a significant driver of the growth of venture capital.

As an aside, private equity (PE) investors buy large and mature firms, “fix them” and try to sell them at a profit. Venture capital investors, on the other hand, invest in the early and growth stages of startups. But this definition no longer applies as the lines between PE and VC are blurring by the day. I'll explain why as we go along.

Rising from the shadows

Most importantly, the rise of private equity and venture capital should also be seen through the lens of the growth of shadow banking. Although the term “shadow banking” sounds foreboding, it’s just an umbrella term for non-bank firms that engage in banking activities like lending etc. Broadly speaking, entities such as private equity, private credit, hedge funds, money market funds, asset managers, insurance companies, securitization vehicles and broker-dealers fall under the umbrella. Shadow banking came into the spotlight during 2008 when people discovered that money market funds, prime brokers, repo dealers, and securitization vehicles were at the heart of the crisis.

After 2008, regulators in advanced economies woke up and tightened the screws on banks by increasing capital requirements, passing new regulations and oversight. Steadily, banks retreated from many lending and trading activities in the post-2008 period. At the same time, institutional pools of money from pensions, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and family offices grew larger than ever. They were hungry for yield, given the low interest rates.

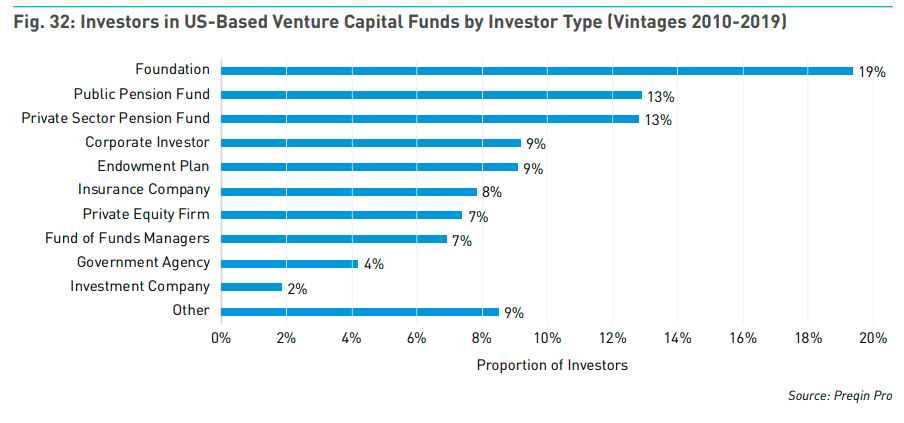

Here are the biggest limited partners (LPs) in the US.

The eye-popping growth of private equity and venture was also a result of two factors: the shrinking bank lending after 2008 and the rise of large institutional investors. PE and VC firms stepped in to intermediate the flow of money from institutional investors to private markets through various forms of equity and debt.

Today, private equity firms have emerged as the biggest lenders to companies in many segments that banks don’t serve anymore. Specialized firms called venture debt firms have also emerged to provide credit to startups looking for alternatives to equity financing. Of course, all this isn’t without risks. Shadow banking entities have lesser linkages to the banking system but can still cause serious mayhem.

We saw a first-hand demonstration when IL&FS declared bankruptcy in 2017 and caused the Indian bond markets to freeze. We saw an even bigger demonstration during the COVID-19 crash of 2020. The investor rush to cash or dash for cash led to severe strains in treasury markets, corporate bond markets, bond funds, REITs, mortgage-backed securities and bond dealers in the US, UK and Europe. It started with the massive selling of bonds and equities as people increased their cash levels. The large-scale selling led to falling yields on bonds. This split over to hedge funds and other leverage actors who started getting hit with margin calls leading to forced liquidations, further intensifying the selling pressure, and severely degrading the market.

Heightened redemptions led to a run on money market funds, much like in 2008. Selling pressure in corporate bonds led to widening spreads, and large parts of markets froze. This stress spread to bond funds and ETFs. Bond ETFs were trading at substantial discounts compared to the same bond funds. If not for the significant intervention by the central banks across treasury markets, repo markets and corporate bonds markets (through corporate bond ETFs), these markets would’ve quite literally snapped like a twig. Shadow banking entities were at the heart of these dislocations. For many, the next big crisis lurks in private markets and shadow banks. It’s not hard to see why.

Ok, all that’s well and good. But why are we looking at this US-centric version of private markets history?

The US exports 3 crucial things:

1. Trash – both actual trash and white trash.

2. Treasuries – US treasuries are the preferred safe asset for both governments and the private sector. So, it manufactures and exports US Govt bonds.

3. Venture capital – Given the depth of its institutional capital pools, it’s also the world’s largest exporter of venture capital, accounting for well over half of global venture capital. The story of the growth of venture capital and private markets is a US story because it underwrote most of it.

Now, back to the main point, why did the private markets grow so large? Well, people will quickly jump up like they have a lizard on their neck and tell you that it was the central banks, low interest rates and “money printing.” Sure, these were secondary factors, but not the primary causes. The growth of the venture capital and private markets has been in the making for well over 4 decades. Things rarely happen overnight. The structural changes that create or destroy trends take decades to form and mature. But who cares about nuance?

Prelude to the end

VCs bet on unproven ideas and companies—a certain amount of irrationality is baked into the model. The default mental model that most people use to think about venture capital is to compare it to public markets investing—I don’t think that necessarily works. But one aspect where venture capital and public markets are similar is that both are super-hit businesses. A small number of winners will deliver outsized gains and pay for the rest of the duds.

Given the informational asymmetries and the asymmetric payoffs in private markets, investing bets aren’t just based on available data but a bit of irrational optimism. But much like public market cycles, every VC cycle starts with some semblance of sanity and ends with utter insanity. I think the tail end of the current cycle—which seems like it’s over—feels much crazier than the dot-com madness, or at least on par with it.

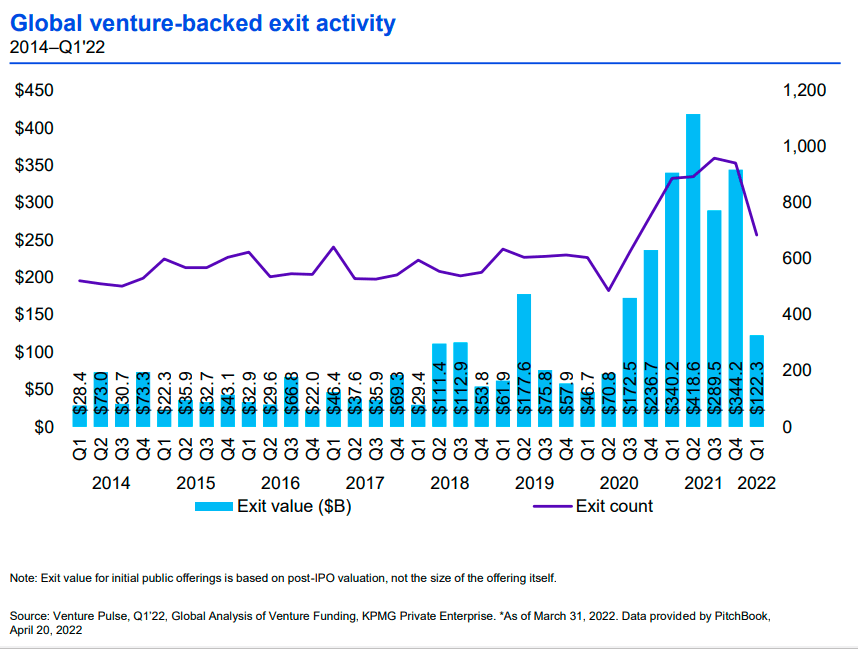

Over the years, the flood of capital in venture capital has also caused some serious FOMO and returns chasing among VC funds. In the later stages of a cycle, investments aren’t driven by reasonable theses, but FOMO. The flood of capital into fads and frauds in crypto over the last 3 years is a prime example of this. With so much money chasing so few companies, we’ve had a record number of deals, a dramatic increase in funds raised and deployed, record exits, and moon-high valuations.

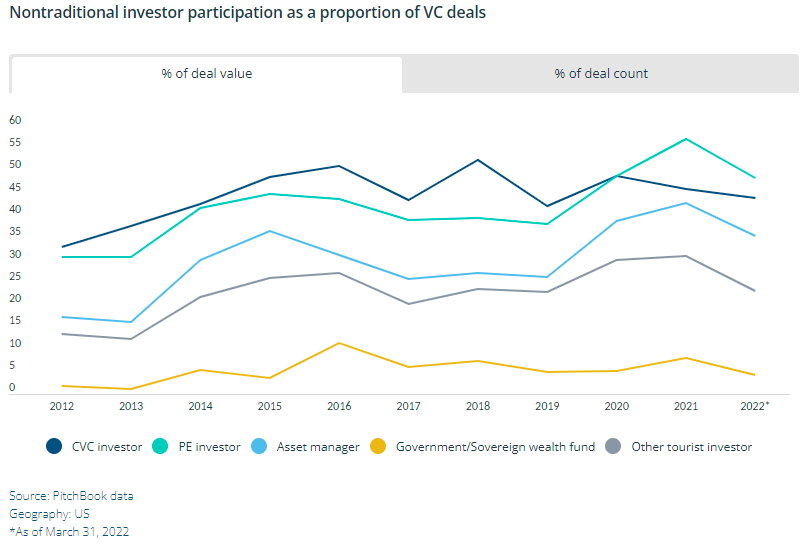

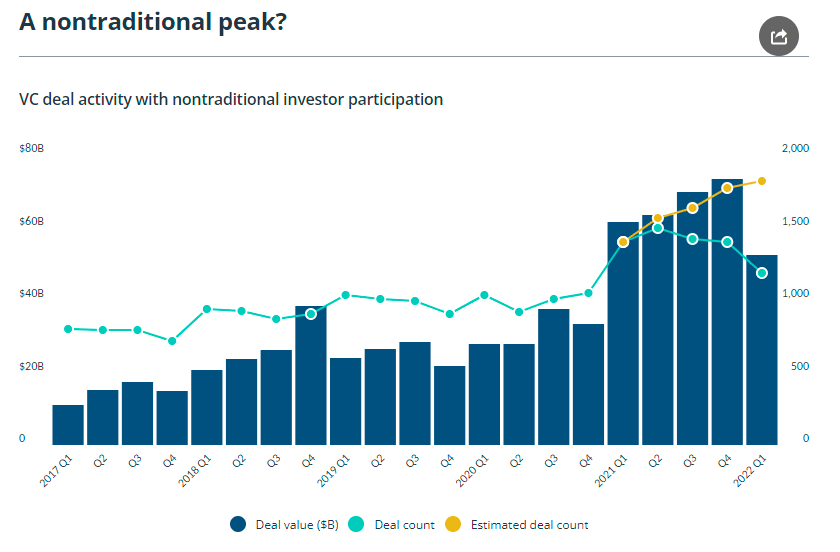

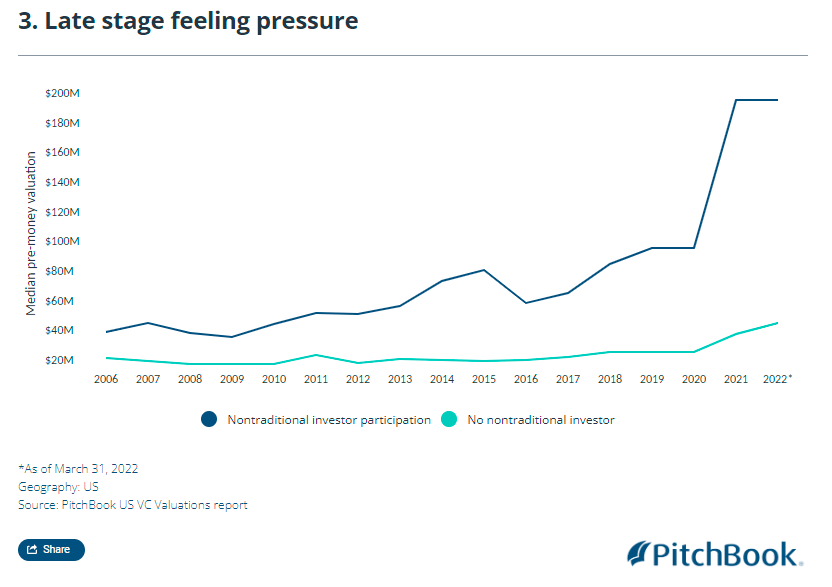

All the lines started sloping upward sharply around 2019, and the 3 ensuing years were the craziest part of this cycle. This was partly driven by the entry of non-traditional investors like Tiger, D1, corporate venture funds and mutual funds. These investors tend to be less price-sensitive than traditional VC firms and a lot faster in closing deals than traditional VCs.

The great detox

Things were looking good until non-transitory inflation finally showed up. Central bankers who had been chilling for the past decade woke up suddenly and started hiking rates—something they had forgotten how to do. Since the start of the year, the US markets, especially the tech and growthy segments of the markets, have taken a brutal knock. It doesn’t look like the bloodletting is done yet.

The crazy multiples these stocks used to command have shrunk quite a bit in a short span of time. Analysts that had discounted cash flows of 2097 are opening the Excel sheets and changing the dates.

All the worthless companies that IPO’d in the last few years have been infected with gravity.

It’s a bittersweet moment for VCs. Given the mindless appetite for growthiness in the last few years, VCs had a record number of exits. But they are still stuck with plenty of private companies in their portfolios whose values are falling fast.

One of the advantages of private markets is that investments don’t need to be marked to market. This allows VCs, pensions, endowments and other large private market investors to show artificially inflated returns when compared to public market equivalents. Cliff Asness of AQR calls this “volatility laundering.” VCs often use this to raise new funds. In theory, the lack of mark to market accounting in private markets was supposed to solve the short-termism that plagues the public markets. But on the flip side, VCs don’t have an incentive to quickly mark down their investments even when public market equivalent stocks are down 50%+ as they are now.

Adding private investments is even more helpful for crossover funds like Tiger. Since private investments aren’t marked to market, they don’t fall as quickly as public market investments. This lag allows crossover funds to window dress their returns to show lower losses when their public markets investments tank. Tiger is apparently down 50% YTD. The image would be far worse if all their private investments were marked down to reflect public market realities.

Tiger’s write-downs of its startup bets in its venture and stock-picking funds have been modest thus far compared with its public holdings, people familiar with Tiger’s numbers said. But a venture fund’s performance often lags behind drops in public markets. Private companies are harder to value, and managers often rely on a company’s valuation at a prior fundraising round. Early this year, Tiger told investors the $2.3 billion it invested across numerous funds in ByteDance was worth about $6.4 billion—a huge win. But since, it has written down its stake by over $2 billion, estimating ByteDance’s valuation at less than $300 billion, people familiar with the numbers said.

Highflying Tiger Global Humbled by Unraveling of Giant Tech Bet

This is why private markets tend to lag public markets by 6+ months. VC funding has only dropped marginally, and the number of down rounds hasn’t picked up yet. But this is due to the great private markets mirage. If the public markets continue their downtrend over the next few months, we’ll see markdowns. Private markets don’t adjust to the public market realities easily. They always come kicking and screaming, but they will come.

Things are so bad that VCs are sending memos with filthy words like “sustainability”, “profitability”, and “be alive.” The startup community should strongly condemn such language.

Sequoia wants startups to adapt and even published a memo titled “adapting to endure.” Lightspeed declared, “the boom times of the last decade are unambiguously over” in a post titled “the upside of a downturn.” In a CNBC-styled memo, Y Combinator asked startups to reach a state of “default alive.”

The head of Sequoia India keeps forgetting that he is a VC and uses the F word every few months.

This tweet sums up the dramatic shift in sentiment.

Though private markets time to come back to reality, we’re already seeing the damage:

- Term sheets are getting pulled, and deals are being renegotiated with investor-friendly terms that had gone out of fashion.

- IPOs are done.

- Deals on private markets exchange Carta were down 38% in Q1.

- Over 17000 employees have been laid off by tech companies globally, and startups are cancelling offer letters. 9500+ people have been laid off in India alone.

- Fidelity has marked down several of its holdings by 13-50%.

- Private companies like Klarna, Chime, FTX and GoPuff are trading anywhere between 20-70% lower in private markets.

- Series A rounds have been cut in half.

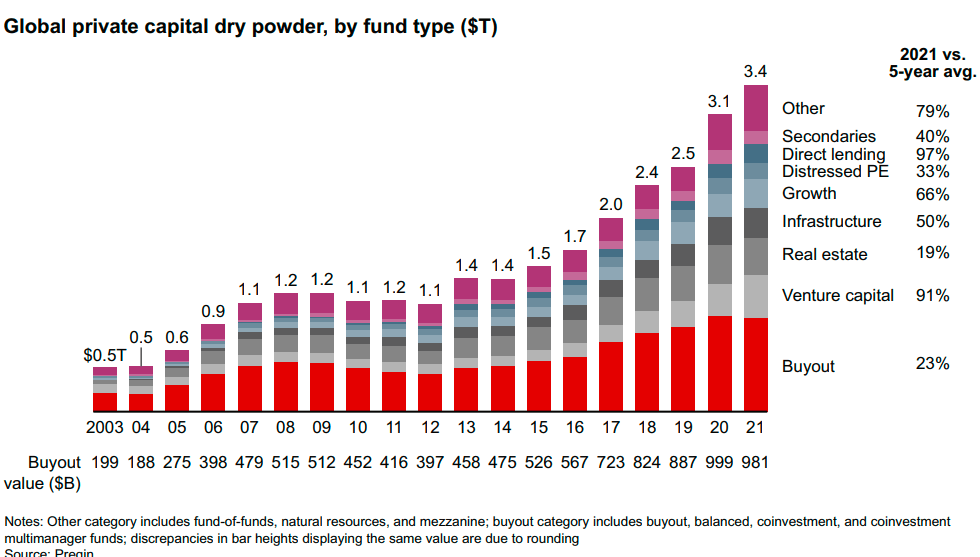

The one thing I keep hearing is that there’s a lot of money on the sidelines. In some sense, it is true, given that venture funds had record distributions in the last 3 years. All of this money has to be put to work somewhere. So, does this mean that even if the public markets tank, venture activity won’t fall as badly as it could have in the absence of this dry powder? I don’t know.

This Bain report put the total private markets dry powder at $3.4 trillion. Pitchbook estimates $222 billion of this dry power in venture capital alone, while Prequin puts it at $478 billion. But not all of this capital will be called by the VC funds and deployed. More importantly, if this market crash becomes as bad as 2008 or 2020, limited partners may default even if the capital is called.

More craziness?

Venture capital and private equity aren’t the only crazy segments of the private markets.

“Some parts of private equity look like a pyramid scheme in a way,” Amundi Asset Management’s chief investment officer Vincent Mortier said in a presentation on Wednesday. “You know you can sell [assets] to another private equity firm for 20 or 30 times earnings. That’s why you can talk about a Ponzi. It’s a circular thing.” “Just because there’s no mark to market doesn’t mean there’s no risk,” said Mortier. “There are some very, very good opportunities, but there are no miracles. Eventually there will be casualties, but that might not be for three, four or five years.”

FT

- Since 2008, there’s been dramatic growth in leveraged loans. Over 90% of leveraged loans are the so-called covenant-lite loans. These loans have very minimal lender protections.

- Global junk bond issuance has been making new highs since 2008. But rising interest rates are kryptonite for high-yield issuers.

- Direct lending by private equity has seen dramatic growth.

These are just some things at the top of my head—there’s a lot of craziness in other pockets of the market. But given the brutality of the markets so far, the bubbles are popping faster than they formed. But we’re in for some fascinating times.

Remember that old Chinese guy who said, “may you live in interesting times”? I hope he died a miserable death.

Leftovers

This might sound lame, but as I was writing this post, I couldn’t help but wonder about the sheer amount of research that’s available for free. Even if you want to learn about some weird and arcane corner of the markets, you’ll find a ton of resources. I thought I’d highlight a few amazing papers, videos and podcasts I discovered as I was writing this.

None of what I’ve written is original. It’s just a quick summary based on the amazing work done by academics, researchers, and journalists. Most of what I know about the 2008 crisis is based on Adam Tooze’s Crashed, and the amazing research by Neil Fligstein1,2, Darrel Duffie, Gary Gorton and Andrew Metrik.

In November 2008, Queen Elizabeth, visiting the London School of Economics, asked the economists why did no one see it coming? Andrew Hindmoor Allan Mcconnell had a brilliant paper looking at the messiness of heeding the warnings about crises in real time.

The other paper that stood out for me was Fifty Shades of QE by Brian Fabo, Martina Jančoková, Elisabeth Kempf and Ľuboš Pástor. Just like gravity makes the Earth orbit the sun, incentives are by far the most powerful force that moves people. This paper is a masterclass on the power of incentives.

I’m a little embarrassed that I didn’t know about Viral Acharya until he became the deputy governor of RBI. His body of research is insane, especially his analyses of the 2008 crisis. I learned a tremendous amount from reading his papers.

Two other names that kept coming up as I read more about the crisis were Perry Mehrling and Markus Brunnermeier. Again, I’m embarrassed that I didn’t know of them before. That stupid econ class in my MBA was an utter waste.

Most people don’t appreciate the research published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). It’s a veritable goldmine of all things finance and markets. The bulletins and quarterly reviews are particularly informative. This paper should be mandatory reading for anyone interested in learning about the crisis.

Similarly, VoxEU is another amazing portal for economics research.

Until I started writing this post, I hadn’t appreciated just how important shadow banking entities like money market funds, repo dealers and private equity firms are. Daniela Gabor is a leading expert on shadow banking, and her research is bloody amazing1,2,3. She is also a must follow on Twitter, and her videos are incredibly insightful. In a similar vein, Zoltan Pozar’s notes on US repo markets and papers are mandatory reading.

Andy Haldane’s The age of asset management? speech way back in 2014 was really prescient. It foreshadowed the loud debate about the power wielded by modern asset managers, who are now the biggest owners of large swathes of public markets.

Leave a Reply