“Good times become good memories, but bad times become good lessons.”

Uncle Iroh, Avatar: The Last Airbender.

What a crazy decade the 2010s were!

The tide of cheap money deluded an entire generation into thinking they were geniuses.

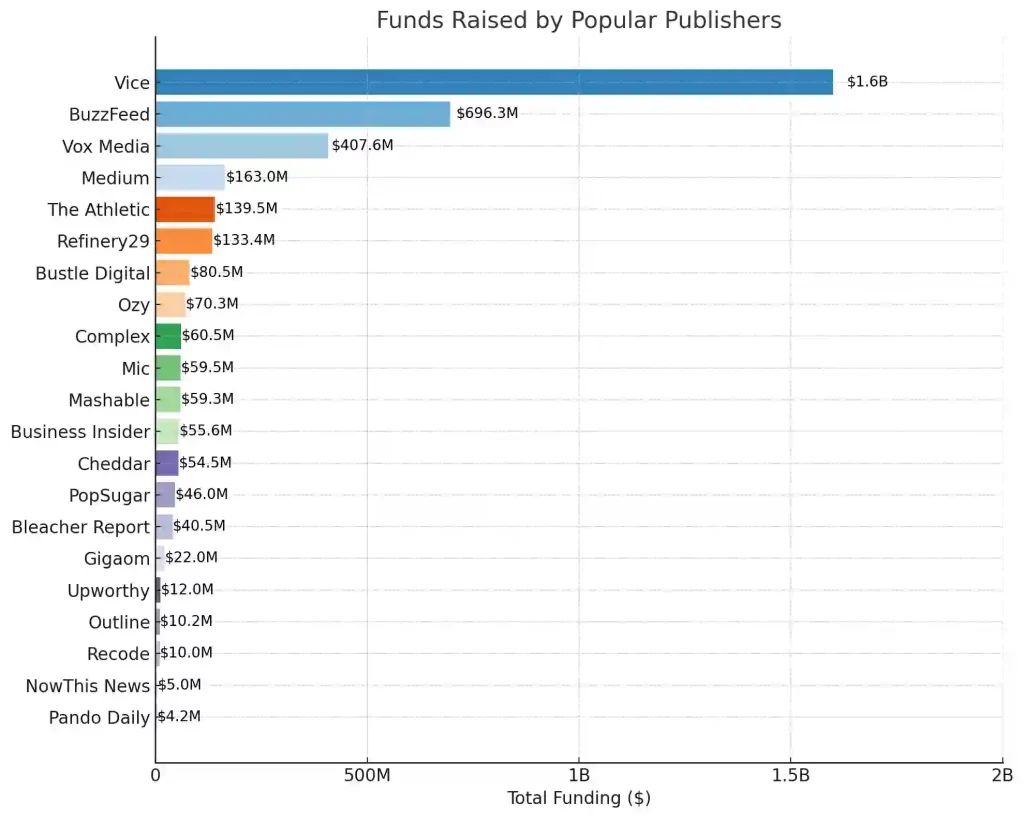

Everything worked until 2022. You could raise $130 million for a $400 juicer (Juicero), $1.75 billion for a mobile app that only has 10-minute shows (Quibi), $700 million for a cat picture website (BuzzFeed), or $360 million for a dog-walking startup (Wag). If you went to SoftBank or Tiger with an idea about an app that analyzes farts and tells what flower or vegetable they smell like, you’d be assaulted with a $100 million cheque—FSaaS: fart smelling as a service.

But just like peach-scented farts don’t linger forever, the good times don’t last. As interest rates around the world remain high, things are unraveling.

The good times are over.

They were too good to be true.

Now that the tide has receded, it turns out the geniuses were swimming naked. The geniuses are now trying to convince the world that their nakedness was a deliberate fashion choice.

It turns out, many of the supposedly radically innovative businesses built by galaxy-brained geniuses were just fleeting farts. They were all Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) babies. It wasn’t brains; it was a bull market.

Cue Green Day – Boulevard of Broken Dreams.

I walk a lonely road, the only one that I have ever known. I don’t know where it goes, but it’s home to me and I walk alone.

I walk this empty street, on the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, where the city sleeps and I’m the only one, and I walk alone.

Geniuses turned out to be frauds, and dreams turned out to be delusions. You know things are bad when VCs start uttering the term “forensic audit.” After a decade of crazy partying, it’s time for a detox.

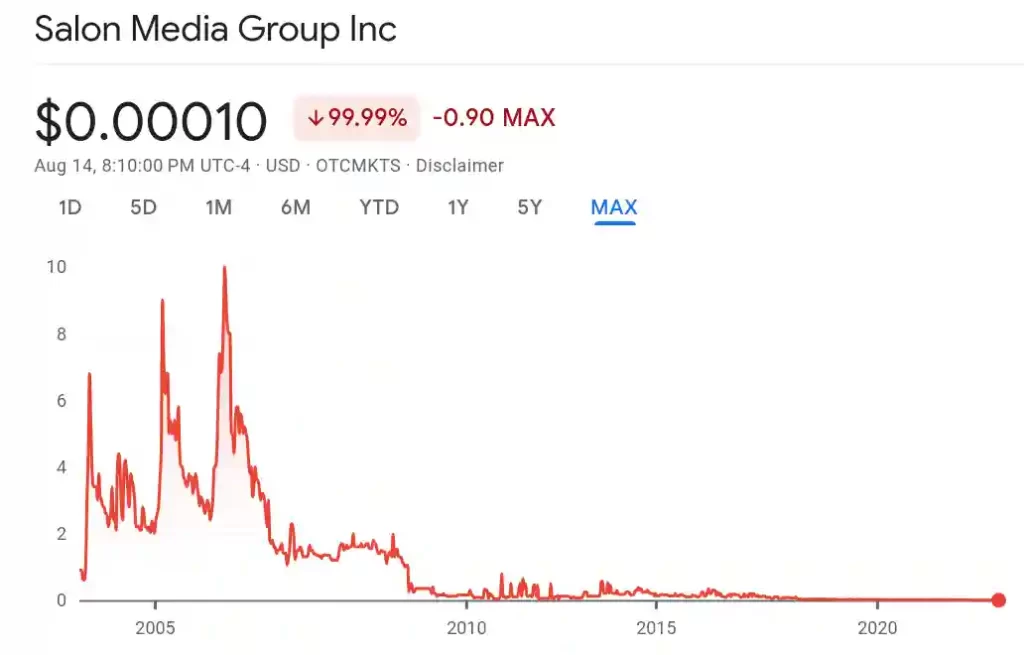

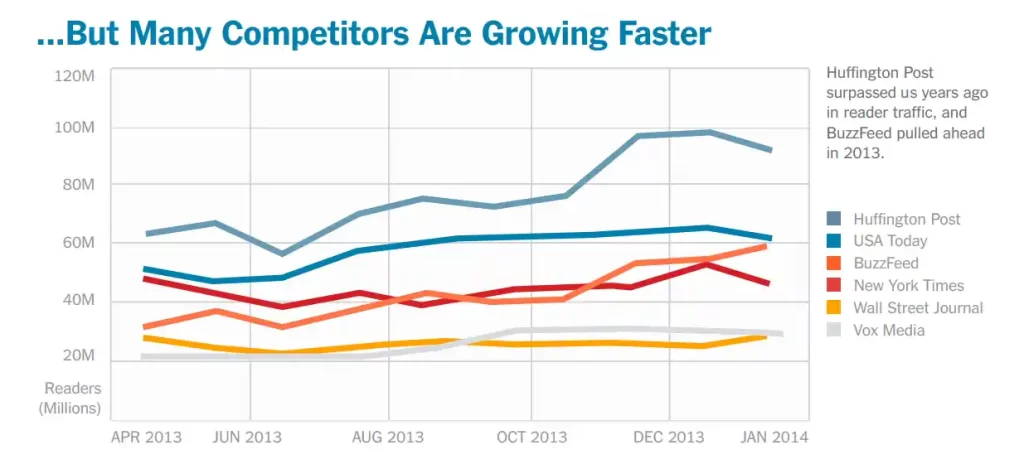

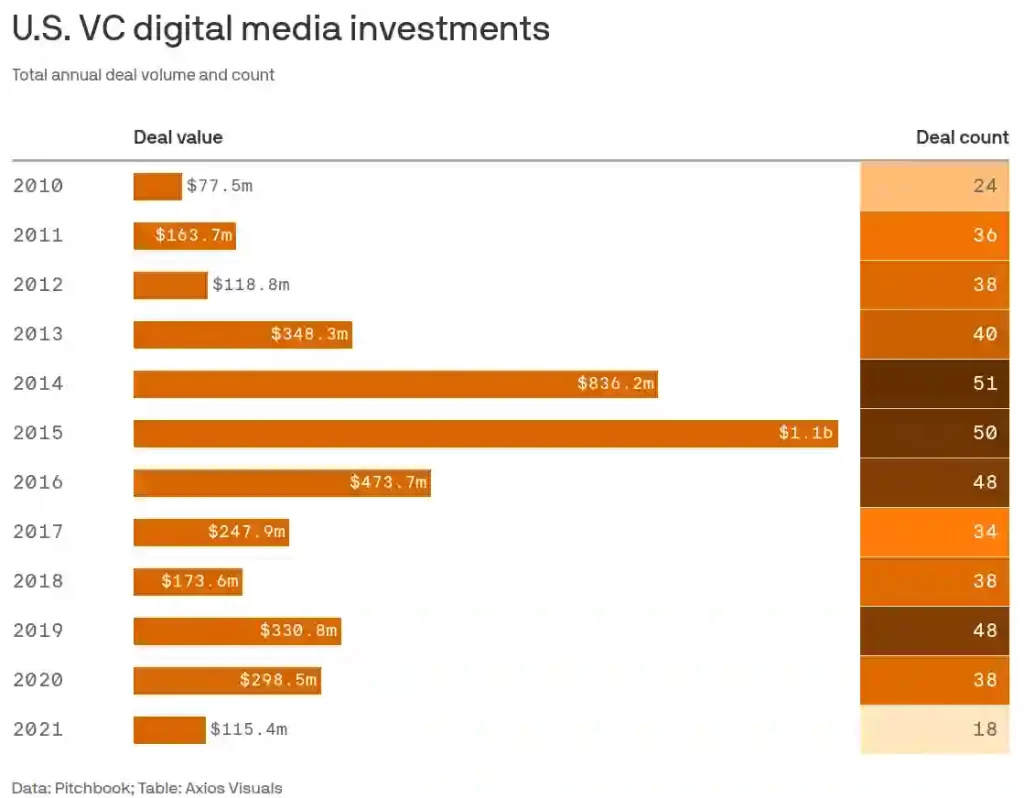

The latest casualties are from digital media, an industry I have passionately followed for over a decade. A few months ago, BuzzFeed shut down BuzzFeed News, and Vice Media filed for bankruptcy. If you rewind back to 2010, these digital upstarts were supposed to be the future. They were set to euthanize legacy media companies like The New York Times, CNN, and Disney and drag the industry into the 21st century.

It all seemed so romantic.

The death of the companies has inspired countless think pieces, postmortems, and obituaries—it’s the “end of an era,” and there’s a “regime change.” Such a charade isn’t complete without derivative thunk pieces of the think pieces feigning surprise and shock. How could the digital saviors that were supposed to deliver the news publishing industry from certain damnation die?

Vice and BuzzFeed News are just the poster children for the ills that plague digital publishers. Almost all publishers are buggered to various degrees.

Why did they die? Could the death have been avoidable? Why does the media business suck? Were the deaths of these digital news media outlets a surprise?

I have answers to everything!

Before I answer the questions, let me give you some background. You don’t care about it, but I will just the same.

Flashback

I belong to a minority that still believes that a free and independent press is the difference between a thriving democracy and a banana republic.

“Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets.” ― Napoleon Bonaparte

I know that’s a quaint notion at a time when the term “mainstream media” has become a pejorative. At its best, good journalism holds the powerful accountable. It gives us all a voice. It lifts the veil of our ignorance and makes us less stupid. The key terms here are “at its best” and “good journalism.” By no stretch of the imagination is our media always at its best. But when it is, we are all better off.

My dad read newspapers every day and I picked up the same habit. As far as I can remember, I’ve always read random things. My dad’s family didn’t appreciate the value of education. I still remember him telling me stories about how some asshole family members of his made it impossible for him to pursue his studies. Given his experiences, he made it a priority to get me and my brother to read and interact with others as much as possible. Tagging along with him on his Bajaj Chetak and Kawasaki Bajaj KB 100 to the local tea shop to meet his friends was a regular ritual.

No matter what changed as I grew up, the one thing that remained a constant was we always had newspapers. Whenever we changed houses, my dad would hunt down a newspaper agent like Liam Neeson In Taken and restart the newspaper subscription. Reading a newspaper became a daily habit from an early age. I understood very little but read them nonetheless. With time, I understood the value of newspapers.

This is how weird I was. When DNA launched in Bangalore, they had salespeople selling subscriptions. I still remember tagging along with the sales guys and helping them sell subscriptions in my neighborhood.

Over time, I started writing as well, but I was shit at it, really shit. I can’t recall why, but I also wanted to be a journalist at one point. Thank God I didn’t become one. If I had, I would be sharing a luxurious single-bedroom condominium made of zinc-aluminum sheets with migrant construction workers from Bihar on a construction site at Whitefield.

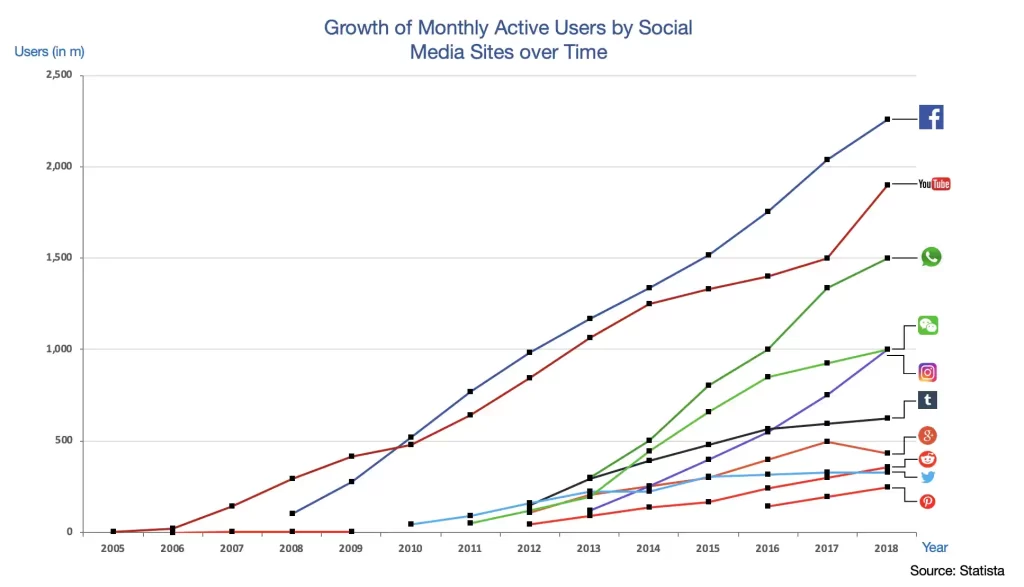

I have no idea why, but I started following the news publishing industry around 2013–14. It was the early days of social media in India, and people were poking (not that poking) each other on Facebook. Blogging was still cool, saying the term “RSS feed” out loud didn’t evoke geriatric sympathies, publishers like BuzzFeed and its clones like ScoopWhoop were starting to take off, and the internet hadn’t yet become the public toilet it is today. Torrents were a thing, with boner pill ads popping from the bottom right corner.

Ok, I’m done reminiscing. This Kannada serial-style flashback was to say that I’ve been following digital news publishing for a long time. I had stopped following the industry around 2019. The death of BuzzFeed, Vice, and the massive layoffs elsewhere rekindled my interest in the industry. For the past couple of months, I’ve been reading, watching, and listening to anything I could find about the industry. So I figured I might as well write about it.

Why?

Because I’m on the interweb and I have a blog. So clearly, I’m an expert on all things under the sun, and I must subject the world to my expertise. Them’s the rules.

I start the post with a quick history of American and European media. This isn’t a detailed history but just the key events in the evolution of news and newspapers to give you a 90,000-foot view.

Since the American media market is the largest in the world, with the richest consumers and a news publishing industry that’s in terminal decline, I trace the growth and decline of the American news publishing industry. I tell the story through the eyes of people in the industry, observers, scholars, and my own observations. In a sense, this is as much a curation of thoughts, views, and experiences of people in media as it’s my own opinion.

Jump around

- A broad history of news and newspapers

- History of American newspapers

- Did the internet kill newspapers?

- Unbundling of the newspaper

- Newspapers in the internet era

- Do people care about the news?

- News publishers and the dot-com bubble

- News in the era of social media

- Dancing to Facebook’s tunes

- Pivot to video

- The end of good times for digital publishers

- The original sin

- Where are we now?

- Extortion rackets

- Welcome back to reality

- Is it all doom and gloom?

- Peeping into the future

- Why write this post?

Once upon a time…

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. —George Santayana

It’s always easy to say something was obvious in hindsight, and it almost never is, with the exception of the news publishing industry.

I’ve got news for Mr. Santayana: we’re doomed to repeat the past no matter what. That’s what it is to be alive. ― Kurt Vonnegut

The troubles facing digital media outlets aren’t new. The news business has always sucked, and the script is the same as traditional newspapers—hubris, myopia, and a lack of basic economic sense. Why and how did we end up in a place where we talk about news publishers as if they’re terminal patients? You have to look to the past for answers.

As Mark Twain famously never said:

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

I’m not an archaeologist in the formal sense of the word—I don’t have any education or expertise. But when you think about it, archaeology is just digging up dirt, finding weird rocks, and making up stories about them because finding 800-year-old people is hard. So, anybody who has ever dug up dirt is an archaeologist. I was a notorious dirt digger when I was young. Furthermore, I am amazing at Googling, aka digital dirt. So, I’m an archaeologist and, by extension, a historian.

Before the written word, news was transmitted through the spoken word. Messengers and town criers were the earliest newspapers but human. Government bulletins were the precursors to modern newspapers and can be traced back thousands of years.

But if you believe in made-up things like history and evidence, one of the first newspapers can be traced back to Rome between 59 BC and 130 BC. Thanks to Julius Caesar, the Roman Empire had daily gazettes called Acta Diurna, or daily events. These bulletins contained news about births, deaths, gladiatorial fights, astrology, court trials, etc. There was a separate bulletin called Acta Senatus to report on the developments of the Roman Senate. In a way, this was the very first Twitter feed. The Han dynasty may have had Dibao, or palace reports, as early as 206 BC. Around 713–734 AD, in the Kaiyuan era, the Chinese had something called Kai Yuan Za Bao, or Bulletin of the Court. These bulletins were handwritten on silk and contained domestic and political news for government officials.

The modern, regularly published newspapers as we know them were not possible until the invention of the movable-type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440. Although Gutenberg gets all the credit, printing presses existed long before him. The Chinese and Japanese had woodblock printing as far back as the 7th and 8th centuries, and the Koreans had it in the 10th and 11th centuries. The Chinese had the movable-type printing press around 1040 AD, and the Koreans had it by 1230. They never caught on in China because, unlike English, the Chinese language has thousands of characters, and having a printing block for every character was impractical.

While it’s easy to write about the history of news in a neat sequential order, the evolution of news was anything but. It’s messy, chaotic, and unpredictable. To give an example, soon after the invention of the Gutenberg press, one of the earliest things to have been published was erotica:

Among the early books printed on a Gutenberg press was a 16th-century collection of sex positions based on the sonnets of the man considered the first pornographer, Aretino—a book banned by the pope.

Soon, the printing press started spreading around Europe. In 1470, a poem describing the conquest of Negroponte by the Ottomans was published in Milan. Around the 1500s, Italy had handwritten and printed newsletters called avvissi. The avvissi were circulated both in public and private. They aggregated diplomatic, military, political, and religious news from various sources. By the 1570s, they were widely read by the city elite in Rome and Venice. The Medici dynasty invested considerable resources in setting up an information-gathering network throughout Europe to collect intelligence. Cosimo I de’ Medici created a postal network when he ascended the throne to send and receive avvisi.

Between the 1500s and 1660s, the Fugger family, one of the richest in Europe, established a vast network of correspondents to collect news in the form of handwritten newsletters. These newsletters contained political, military, religious, and criminal news. Apart from having a near monopoly in copper, the Fuggers were one of the largest lenders and were bankers to merchants, princes, popes, kings, and emperors. There’s speculation that they set up a news correspondent network to decide their lending rates. There’s debate over whether these were private newsletters or if they were circulated publicly, but it looks like they might have been public. In a way, the Fugger news network preceded finance news as we know it.

Fuggers are the richest family you have never heard of, with a reported net worth of over $400 billion.

There’s debate over what’s considered the first newspaper, but Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien (Account of All Distinguished and Commemorable News), published in Strasbourg by Johann Carolus may have been the first European newspaper. Some consider this a “newsbook” and not a newspaper. The Courante uyt Italien, Duytslandt, &c., was the first broadsheet Dutch newspaper and was published in Amsterdam in 1618.

The Star Chamber Decree of 1586, under the reign of Elizabeth I, imposed restrictions on the publication of news in England. Early news publications in England were called corantos, and were printed in Amsterdam. The first coranto printed in England may have been The New Tydings Out of Italie Are Not yet Come in 1620 by Thomas Archer. This news sheet described the Thirty Years War. Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, published in 1690 by Benjamin Harris was the first colonial newspaper in America. The paper was immediately shut down by the governor of Massachusetts, and Harris was jailed.

The Boston News-Letter and The Boston Gazette launched 14 and 15 years later, respectively, and these papers avoided politics. In 1721, James Franklin, the elder brother of Benjamin Franklin, started The New England Courant in Boston without a license. The paper opposed the British from the start, and this landed James in jail multiple times. After a couple of years, the British colonial authorities prohibited him from publishing, and he handed over the publishing of the paper to Ben Franklin to get around the restriction. The New England Courant set the template for a free and independent press.

The colonial era newspapers were small operations with six to twelve people. Most towns had one printing operation run by a master printer who owned the printing press. Setting up a printing press was a costly affair. Despite the printing press being a simple wooden contraption, it had some iron parts, like the screw, but America didn’t have the manufacturing capabilities. The screw and the type had to be imported from England. The type was more expensive than the screw.

The master printer did everything from the manual work of setting type to editing and financing the operation. These roles would separate as newspapers evolved. The master printer would typically be assisted by his wife and would employ other journeymen, apprentices, and sometimes slaves. Since most towns couldn’t support multiple print operations, journeymen and apprentices moved to different places to set up shops, forming networks of printers who would collect, curate, and distribute news. These networks also developed and spread through marriages.

Colonial-era printers made most of their money from job printing or on-demand printing, like printing pamphlets, broadsides, etc. In fact, pre-revolution printing operations weren’t profitable and barely made enough to put food on the table. Printers published almanacs, speeches, and other political material to diversify away from only relying on newspapers.

Benjamin Franklin was a true pioneer of the newspaper business and was the most successful printer, thanks to his keen business sense. Here’s Joseph Adelman, the author of Revolutionary Networks, describing the savviness of Ben Franklin:

If you want type of any decent quality it really has to come from England that had to be imported so it’s an expense on its own and then it has to be imported which adds an expense. And so many printers when they’re first starting out will start out with a hand-me-down for lack of a better word set of type from a master or from someone in town who just died and they’re having an estate sale to get rid of that printers belongings. So you’ll buy to the cheap secondhand type that means that people are often seeking partnerships when they’re trying to start an office that could be with a former master.

That’s actually something Benjamin Franklin excels at, that’s part of what makes him such a success is he takes his own printing office and turns it into a training ground to send out printers to various other places. He retires himself from the printing trade in 1748 but well into the 1760s and even after the Revolution he’s got printing partnerships not only in Philadelphia where he had been but in New York in New Haven Connecticut in Maryland in Charleston South Carolina in a couple of different places in the Caribbean where he’s populating his former apprentices getting them out of Philadelphia so they can’t compete with him and then setting up partnerships where he pays to get them set up because he has that financial capability and then takes a share of the profits.

Benjamin Franklin was an avid ad-pitchman, using his sharp wit to craft ads for his customers. (One general was trying to convince citizens to donate horse carts to him; a Franklin-penned ad helped the general acquire over 200.) “He was the original ‘Mad Men,’” says Julie Hedgepeth Williams, a journalism professor at Samford University.

Clive Thompson/Smithsonian Magazine

Newspapers weren’t meant for the masses but rather for a small elite. Newspapers were supported by ads because most people didn’t pay for their subscriptions. 30–50% of the paper was dedicated to advertisements. Unpaid dues were such a problem that newspapers would print the names of people who hadn’t paid, begging them to pay or threatening to cancel the subscription. The advertisements were usually for runaway slaves, adultery, government notices, etc. Here’s an example:

Newspapers were produced really for a small, relatively elite audience, people middle class and above. Each issue contained advertisements, which usually took up a third to half of the total space. These could include merchants and vendors, government notices, and notices searching for runaways (which included servants, the enslaved, horses and other animals, and the occasional wife). The rest of the paper was devoted to political and commercial news from the British empire, in particular from London, other colonies, and a small section devoted to local news. — Joseph Adelman

Papers weren’t always profitable, or even often so. Readers failed to pay subscriptions; some journals died after only a few issues. One early financial lifeline was text-based ads, which read like Craigslist for a slaveholding public: “I wish to buy a few negroes, of both sexes, and will pay fair prices in cash,” one typical ad read. Citizens purchased ads to talk, in Twitteresque fashion, to the world. In 1751, William Beasley took out a Virginia Gazette classified to complain about his cheating wife—“I am really of [the] opinion she has lost her senses”—and warn people not to consort with her. — Clive Thompson/Smithsonian Magazine

Like European history, the predecessors of newspapers as we know them today can be traced through Indian history. A fascinating example is that during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, various administrative departments would send reports to the emperor and the council of ministers. Courts employed writ writers who would write edicts and proclamations issued by rulers. These would also be spread orally through official messengers. The Mughals had news writers tasked with sending reports from various regions of the empire to the headquarters.

Portuguese missionaries brought the first printing press to Goa in 1566. The British East India Company installed printing presses in Bombay in 1674, Madras in 1772, and Calcutta in 1779. William Bolts attempted to start the first newspaper in Calcutta in 1776, but concerned officials ordered him to stop and leave for Europe. The Bengal Gazette, or “Hicky’s Gazette,” became the first newspaper in India. Hickey earned the wrath of the British, and he went broke eventually.

After the Bengal Gazette, the Indian Gazette, the Calcutta Gazette, the Bengal Journal, and the Oriental Magazine or Calcutta Amusements launched, Unlike Hickey, these papers operated under the patronage of the British government. Most papers during this period were started by disgruntled British employees. The papers weren’t influential because the circulation was limited to a few hundred copies.

In 1791, the United States ratified the Bill of Rights, which included the First Amendment guaranteeing freedom of speech and press. This informed the debates about freedom of the press around the world for decades to come.

So far, I have tried to highlight the key events in the evolution of newspapers in Europe, the United States, and India. If you’ll bear with me, I want to take a detour and continue with the development of newspapers in the United States. This is not because I secretly long for an H-1B visa but because the United States is the world’s biggest media ecosystem. The industry trends in the United States are also far more advanced than in any other country.

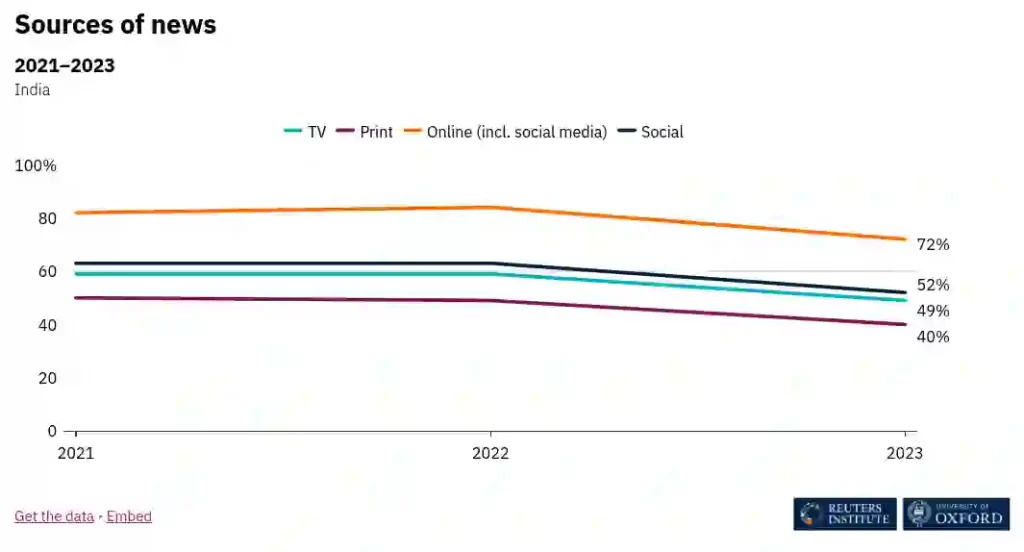

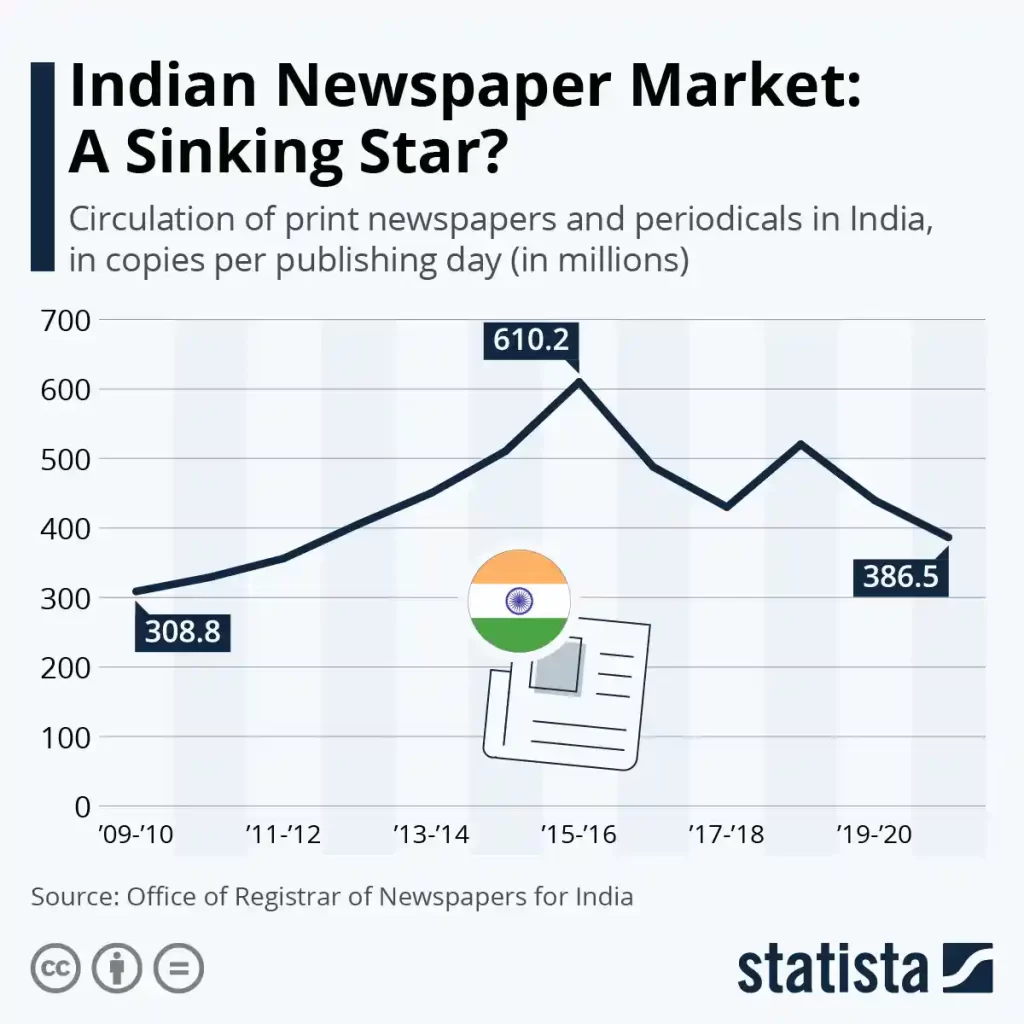

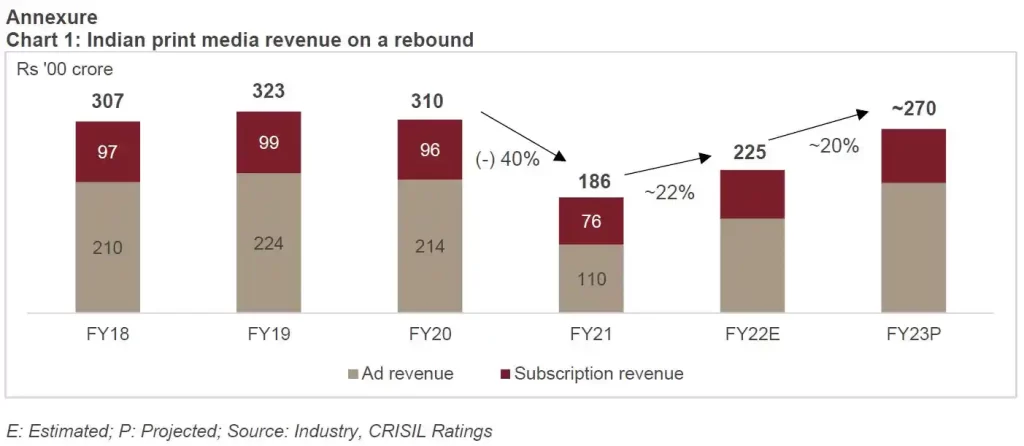

There’s always a temptation to superimpose trends from the West on complex markets like India, but I will resist that. Having said that, looking at what’s happening to American publishers is informative. Indian media and U.S. media might not be mirror images. Still, many broader challenges and trends, like the decline of print, the growth of digital, and the preference for online and social news sources among young people, are the same.

Media observers often hold out the scenario of an ‘Americanisation’ or convergence upon a United States-like media system (Davis 2002; Hallin and Mancini 2004). Little in the evidence reviewed here suggests that this is a likely outcome of current developments. In fact, many American commercial legacy news organisations seem to be facing a more serious crisis than their counterparts elsewhere, and it is by no means certain that this is simply a precursor for things to come around the world. The United States may well be more of an exception and less of a forerunner than is sometimes assumed in discussions of international media developments.

The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Democracy

The American press from the late 1700s until well into the 19th century is indistinguishable from today’s press. Newspapers of that era often exchanged their papers with each other and reprinted select content from other papers with or without attribution. In a way, this was the early version of blogging.

The United States declared its independence in 1775 but was still discovering its feet as a young nation. America didn’t yet have today’s two-party system. George Washington was unanimously elected president for two terms. In fact, the founding fathers were all against the idea of multiple political parties and warned against partisan divisions.

The American press of that era flourished not only because of the government’s steadfast belief in a free press but also because of the profound and virulent differences between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, two of the most influential leaders. Both had irreconcilable views of what the young republic should aspire to. Abusing one another in person was ungentlemanly, so these differences played out in the press directly and through proxies.

Notions of objectivity and fairness weren’t even part of the lexicon. The American press of the era was bitterly partisan and divisive. They openly identified with political parties. Newspapers and political parties were tied at the hip.

Newspaper printing on its own wasn’t enough to make money. Political parties funded loyal newspapers and bailed them out when they were in trouble. Printers were rewarded with lucrative government printing contracts, jobs, and political appointments for their support. In many ways, the party press of the era flourished in large part due to the bitter rivalry between Hamiltonian Federalists and the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans. Leaders from both parties used papers loyal to them overtly and covertly to attack each other.

The government also helped fledgling newspapers by subsidizing postal charges. Newspapers sent to regular readers received a 90% postal subsidy, while postage was free if the papers were sent to other editors and newspapers. This enabled the exchange system I mentioned earlier and helped spread the news across the country.

This early phase of the development of America gave a preview of the treacherous complications of guaranteeing free speech. Facing the prospects of a war with France in 1798, Federalist President John Adam signed the Alien and Sedition Acts into law, making it illegal to say or print anything against the government. Newspaper editors supporting the democratic republicans opposed the bill and willingly provoked the government to get arrested so that they could draw attention to the government’s abuses. The editors channeled this attention and outrage to their benefit, and in the election of 1800, John Adams was defeated, and Thomas Jefferson was elected president.

The naked partisanship wasn’t the only difference between newspapers in the 1800s and today. The early newspapers were colorful and didn’t subscribe to the notion of civility. The election of the 1800s was one of the dirtiest election campaigns in the history of the United States. The political distrust and animosity played out in the press, leading to some memorable insults. Our politics today could use a bit of the color of the 1800s.

Things got ugly fast. Jefferson’s camp accused President Adams of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

In return, Adams’ men called Vice President Jefferson “a mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.”

CNN

As the slurs piled on, Adams was labeled a fool, a hypocrite, a criminal, and a tyrant, while Jefferson was branded a weakling, an atheist, a libertine, and a coward.

John Adams and his people for their part were already spreading rumors that Thomas Jefferson was sleeping with slaves in Monticello (which in fact he was). They also used one of my favorite all-time slurs in American election campaigns by simply saying, ‘Well, you can’t vote for Thomas Jefferson because he’s dead. And how can you vote for a dead man?’”

CBS

While they didn’t get as much attention, magazines and periodicals were also developing, along with newspapers. Johann Rist, a German theologian and poet, is credited with publishing the first magazine Erbauliche Monaths-Unterredungen, or Edifying Monthly Discussions. By the 18th century, like newspapers, magazines were growing in popularity.

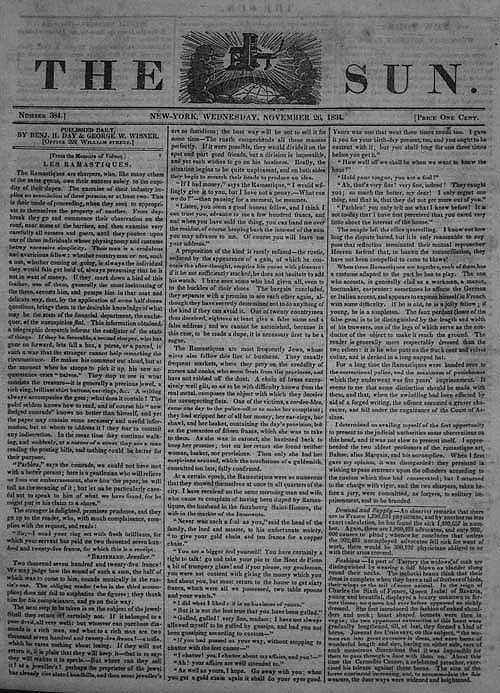

Until the 1830s, newspapers cost about six cents, and the poor and the working class were priced out. All that changed in 1833 when Benjamin Day launched The Sun, a tabloid-style paper priced at one cent. Falling paper costs and the new steam printing press technology made it possible to produce more papers at a lower cost. The Sun was supported by advertising. Unlike the six-cent papers supported by political parties that catered to the “elite,” The Sun focused on general interest stories, crime, gossip, and scandals that entertained the masses. These penny papers introduced newspapers to the masses. Soon, other penny papers started with varying degrees of success.

Some historians describe the penny press as a revolutionary step in the evolution of newspapers, but the reality is much more prosaic. Media scholar John Nerone argues that penny papers were a step in the natural evolution of newspapers, and there wasn’t anything revolutionary about them. Since penny papers were supported by advertising, they claimed to be independent. In reality, American newspapers remained partisan well into the 19th century.

The spread of fake news on the internet has become a major concern today, but it’s nothing new. Early American newspapers had a tenuous relationship with the truth. Newspaper publishers weren’t above making shit up to sell papers. One of the most famous made-up stories to have ever been published is the six-part series in The New York Sun on the presence of life on the moon. The series depicted a fantasy lunar world full of forests, oceans, unicorns, bipedal beavers, and conversational man-bats. The story spread like wildfire across the United States and Europe.

In Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, there’s a scene where Tom Hollander, who plays Cutler Beckett, tries to coerce William Turner to find Jack Sparrow and recover the compass from him. Beckett says:

Will Turner: Somehow I doubt Jack will consider employment the same as being free. Lord Cutler Beckett: Freedom! Jack Sparrow is a dying breed. The world is shrinking. The blank edges of the map filled in. Jack must find his place in the new world or perish.

“What hath God wrought!”

That was the first telegraph message sent by Samuel Morse. With that message, the world became a smaller place. This reminds me of another scene from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End:

Barbossa: The world used to be a bigger place. Jack Sparrow : World’s still the same. There’s just less in it.

The first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858 but failed within weeks. By 1861, the transcontinental telegraph line had been completed, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. In 1861, a third cable was successfully laid after another failed attempt between Ireland and Canada. With that, transatlantic communication became possible.

The world was never the same again.

The impact of the telegraph on newspapers was dramatic. The telegraph helped newspapers transcend physical limitations and transformed the business of news. Journalist Tom Standage called the telegraph the Victorian internet in his book of the same title. Thanks to the telegraph, newspapers no longer had to publish stale news. They could gather breaking news from across the world. Several large newspapers began publishing multiple editions in a day by updating the same paper with the latest news.

Today, we lament that news has become entertainment, but this bellyaching is due to a lack of historical memory. The impulse to sensationalize news has been a constant throughout the history of news. In the aftermath of the telegraph, newspapers maintained public bulletins outside their offices that would be updated day and night with telegraphic updates. Some papers used to project cartoons between election updates, and some even hired artists to enact news events.

Collecting news and using a telegraph to transmit it was costly. In 1846, five New York City newspapers agreed to share expenses to gather news, and the Associated Press (AP) was created. The AP used everything from pigeons and ponies to row boats to intercept European ships to collect international news and transmit it over the telegraph. Over its 177-year history, the AP has been a witness to the first draft of history. In 1850, Paul Julius Reuter used pigeons to deliver stock prices between Brussels and Aachen due to a gap in telegraph lines. In 1851, he moved to London and started Reuters, the other famous wire service. In a short span, wire services became important suppliers of news for newspapers.

A confluence of factors led to the dramatic growth of newspapers from the 1850s. As the century progressed, railroads spread across the United States. This opened up new economic opportunities, enabling enterprising settlers to tame the vast wild lands. The completion of the transatlantic cable in 1861 made long-distance communication easy. As territories spread, factories and transportation systems expanded. Another important enabler for the proliferation of newspapers was the US postal system. Postal coverage spread throughout the 1880s, and newspapers enjoyed preferential rates.

During the same period, literacy rates in the United States rose as the number of schools and colleges increased. Advances in printing technology reduced the cost of printing and increased the output. Since the invention of the Gutenberg press, the printing press had remained unchanged. The wooden presses required considerable force and were prone to breaking. This changed in the 1800s.

Early 1800: Charles Mahon (Earl of Stanhope) is credited with building the first iron printing press. This increased the output to 200–400 pulls per hour.

1810: Frederick Koenig and Andreas Bauer patented a steam-powered cylindrical printing press. In 1814, The Times in London printed the first newspaper with this design, capable of printing 1100 sheets per hour.

1846: Richard Hoe creates the revolving press that can print up to 8,000 sheets an hour. The output improves to 20,000 sheets with further enhancements.

1863: William Bullock improves on Richard Hoe’s rotary press to create a press that can print 12,000 sheets on both sides. Later improvements raised this number to 30,000.

1886: Ottmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype automatic typesetting machine that revolutionized printing. It removes the need for manual typesetting, thereby speeding up printing.

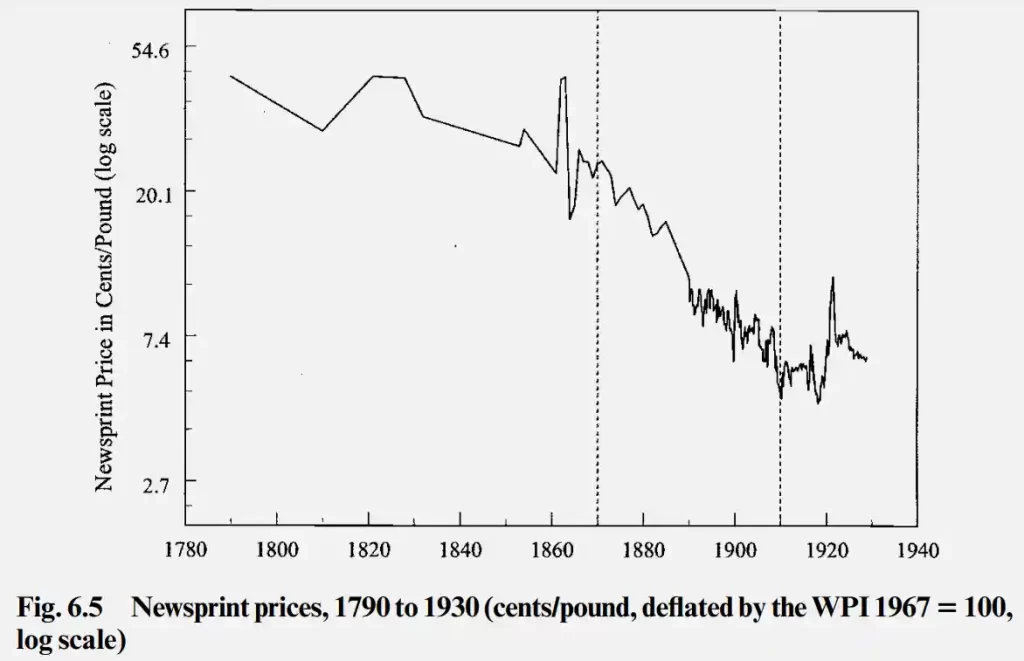

Despite all these advancements, newspapers weren’t cheap. They cost 4-6 cents at a time when the average wage of a worker was one dollar. Newspapers remained an elite affair. The major obstacle stopping newspapers from reaching the masses was the cost of printing.

Until the 1870s and 1980s, paper was made from used clothes and rags. As printing technologies improved, the demand for paper increased, but rags were in short supply. In the 1850s, many countries banned rag exports, which sent prices shooting up. But in the late 1860s, inventors figured out a way to make paper from wood pulp, and the price of paper fell. This kick-started the era of mass newspapers catering to the long-neglected working class.

As print technologies improved, communication technologies improved as well.

“Mr. Watson – Come here – I want to see you.”

Those were the words on the first telephone call on March 10, 1876, between Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Thomas Watson.

Twenty years ago, America invaded Iraq based on the lies that Saddam Hussein was developing mass destruction (WMDs) and had links to al-Qaeda. All the major news outlets became cheerleaders for the Bush administration and helped sell the war to the American public. Over half a million people died, and the war cost the United States over $3 trillion. This wasn’t the first time the American media was complicit in warmongering.

In 1895, the Cuban War of Independence broke out. This was when the rivalry between Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal hit a fever pitch. The press barons were battling each other for supremacy, and their papers featured lurid and sensationalist stories to increase circulation. Both saw the Cuban War as an opportunity to achieve dominance.

Throughout the 1890s, both papers published exaggerated and even downright false stories. They were agitating for war, pushing the United States to intervene in Cuba. The term “yellow journalism” was coined to describe the sensationalist style of news. In 1898, the US invaded Cuba, defeated the Spanish, and liberated Cuba. Some historians attribute the invasion to warmongering by the press, but others argue that while the press played a role in the decision to invade by swaying sentiment, they weren’t the cause.

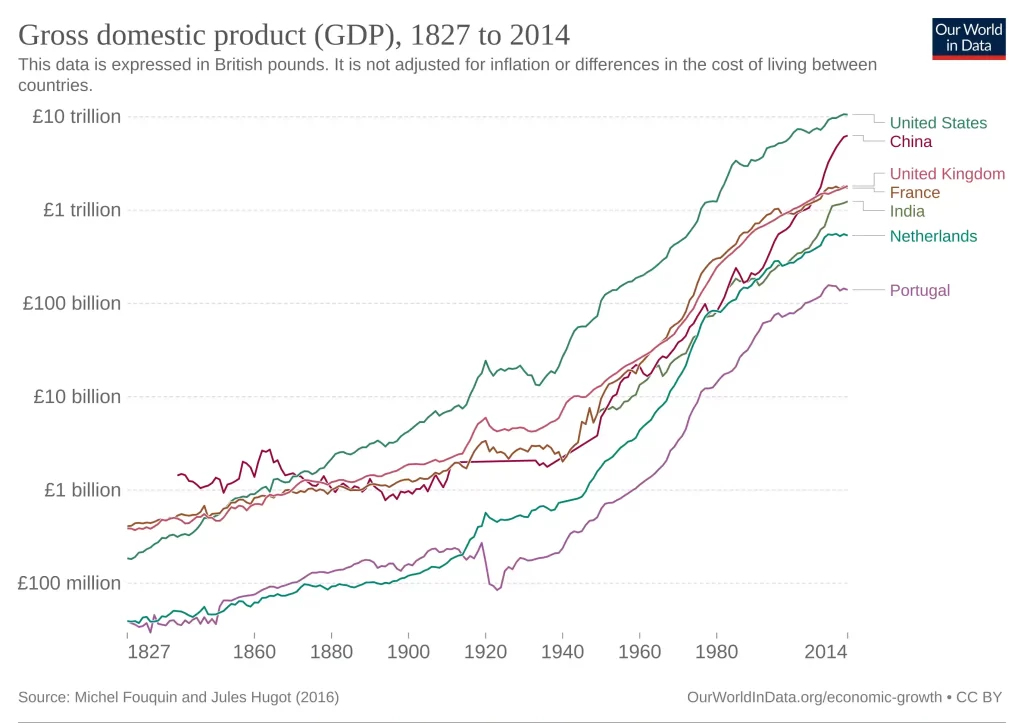

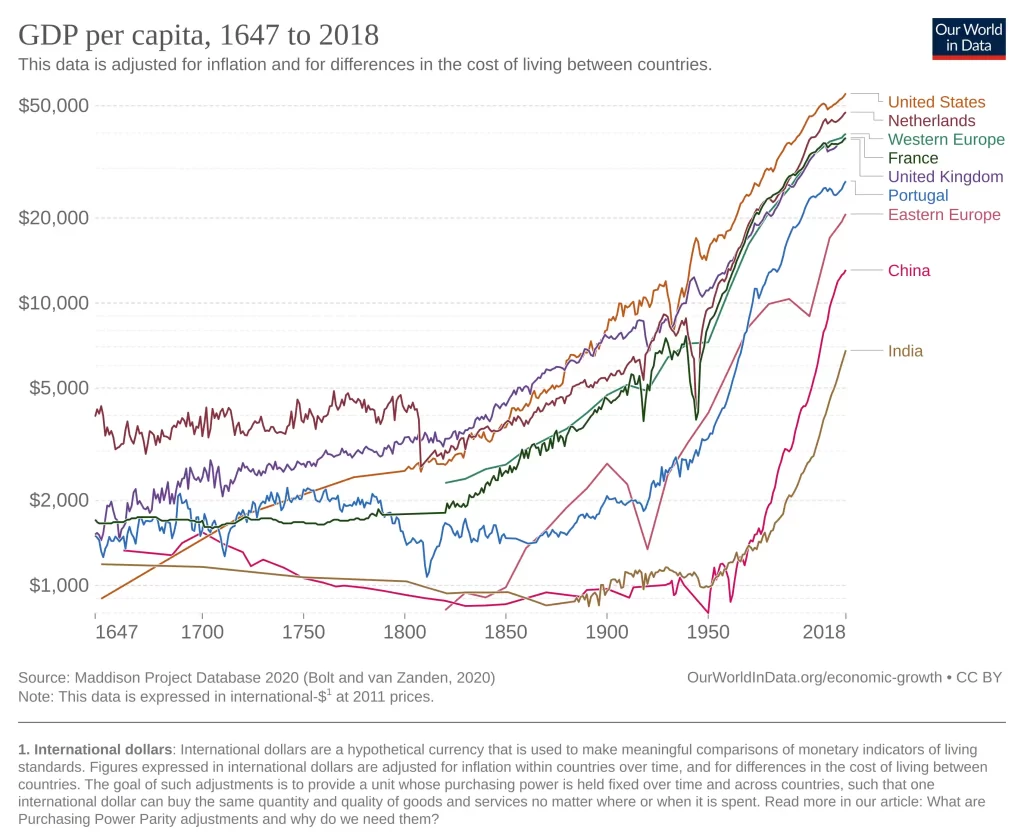

At the turn of the 19th century, the United States was entering the second industrial revolution. The economy was booming thanks to expanding transportation, expansion of cities, immigration, new communication technologies, and advancements in manufacturing technologies.

A key development that unleashed the ravenous spirit of capitalism was the development of the concept of limited liability in the mid-1800s. Before this period, there was no concept of limited liability, and all shareholders were personally liable. Limited liability enabled a new breed of corporations to raise money from the public. This, along with the other factors, supercharged the transition of the United States from an agricultural to a manufacturing economy. Individual and family-owned businesses gave way to large corporate entities.

As the American economy was taking off, so was mass consumerism and the demand for advertising. In 1841, Volney Palmer started a real estate agency in Philadelphia, looking to make a living. Business was dull because the city was in the throes of a depression. Palmer soon started a coal agency, an unlikely addition to the real estate business, but times were tough.

In 1842, he started a newspaper advertising business after spotting an opportunity when he saw underutilized ships and canals. He entered into contracts with newspapers to sell their advertising space, becoming, in essence, a newspaper advertising agent. He drummed up business by convincing manufacturers to sell their wares in other places by taking advantage of the empty ships and canals. While there were many failed attempts, many historians recognize Volney Palmer’s operation as the first advertising agency.

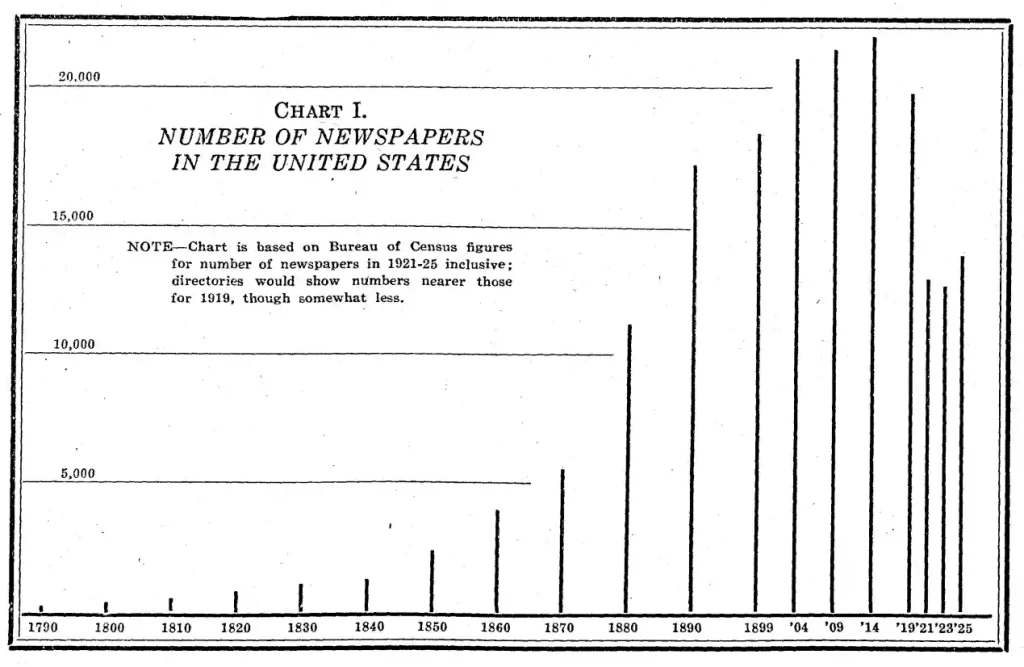

The number of newspapers grew exponentially from a few hundred in the 1700s to more than six thousand by the 1870s. Thanks to the growing economy. There was tremendous demand for advertising. Display advertising demand rose as railroads enabled companies to reach consumers across the United States. America imported the department store format from Europe, and retail advertising demand exploded. Advertising as a proportion of newspaper and magazine revenue rose from 44% in 1879 to 54.5% in 1909, reaching 60% by 1909.

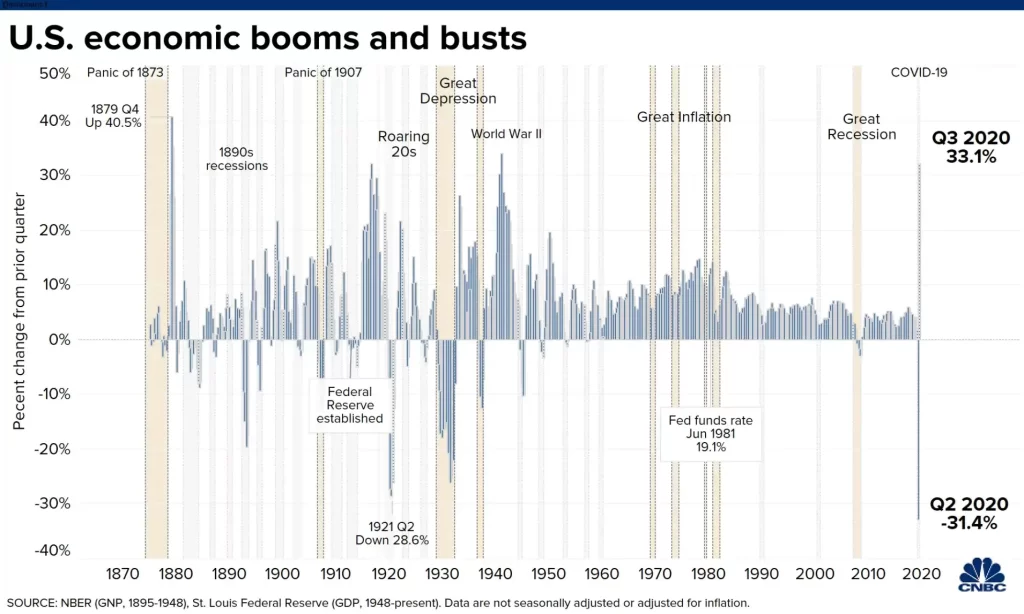

From the 1850s, the United experienced dramatic and volatile economic growth. The shaded areas represent recessions.

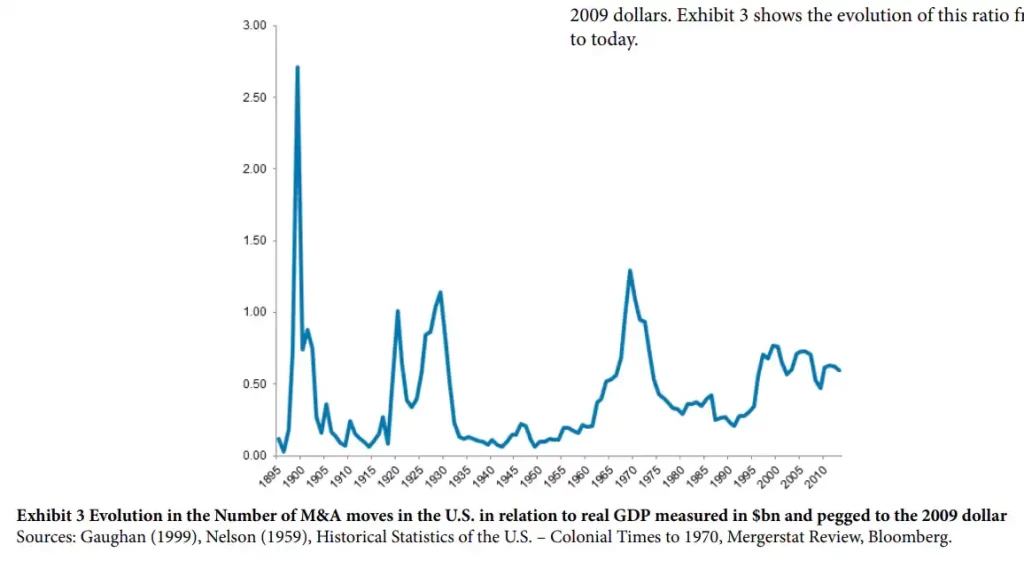

Technological advancements led to a shift from small businesses to large companies. The boom and bust cycles of the period led to rapid production, overcapacity, and ruinous competition. The excessive competition led to a sharp drop in prices and profitability and precipitated consolidation among large swathes of the industry. The United States saw the largest merger wave in history from 1895. About half of the manufacturing industry may have participated in the mergers.

People like John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Andrew Carnegie emerged as the greatest tycoons America had ever seen. They used brutal tactics such as collusion, cartelization, political capture, and stock price manipulation to crush competition. They had near monopolies on oil, railroads, and steel at their peak. Major industries like coal, sugar, whiskey, tobacco, and meatpacking used trusts to integrate vertically and horizontally. These trusts had near total control over the industries they operated in. John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil was the poster child of this era. It controlled 90% of American oil refineries.

Ida Tarbell saw Rockefeller’s brutal tactics when he destroyed her father’s fledgling oil business at 14. Despite studying biology, she discovered her love for writing and became a journalist. Working at McClure’s magazine, she started to publish a mammoth expose of Standard Oil, beginning in 1902. Over 19 parts, she laid bare the machinations of the oil refining giant and its brutal practices. Her dogged work was responsible for the eventual breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. The Standard Oil series is still considered one of the finest examples of investigative journalism.

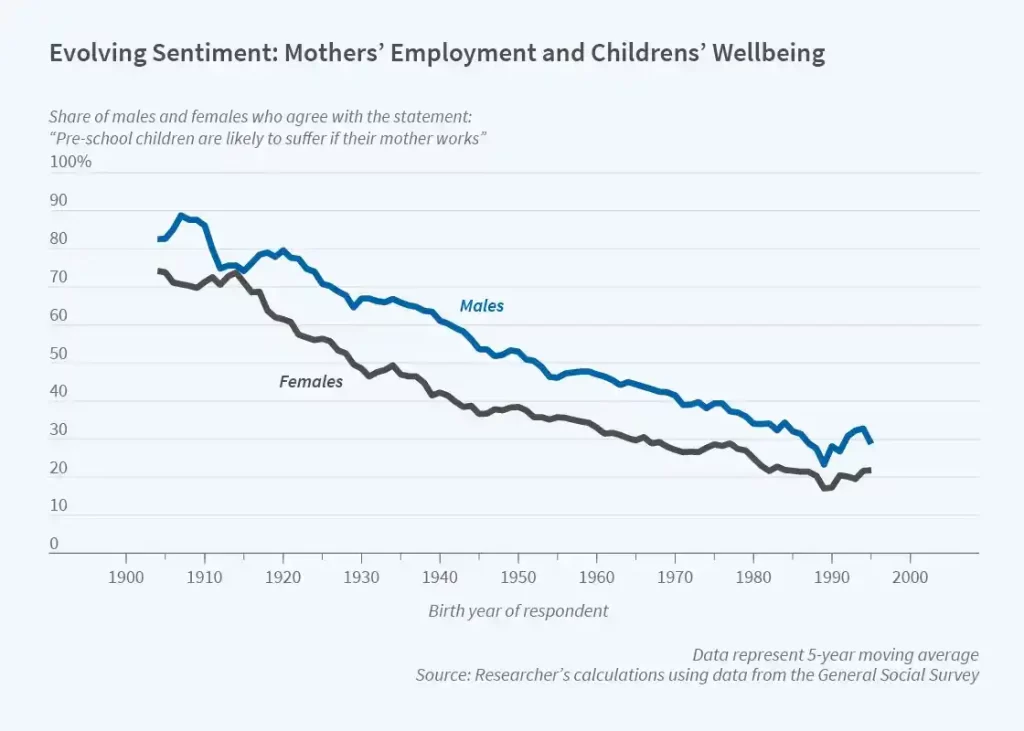

In reading the history, it wasn’t surprising to me that the role of women in newspapers was ignored. Even as America grew, attitudes about women remained rooted in the dark ages—a woman’s place was at home.

Despite the conservative views, several trailblazing women worked as investigative reporters, writing about important issues under pseudonyms:

The young woman was one of the nation’s so-called girl stunt reporters, female newspaper writers in the 1880s and ’90s who went undercover and into danger to reveal institutional urban ills: stifling factories, child labor, unscrupulous doctors, all kinds of scams and cheats. In first-person stories that stretched over weeks, like serialized novels, the heroines offered a vision of womanhood that hadn’t appeared in newspapers before—brave and charming, fiercely independent, professional and ambitious, yet unabashedly female.

Throughout the history of the United States, you can see the tension between the state and the press. While people consider America a beacon of free speech, that wasn’t always the case. In 1917, the United States entered the world war and, within weeks, passed the Espionage Act to stifle dissent. The law was amended in 1918 with the Sedition Act and had a chilling effect on free speech. Over 2,000 people were prosecuted under the law.

As circulation and advertising revenues grew, so did competition. Commercial interests forced newspapers to be less partisan. Rising advertising demand and revenues forced newspapers to appeal to the masses. Newspapers couldn’t afford to alienate their readers with partisan takes. From the late 1900s, the American press began its slow journey toward professionalization.

The share of political newspapers that claimed to be independent rose from 11 percent in 1870 to 62 percent in 1920.3 Another measure of bias is the use of charged language by the press. Negative words such as “slander,” “liar,” and “villainous” are used by papers to dismiss undesirable statements; words such as “honest,” “honorable,” and “irreproachable” are used to defend political heroes. Using textual analysis, we find a substantial drop in partisan and charged language across the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Rise of the Fourth Estate: How Newspapers Became Informative and Why It Mattered

The period from 1880 to 1990 was the golden age for American newspapers. Advancements in printing technologies, communications, and photography made newspapers even better, faster, and more visual. They enjoyed absolute dominance since they were the only mass medium for advertisers. Even during the Depression of the 1930s, newspaper circulation continued to rise.

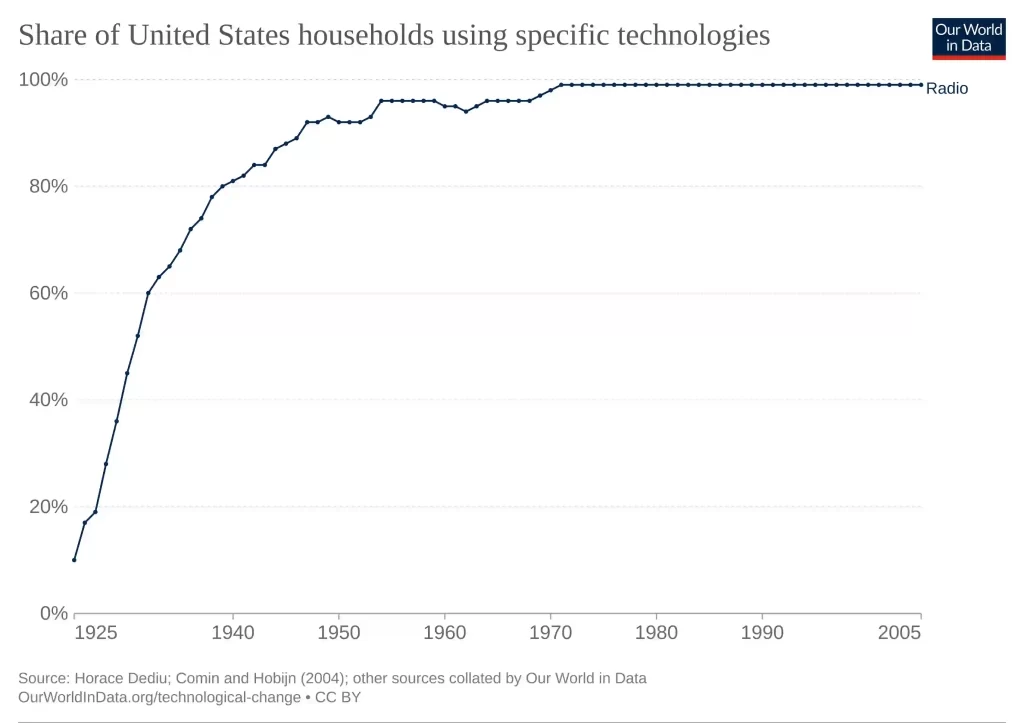

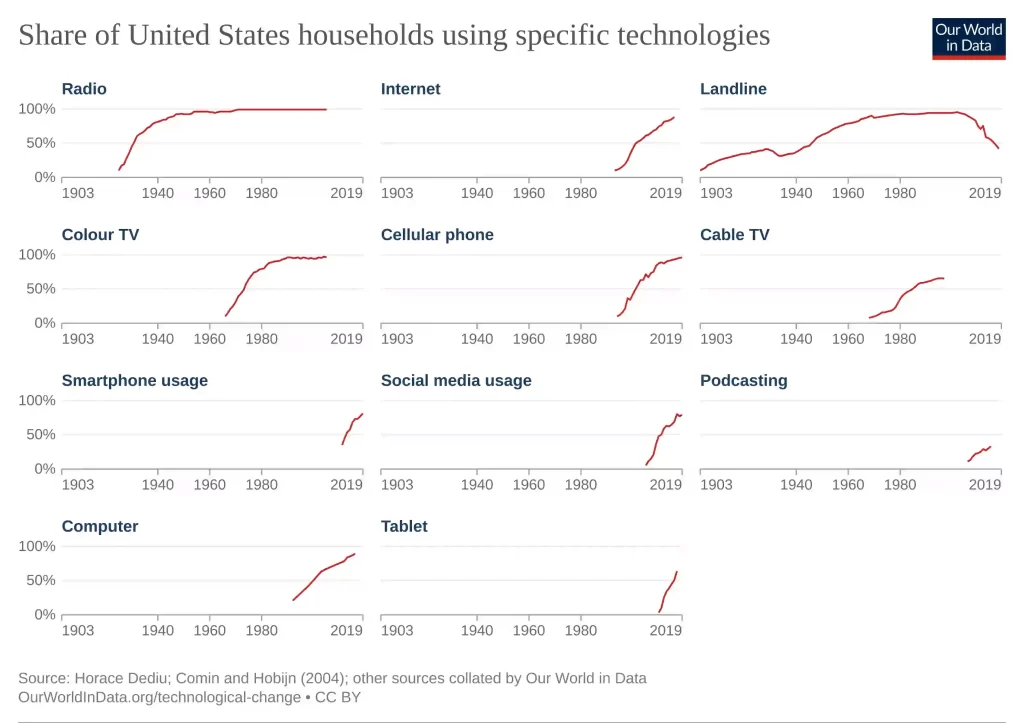

But the roots of their troubles today can also be traced to this period. Like the telegraph, the radio also had many fathers. In 1920, KKDA, owned by Westinghouse Electric, became the first radio station to go on air. By 1930, about 45% of Americans had a radio set, and radio advertising had crossed $100 million. Between 1927 and 1930, radio advertising rose by seven times, and not even the Great Depression could put a dent. World War II further increased the popularity of radio, as people preferred getting the news about the war from radio to newspapers.

Though absolute circulation rose, the great depression of the 1930s was a death knell for many newspapers as advertising revenues fell by 40–45%. Several newspapers shut down; others slashed costs, cut salaries, and merged. The slow decline of newspapers started around this time.

U.S. advertising expenditures as a share of National Income had declined from a peak of more than four per cent in the 1920s to 1.5 per cent in 1945, then recovered in the post WWII era to just under three per cent in 1957, still shy of the pre-Great Depression peak

Aggregate Advertising Expenditure in the U.S. Economy: What’s Up? Is It Real?

Today, the plight of newspapers is so dire that governments are intervening to protect them. But people forget that they were the barbarians of yesteryear. In the early days, radio stations couldn’t gather news, so they read out the stale news from newspapers. They could, however, buy timely news from newswire services like the Associated Press (AP).

Newspapers felt threatened by the prospect of losing sales and advertising revenues. Since the AP was a cooperative owned by the newspapers, it was forced to stop selling news to radio broadcasters. In a failed attempt, newspapers even tried to collude to stop radio broadcasters from broadcasting news.

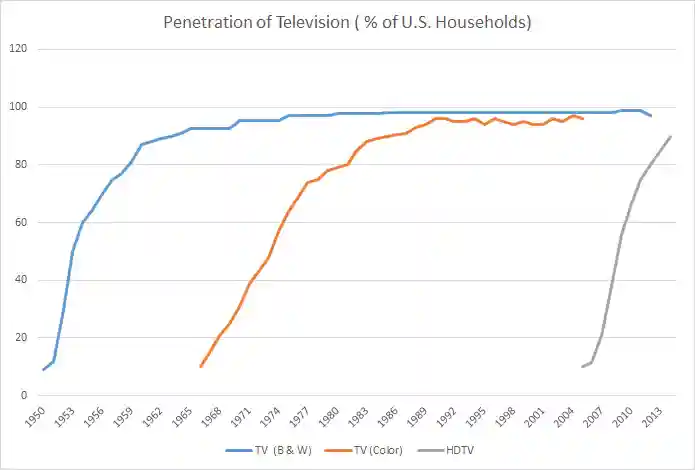

Like the telegraph and the radio, the invention of television was the result of the efforts of many scientists and engineers in the 1800s and 1900s. There were experimental broadcasts starting in the 1920s, but the first regular broadcast began in 1939 by the National Broadcasting Company (NBC).

By 1955, 60–70% of US households had a television. From $128 million in 1951, TV advertising spending hit $1 billion in 1955. Television started to take some advertising away from newspapers. It’s easy to overextend this assumption of TV hurting newspapers, but one has to be careful. It’s important to remember that television advertising and newspaper advertising are imperfect substitutes.

In 1952, 6 percent of all advertising spending, or $454 million, went to television ads; by 1960, $1.6 billion, or 13 percent, did.

FCC

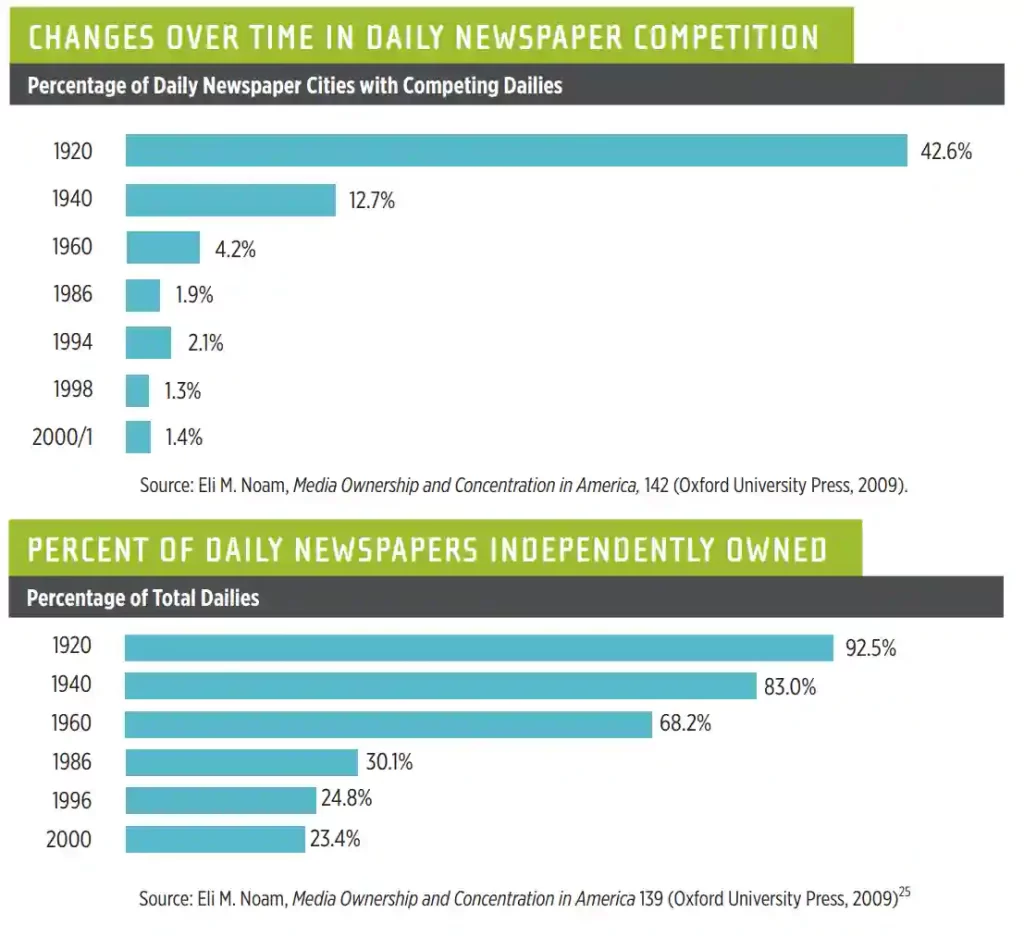

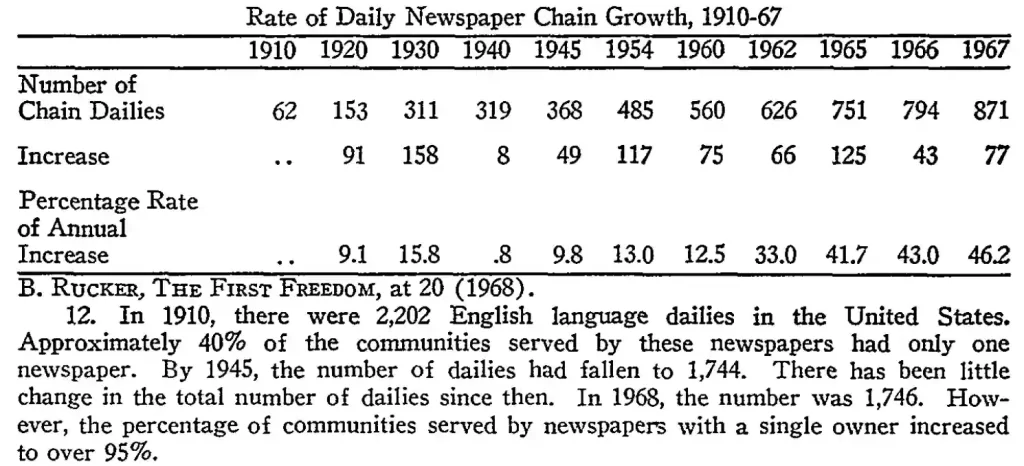

American newspapers started feeling the heat with the rise of radio and television. Newspapers didn’t know it at the time, but their fortunes had turned. The other important trend throughout the 1900s was consolidation. The number of newspapers hit a peak in 1909 and started declining. There was a corresponding rise in the number of newspaper chains. By 1933, newspaper chains controlled 37% of all newspaper circulation.

Unlike the pre-Civil War era, running a newspaper was no longer an amateur operation. Installing printing presses, purchasing real estate, and setting up distribution required massive capital investments. Cutthroat competition for readership in the 1900s further complicated things. Fixed costs continued to rise as printing technologies advanced throughout the 1990s. These upfront costs created entry barriers for new newspapers, and they enjoyed significant pricing power and obscene profit margins due to their reach.

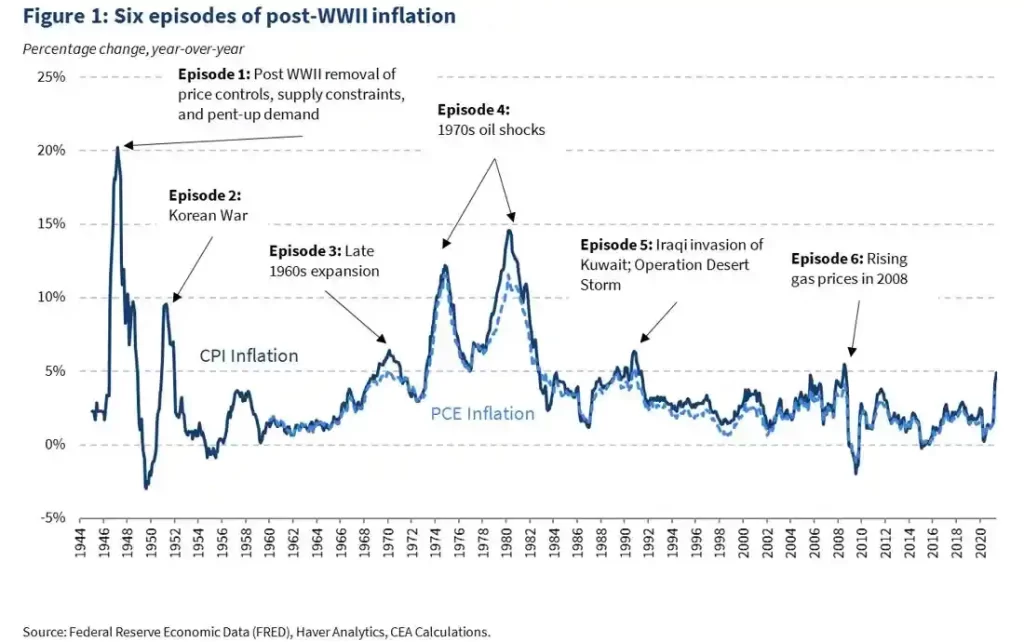

The 1950s were a tipping point for the American newspaper industry. A series of unfortunate coincidences set the stage for massive consolidation. As World War II ended, the United States lifted the wage freezes imposed in 1942. The pent-up demand led to a massive inflationary shock and sent newspaper production costs spiraling. This was a precipitating factor for consolidation.

The soaring newspaper profits caught the attention of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS changed the appraisal methodology of newspaper companies from book value to market value around this time. This change made it impossible for many independent newspaper owners and their heirs to pay the new taxes. They were forced to sell, and this led to the further consolidation of newspapers.

Even as newspapers consolidated, the quality of journalism remained high. Papers continued to invest in editorial.

Daniel Ellsberg, an analyst at the RAND Institute, leaked a classified study about US involvement in Vietnam to reporters at The New York Times and The Washington Post in 1971. The study showed that successive administrations had deceived the American public about the purpose and true cost of the war. The war was an epic disaster. This led to the Watergate scandal, which ended with the resignation of President Richard Nixon. In a high-watermark for American journalism, Arthur Sulzberger, chairman of The New York Times, and Katherine Graham, owner of The Washington Post, bet the entire house in a remarkable display of courage and published the leaked documents. The Nixon administration tried to stop the publication, but the US Supreme Court allowed the papers to publish in a landmark decision, affirming the freedom of the press. This period marked the birth of the adversarial American press.

The scale of the consolidation was stunning from the 1960s. In 1920, 92% of American newspapers were independently owned, and 42% of American cities had competing newspapers. By 1986, only 30% of the newspapers were independently owned, and only 2% of the cities had a competing newspaper. By 1970, 98% of US newspapers were monopolies, and the vast majority of cities had no competing papers.

Large chains like Gannett, Knight Ridder, and McClatchy gobbled up these newspapers.

Between 1960 and 1980, 57 newspaper owners sold their properties to Gannett Co. By 1977, 170 newspaper groups owned two-thirds of the country’s 1,700 daily papers. From 1969 to 1973, 10 newspaper companies went public, including the Washington Post Co., New York Times Co., and Times Mirror Co.

The U.S. Newspaper Industry in Transition

At the beginning of the twentieth century, eight groups controlled just 27 journals. Led by Hearst and Edward Scripps that number climbed to 63 groups owning 328 papers by 1935. In the final decade of the century, 135 chains controlled 1,228 journals.

Ambarish Chandra and Ulrich Kaiser

Wall Street took note of the ludicrous profit margins and wanted a piece of the action.

Exactly how profitable are newspapers? At least as measured by operating margins, the answer is very profitable. (Operating margin is profit divided by revenue, before taxes. It is a way to define a company’s efficiency.) Using this measure, newspapers achieve profit margins about two to three times the average for U.S. manufacturing industries. (This is the category that newspapers are placed in by the Census Bureau.)

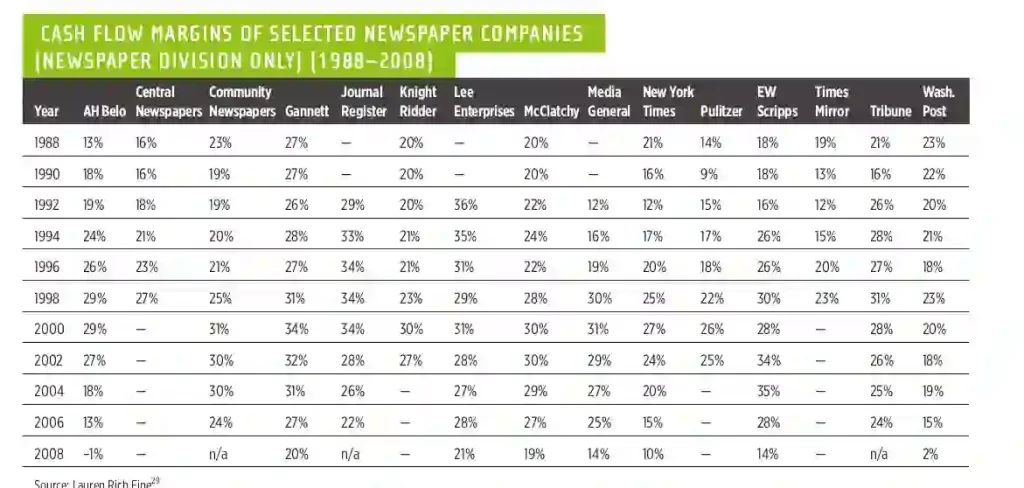

The average operating margin for a U.S. manufacturing company in 1997 was 7.6 percent. The comparable average for publicly traded newspaper companies in 1997, according to Veronis, Suhler & Associates, Inc., was 19.5 percent. Gannett, often cited as an industry benchmark for profitability, achieved 26.6 percent in 1997. Some newspaper companies, such as The Buffalo News, owned by investor Warren Buffett, had margins that were in the 30’s. With the exception of television stations, which often enjoy operating margins of more than 45 percent, newspapers are hard to match for profitability among U.S. media investments. In the mid-1990’s, newspapers outperformed consumer magazine and book publishers, direct mail and promotional services, radio broadcasters, cable and pay-per-view networks.

Lou Ureneck, Nieman Lab

The acquired papers were no longer owned by family owners with ties to their communities. They were Lego blocks in large listed corporations run by managers seeking efficiencies. Since they were listed on the stock exchanges, shareholders demanded continued profits. The American newspaper industry took a sharp left turn. Profits took center stage, and the quality of news became a distant priority. This quote by an analyst at Drexel Burnham in 1986 was telling:

John Reidy, who follows the newspaper industry for the securities firm Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., said, “Properties in the right market are very attractive businesses on a long-term basis. . . . There is an increasing recognition that there is no electronic replacement for newspapers, and many see the attraction of doing business as the only newspaper in town.”

The US Congress passed the Newspaper Preservation Act in 1970 to ensure the survival of newspapers. The law provided exemptions to antitrust laws by allowing newspapers to merge their production and commercial capabilities as long as they maintained separate editorial operations. The intuition was that this would maintain a plurality of voices and stop the inexorable rise of one-paper towns. The law essentially allowed papers to collude and fix prices with a legal sanction. It wasn’t enough.

The Act grants participants in JOAs immunity from general antitrust laws and permits them to engage in such otherwise illicit practices as price-fixing, profit-pooling, and market allocation.

Joint Operating Agreements In the Newspaper Industry

It’s an article of faith among some publishers and media observers that the internet is responsible for the newspaper industry’s woes.

That’s a bald-faced lie.

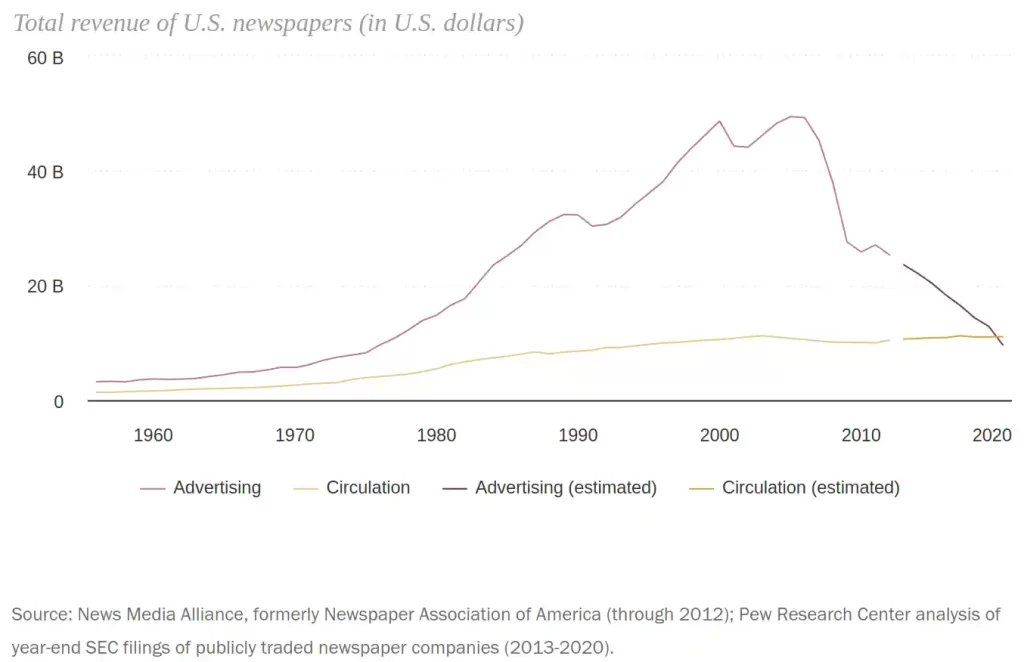

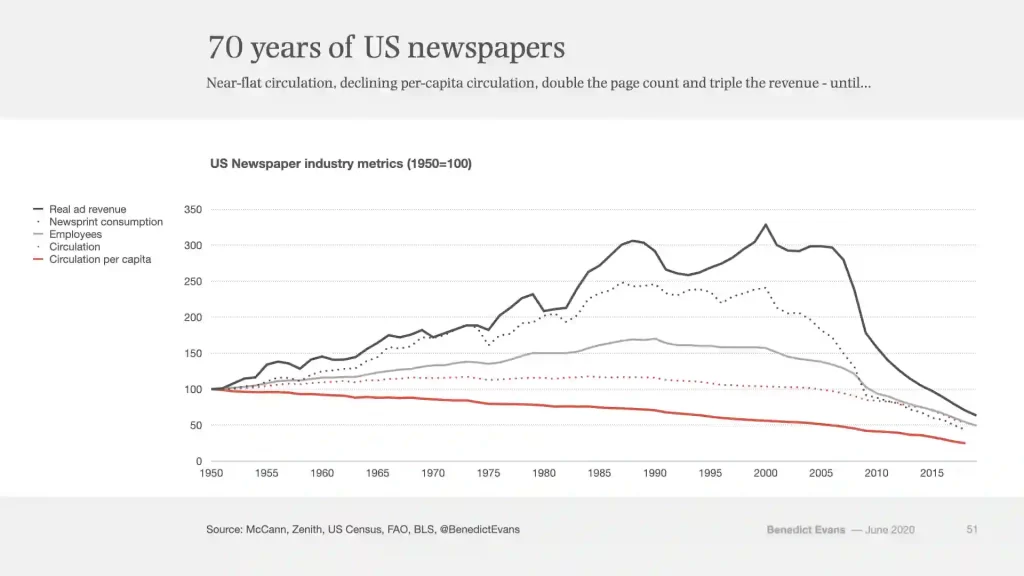

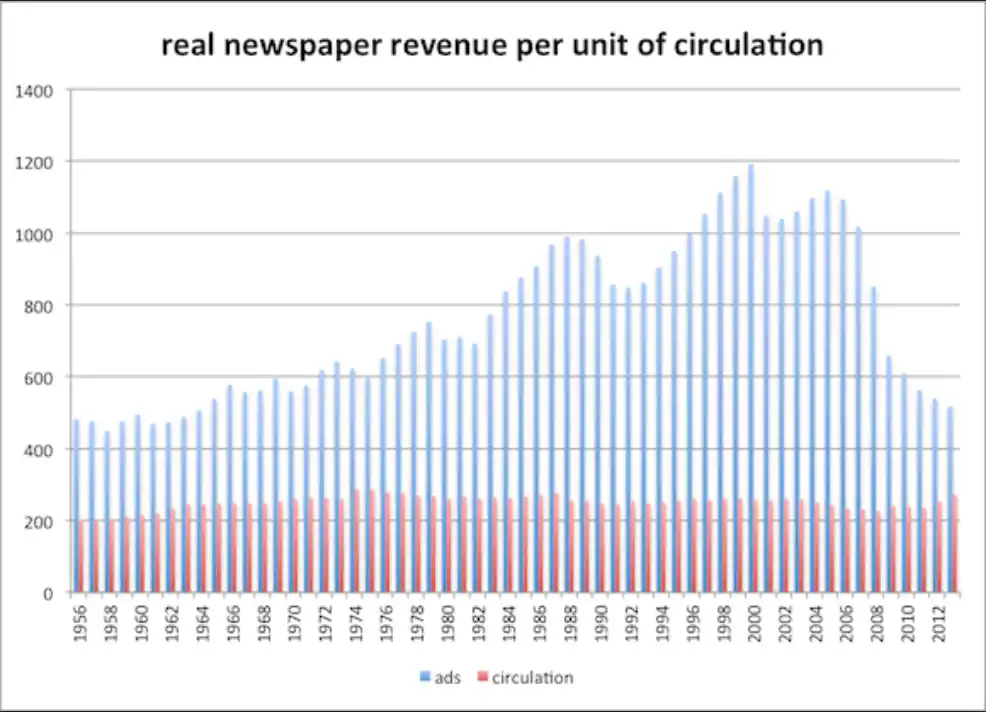

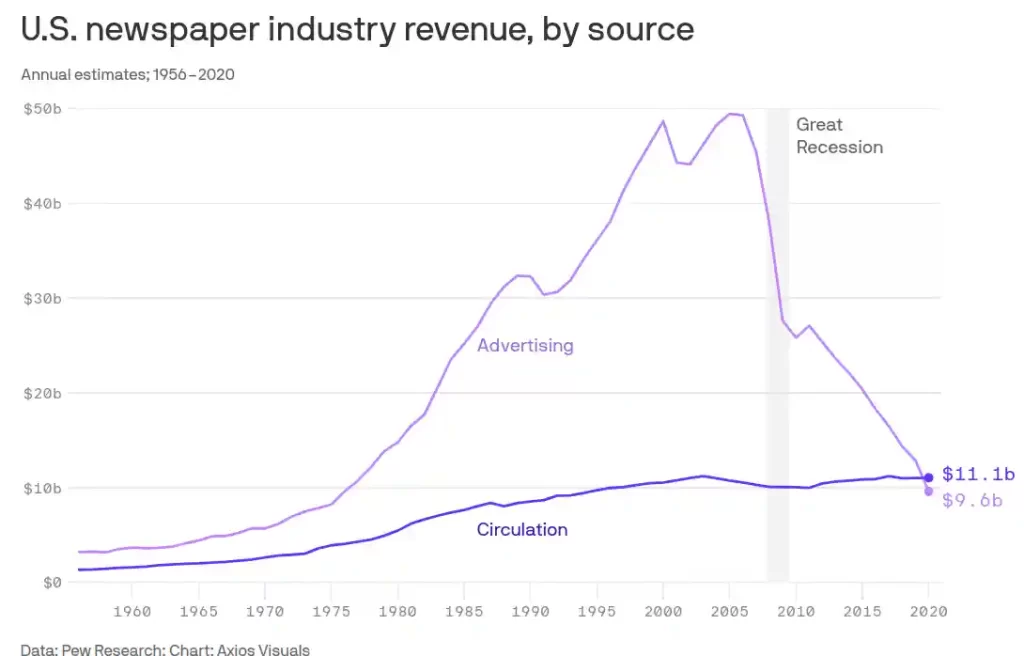

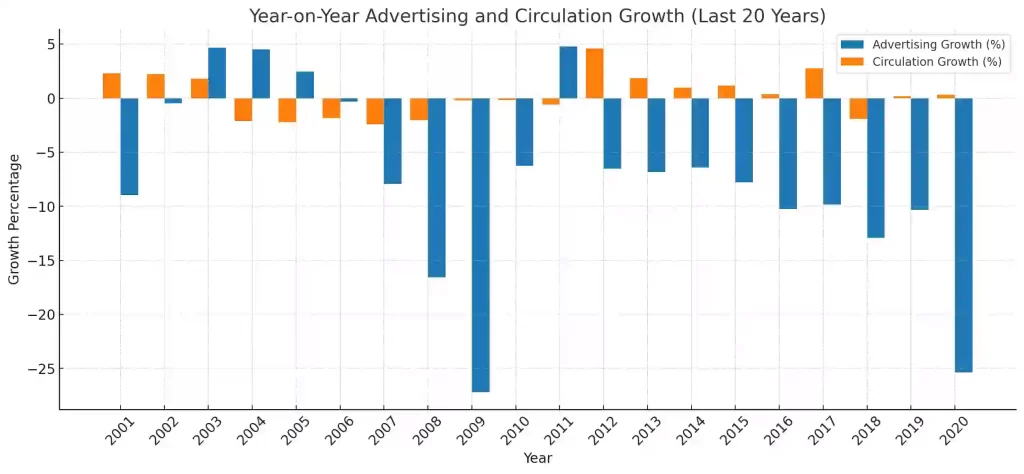

As I mentioned earlier, the newspaper industry’s troubles predate the internet. Discussions about the problems of newspapers are accompanied by charts like this. You’ll hear people say everything was hunky-dory until the 2000s, and then the internet came and destroyed the poor newspapers. But headline numbers obscure a lot of the underlying trends. The popular canards are, well, stupid.

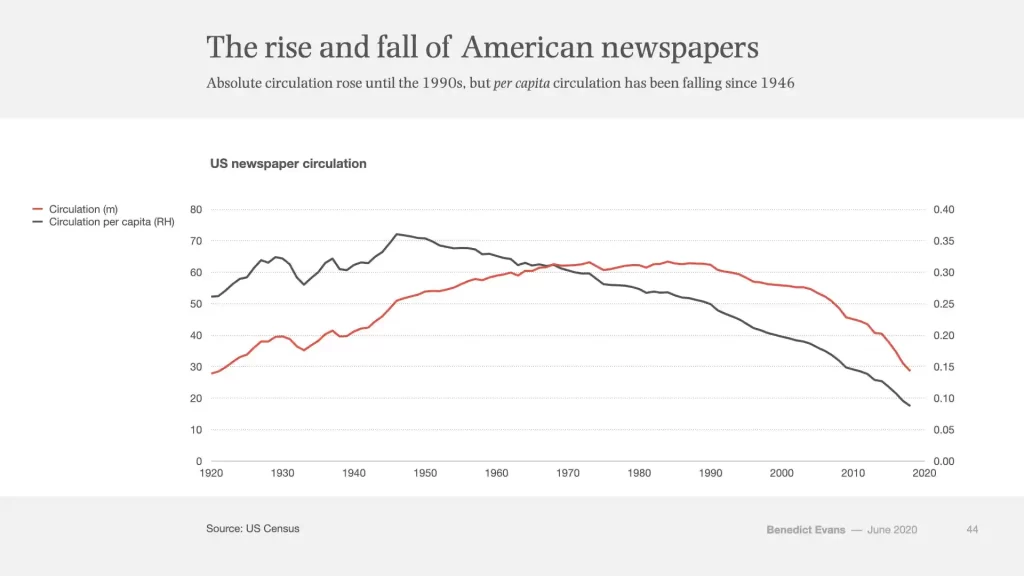

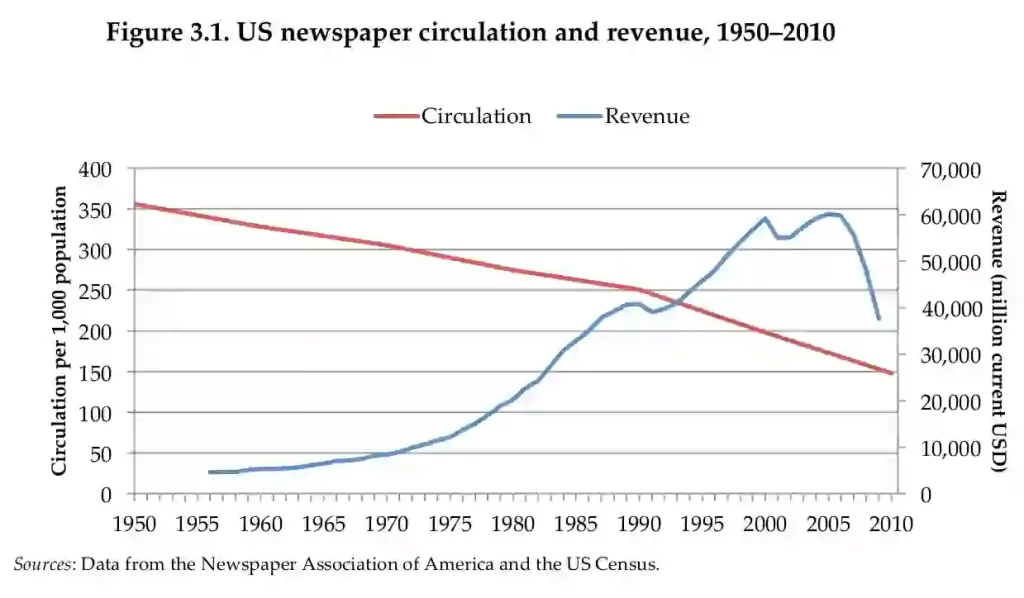

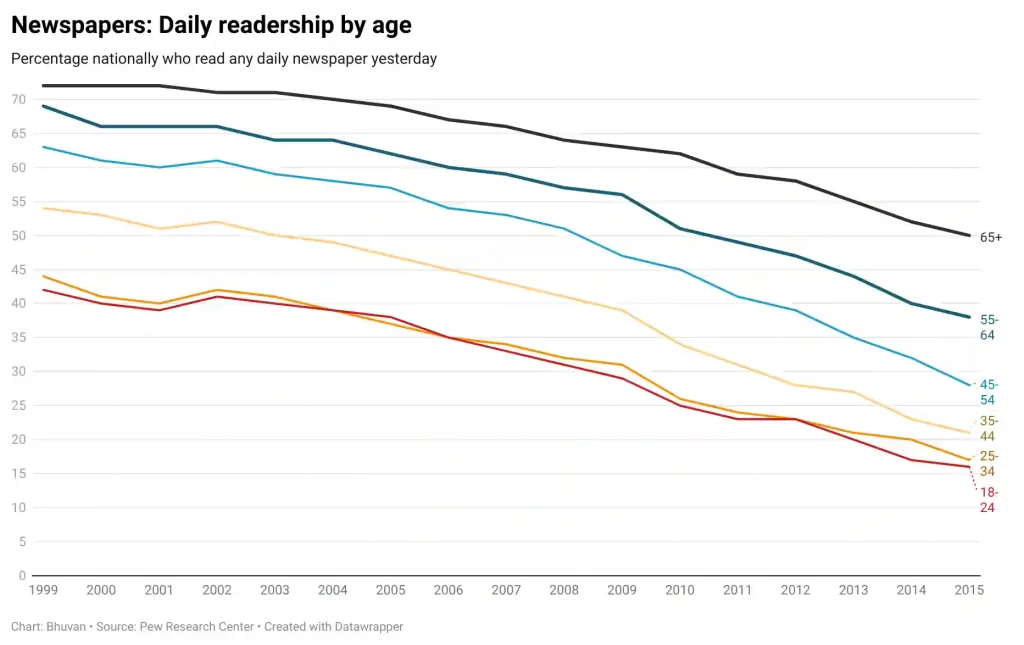

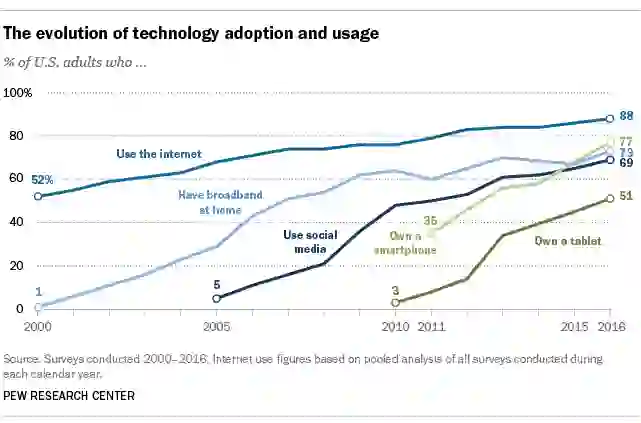

Tech observer and venture capitalist Benedict Evans had done yeoman’s work going back in time to collect numbers of American newspapers. Here’s the real story: newspaper circulation peaked in 1984 at 63.3 million copies and has been falling ever since. But the real story is that newspaper circulation per capita peaked around 1945. In other words, a smaller percentage of the population bought newspapers, even as the population grew.

On one hand, the dominance of newspapers has been diminishing for a long time. From 1940 to 2010, the number of daily newspaper subscriptions in America rose by 2 million—but the number of households increased by 83 million. Here is another way of looking at it: about as many Americans subscribe to newspapers today as did in the early 1940s, even though the number of households is more than three times larger.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

Here’s a chart of advertising revenues, newsprint consumption, employees, total circulation, and per capita circulation indexed to 1950.

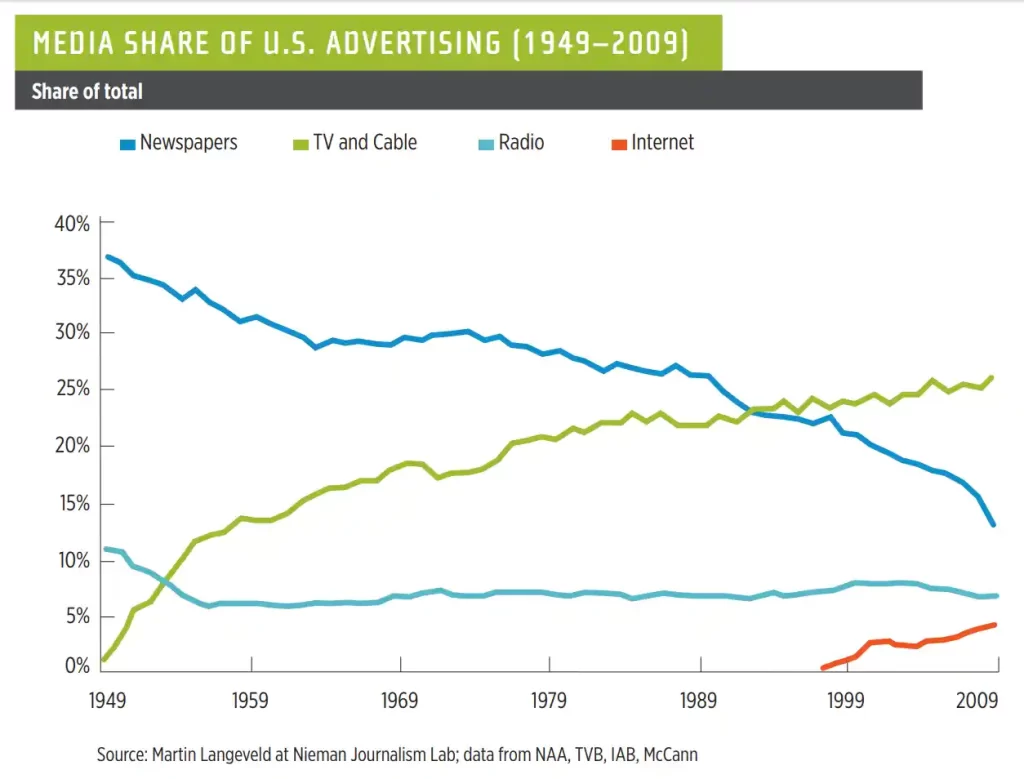

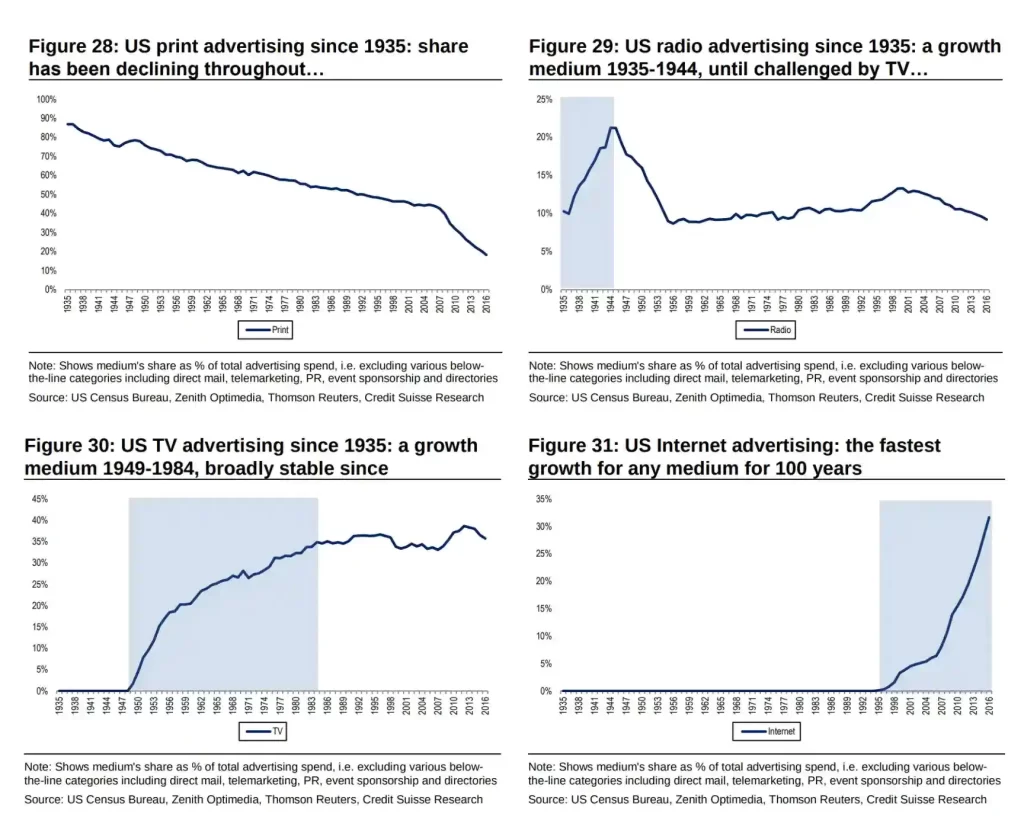

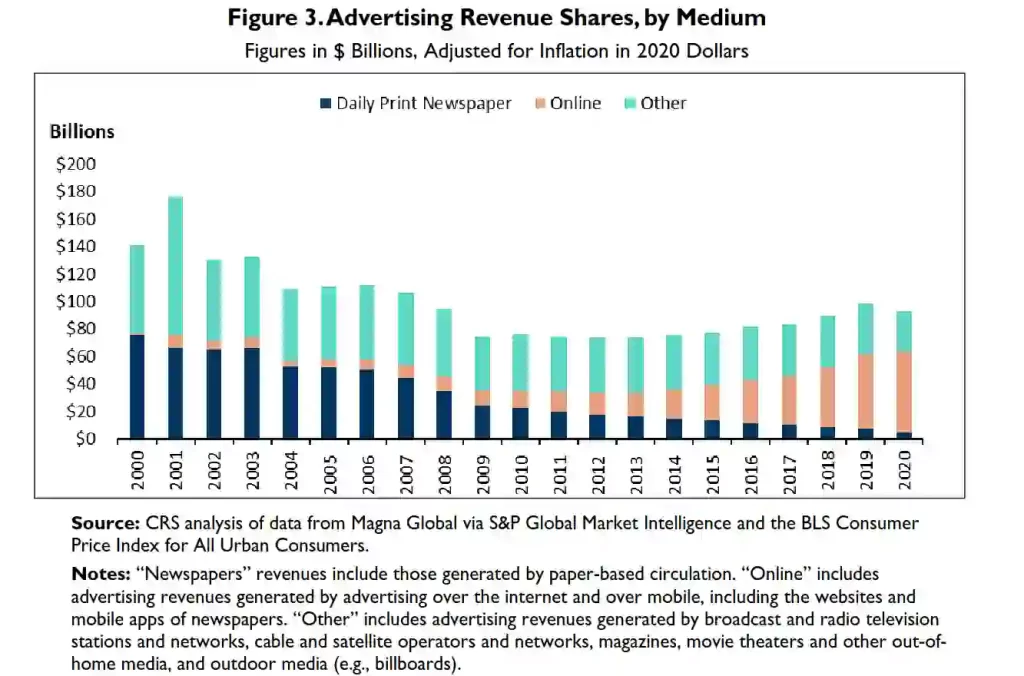

US advertising spending by medium: Newspapers had been losing advertising share for a long time, even before the internet.

As circulation flatlined, newspapers had to choose between lower profits and sacrificing quality. By the 1970s, the choice was made—newspapers sacrificed quality for profits. First, the newspapers cut editorial budgets, circulation, and production costs and fired reporters. Then, they cut the volume of news and increased the number of advertisements and advertising prices to maintain those ridiculous profit margins and please shareholders.

It no longer is a business, as publishers once joked, in which even the brain dead could make money.

Lou Ureneck

As competition disappeared, surviving newspapers raised ad rates. Between 1965 and 1975, ad rates rose 67 percent (remaining below the inflation rate); but between 1975 and 1990, as more newspapers became monopolies, rates skyrocketed 253 percent (compared with 141 percent for general consumer prices). — FCC Newspapers raised their ad rates three times as fast as inflation from the early 1970s to the late 1980s, the newspaper analyst John Morton told Barron’s in 1990.

Ryan Chittum—CJR

Then came the internet!

Even with the competition from radio and television, newspapers were still the only choice for targeted local advertising and classifieds. Despite declining circulation, newspapers commanded immense pricing power and continued to increase advertising rates from the 1970s to the 1990s. In this period, the large chains and conglomerates had a single-minded focus on maximizing margins and revenues. This made newspapers brittle, and when the internet arrived, they were like a tin can caught in a hurricane.

Even with the competition from radio and television, newspapers were still the only choice for targeted local advertising and classifieds. Despite declining circulation, newspapers commanded immense pricing power and continued increasing advertising rates from the 1970s to the 1990s. In this period, the large chains and conglomerates had a single-minded focus on maximizing margins and revenues. Newspapers had become brittle, and when the internet arrived, they were like a tin can caught in a hurricane.

As Kathryn Weymouth, the last Graham family publisher of the Washington Post, remarked when she passed the baton to Bezos: “If journalism is the mission, given the pressures to cut costs and make profits, maybe [a publicly traded company] is not the best place for the Post.”

Rodney Benson and Victor Pickard/The Conversation

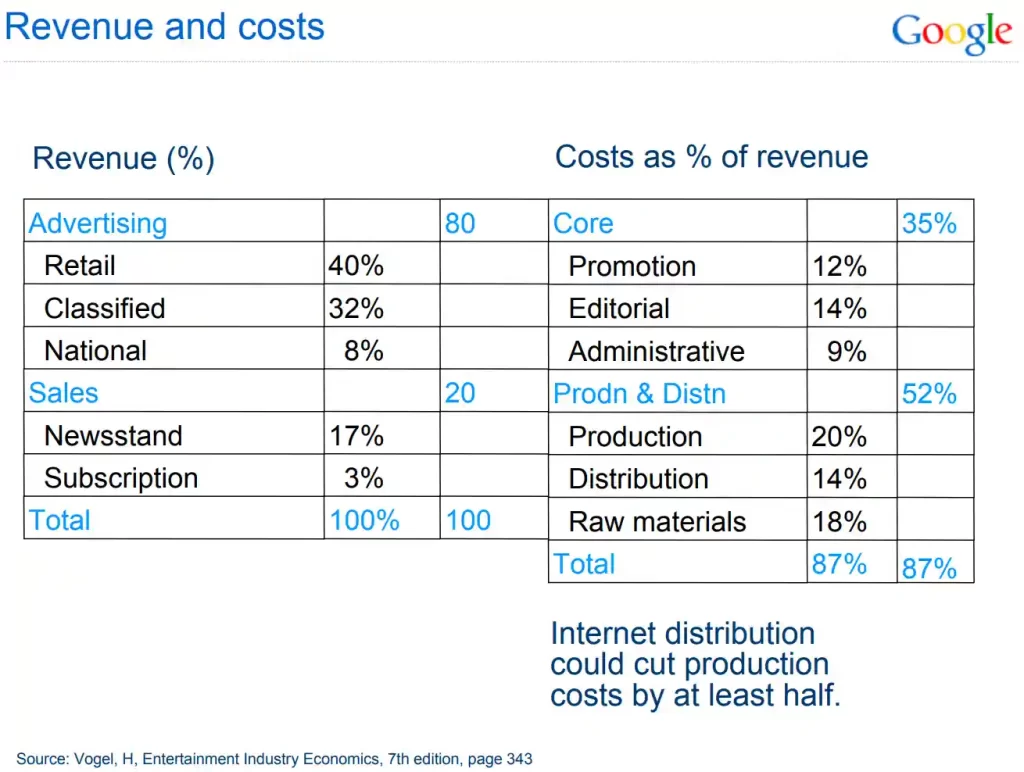

Unbundling

Newspapers enjoyed a privileged position as gatekeepers between readers and advertisers before the Internet. A newspaper was a bundle of news, sports, entertainment, weather, and games. You had to buy the entire paper regardless of your interests, and everybody got what they wanted. This is crucial to understanding how newspapers lost the plot. On the one hand, they aggregated advertisers; on the other, they aggregated readers’ attention.

So a key starting point for understanding the problem, which I think actually is a core part of the problem, is that the problem has been misunderstood, is that newspaper, the newspaper crisis, at least in places like the US and Australia, results from them no longer being as effective as a tool for attracting attention. And that really gets to the core, that the core business of newspapers was not to actually inform or provide news, but it was to attract attention for advertisers.

Amanda Lotz, media scholar and Professor at the Queensland University of Technology

Newspapers were always in the business of advertising. Advertisers weren’t subsidizing quality journalism; they were buying the attention the newspapers aggregated. Before the internet, newspapers were the best medium to reach consumers, and that was all that mattered to advertisers. For a long time, the interests of the newspapers and the advertisers were aligned, and everybody was happy.

Then came the internet. It unbundled the newspaper and destroyed this arrangement.

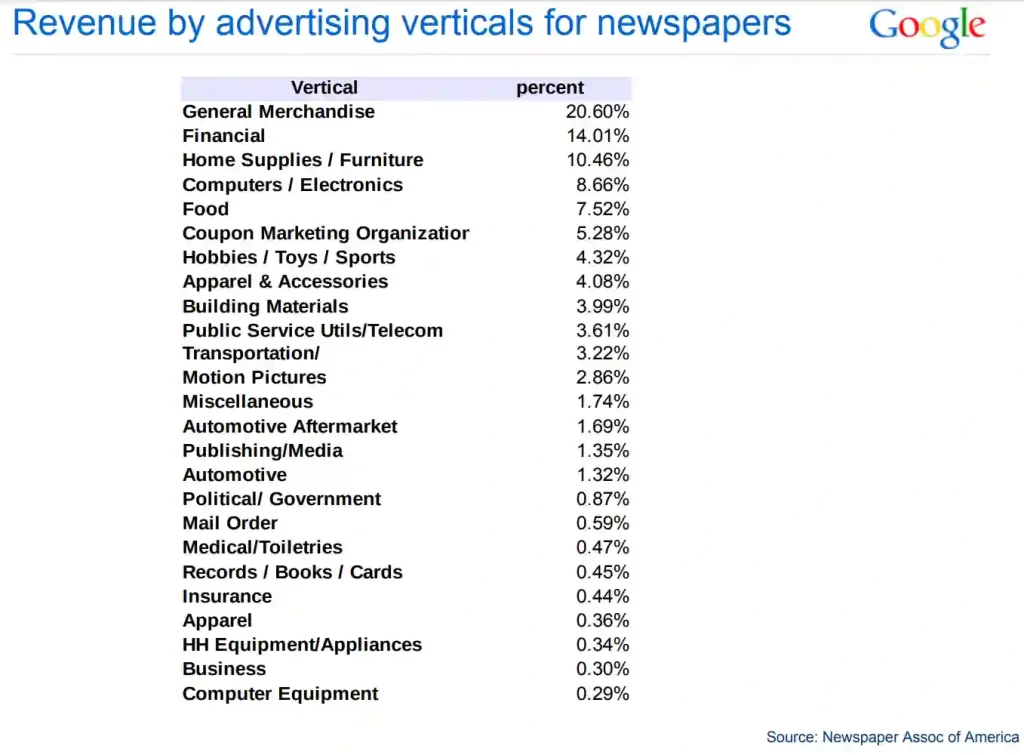

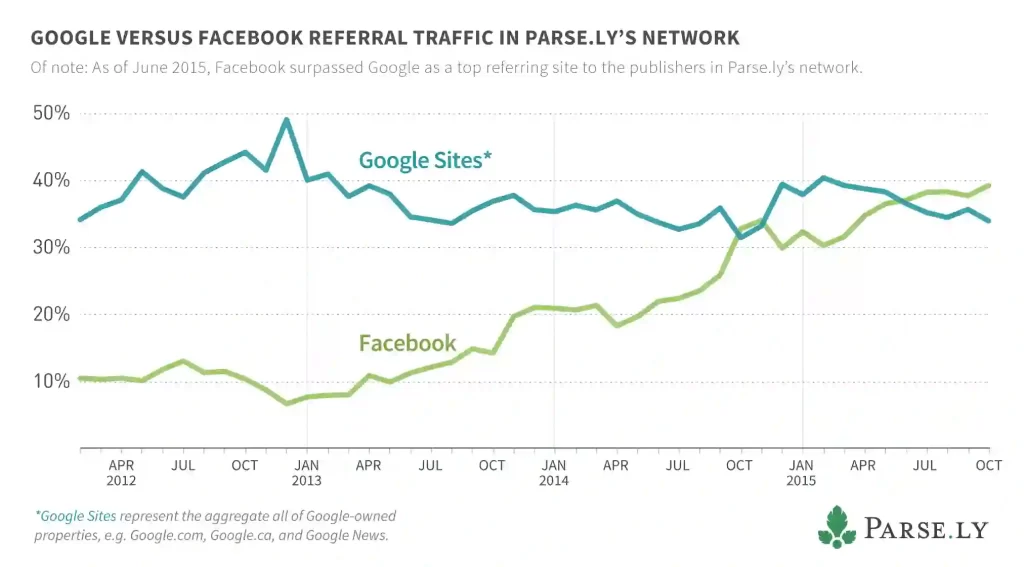

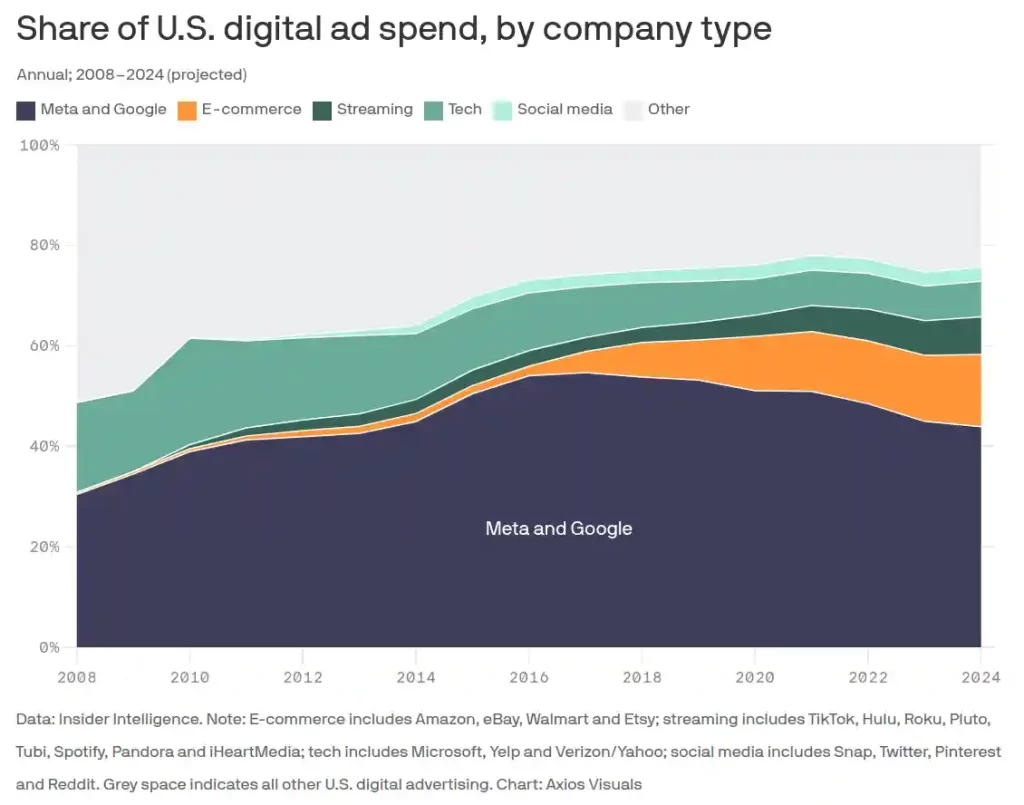

Advertisers didn’t have to rely on newspapers to reach audiences because the newspaper was a dumb bundle. Advertisers could only target consumers based on the geographies that newspapers operated in. But internet companies like Google offered a far superior advertising proposition. Advertisers could slice and dice audiences and micro-target consumers.

The readers no longer had to buy the entire newspaper bundle; they could read whatever they wanted online. The internet stripped the news bundle to its atomic unit—the news story. Readers no longer had to rely on publishers like The New York Times and Gannett to assemble a news bundle. In a sense, everybody on the internet could be their own publisher. They could build their own bundle of what they wanted to read, watch, and listen to. They could read about politics in The New York Times, sports on ESPN, and entertainment on Variety. This was a boon for readers, not so much for newspapers.

Publishers also typically engage in horizontal integration, bundling hard news with horoscopes, gossip, recipes, sports. Simple inertia meant anyone who had tuned into a broadcast or picked up a publication for one particular story would keep watching or reading whatever else was in the bundle. Though this was often called loyalty, in most cases it was just laziness—the path of least resistance meant that reading another good-enough story in the local paper was easier than seeking out an excellent story in a separate publication.

The web wrecks horizontal integration. Prior to the web, having a dozen goodbut-not-great stories in one bundle used to be enough to keep someone from hunting for the dozen best stories in a dozen different publications. In a world of links and feeds, however, it is often easier to find the next thing you read, watch or listen to from your friends than it is to stick with any given publication. Laziness now favors unbundling; for many general interest news sites, the most common category of reader is one who views a single article in a month.

Post Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present

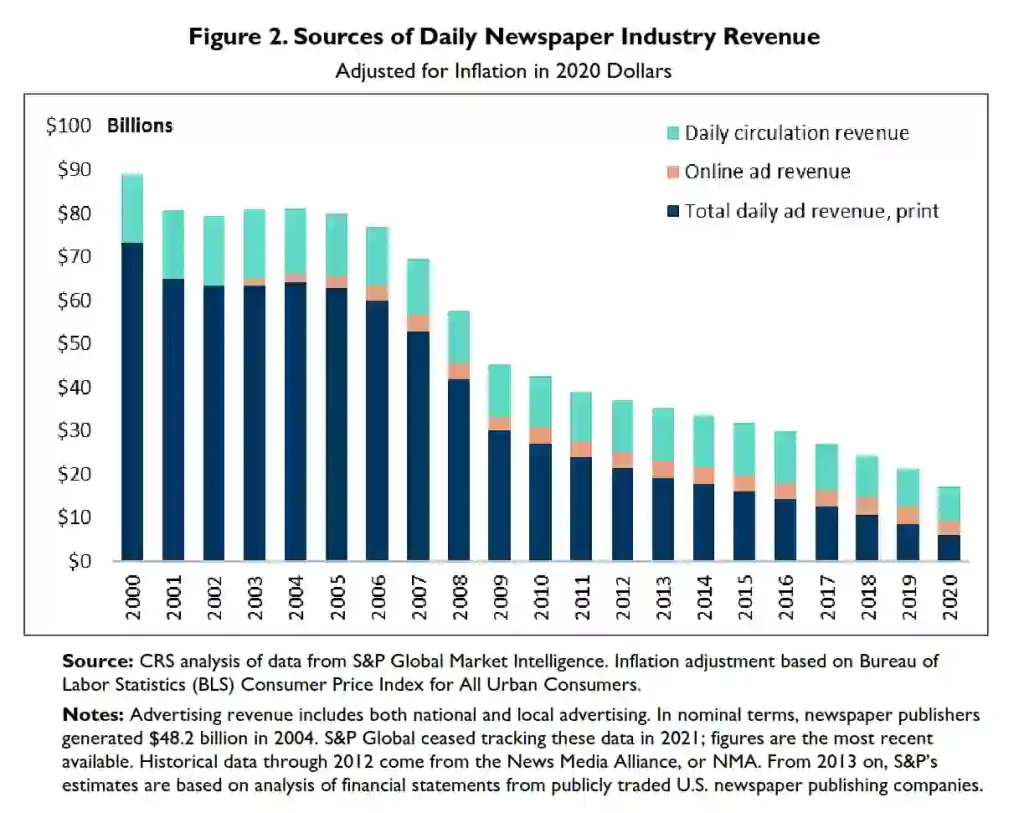

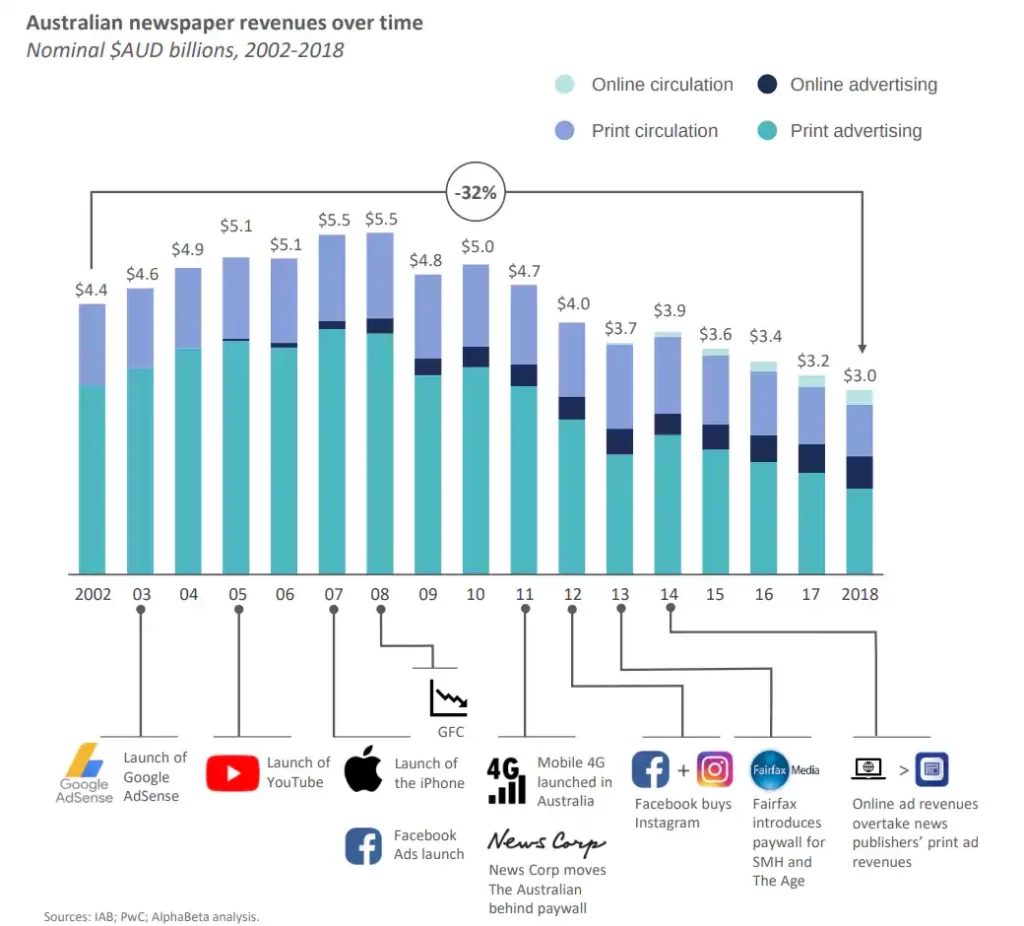

Classified advertisements, such as hiring ads, real estate listings, and automobile sale advertisements, were the biggest casualties of the internet. Newspapers charged exorbitant prices for a few lines of text, and these ads accounted for 40–50% of newspaper advertising revenue. Classified advertising revenues peaked in 2000 at $19.6 billion as sites like Craigslist, Monster, Zillow, eBay, and Cars.com became popular. By 2010, classifieds revenues had dropped by 70% to $5.6 billion.

Any industry that saw 40–50% of its revenues vanish should have died, but the newspaper industry continued to hobble along. It shows the extraordinary position newspapers were in. As classified revenues started dropping, so did other print advertising. For a long time, brands advertised in newspapers because they had no choice. They had no clue if people who bought newspapers cared about the ads. Since newspapers were local monopolies, businesses had no choice but to advertise. But, on the internet, advertisers paid only for the ads consumers saw. This was a revolutionary shift, and there was a sharp decline in print advertising.

As Professor Amanda Lotz put it, the internet stripped away the profitable parts of the newspaper bundle and left the publishers with the most expensive part—the news.

Internet communication technologies have unbundled the newspaper the internet has improved replaced or at least affected just about every part of the bundle and done so in different ways. The key here, where i’m kind of going with this argument is that it used to be that an accumulation of things added value to a newspaper and bit by bit the internet has stripped many of them away and what is left is largely the most expensive part and what is missing are all the different ways that used to pay for it.

Amanda Lotz

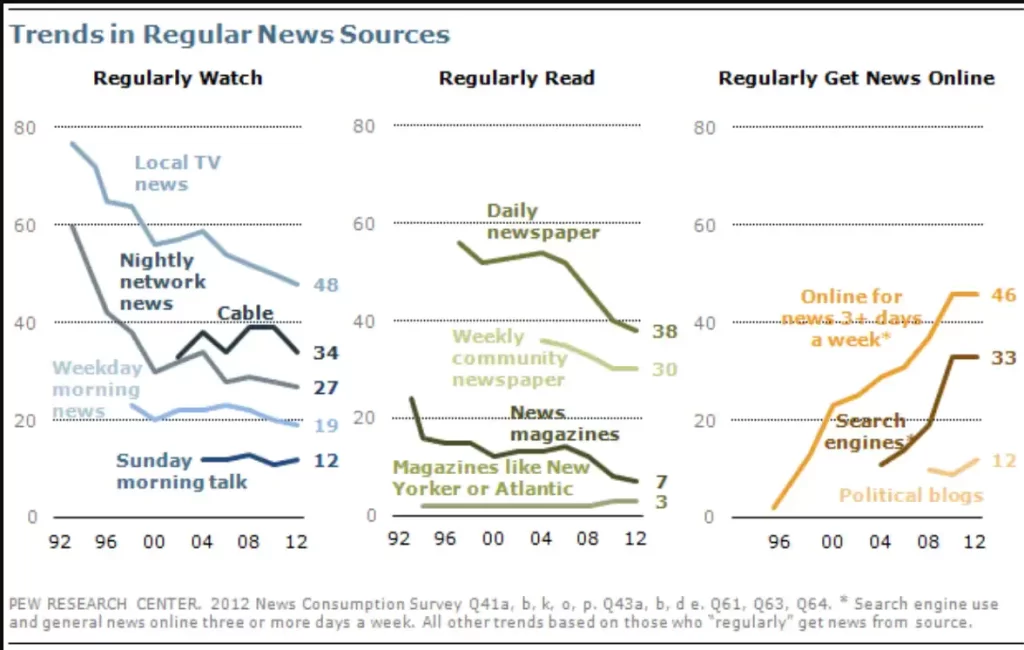

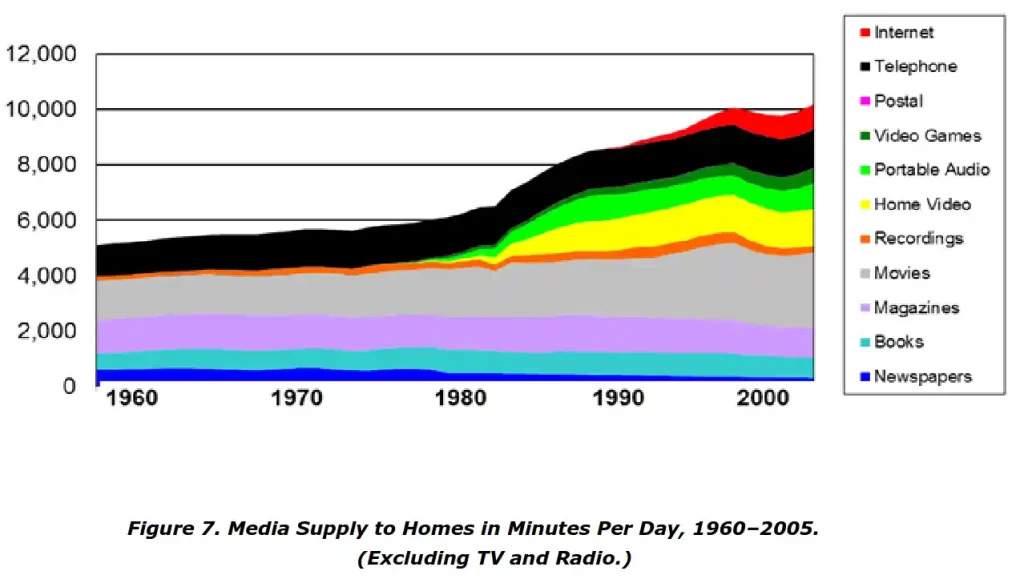

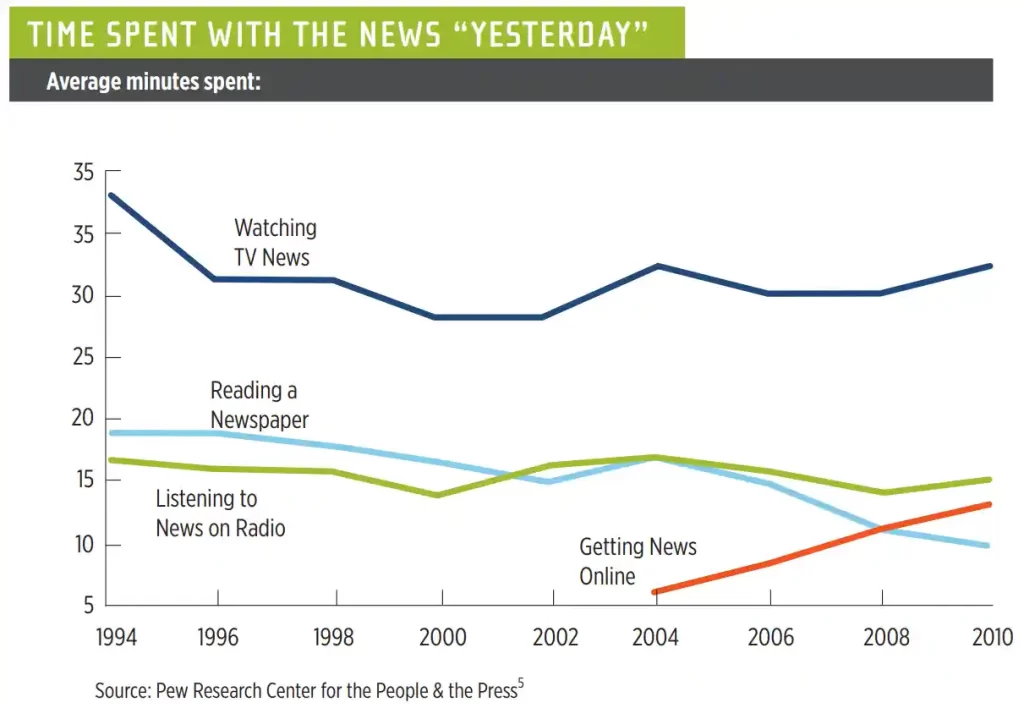

Newspaper readership was declining long before the internet, as radio, television, and other mediums started competing for attention.

By the turn of the century, Americans had more media competing for their attention than at any point in history. Sure, news mattered, but videos and movies mattered more.

Within the span of a single human generation, people’s access to information has shifted from relative scarcity to surplus.

Vin Crosbie

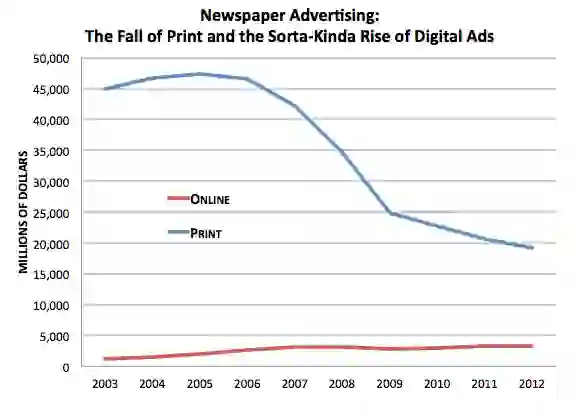

The newspaper industry’s inflation-adjusted revenues peaked at $89 billion in 2000 and plummeted 80% to $18 billion in 2020. Newspaper subscription revenues also took a large hit, dropping by over 50% from $15.8 billion in 2000 to $7.8 billion. Online advertising revenues reached $3.3 billion in 2020, but they were a drop in the bucket compared to the losses in subscription and print advertising. Newspapers were trading “print dollars for digital pennies.”

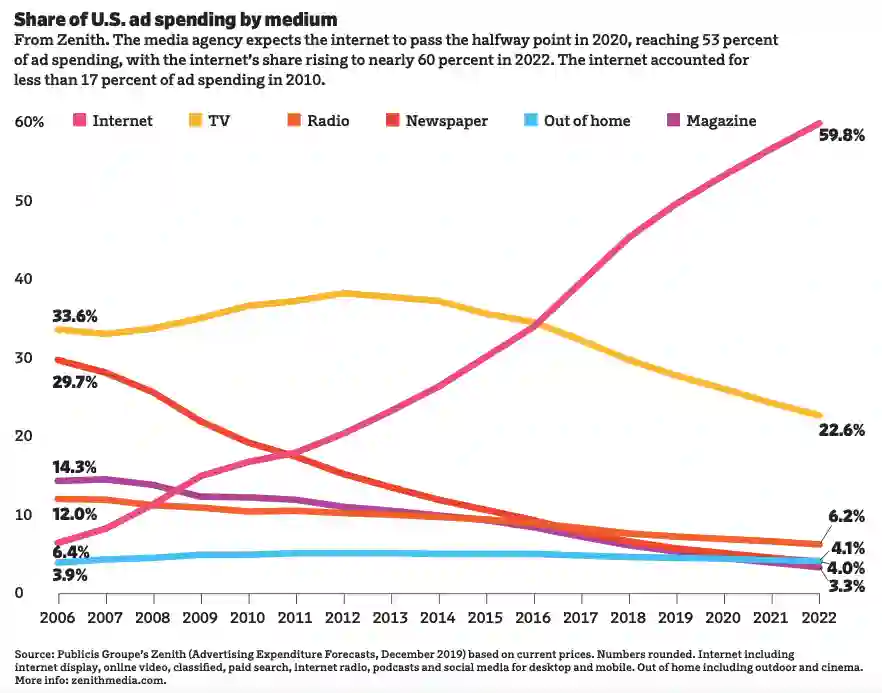

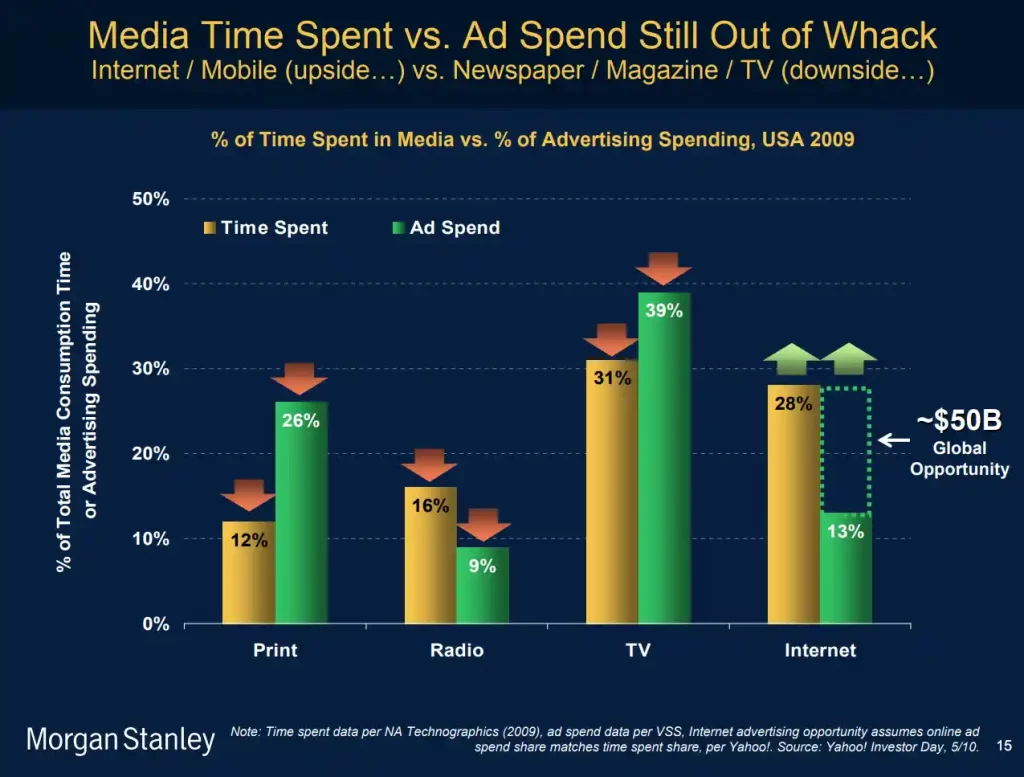

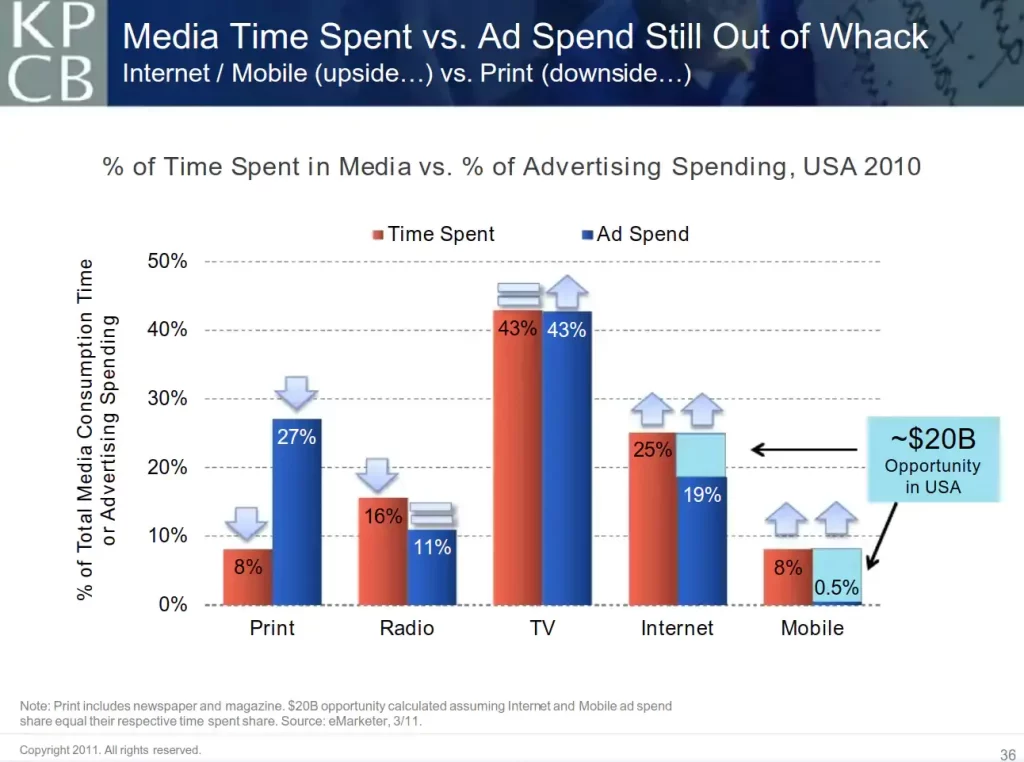

The internet caused a dramatic shift away from traditional advertising channels. Print and radio were the biggest losers.

The internet didn’t kill newspapers. Newspapers were stabbed by radio, television, and other economic shifts. As they lay bleeding on the ground in a dimly lit parking lot, the internet walked in and tripped over something in the dark. The internet looked down, picked up the object it had tripped over, and held it up in the light—it was the bloody knife that had been used to stab newspapers. As the shocked internet stared at the knife, the cops rushed to the crime scene, and the internet was accused of the stabbing.

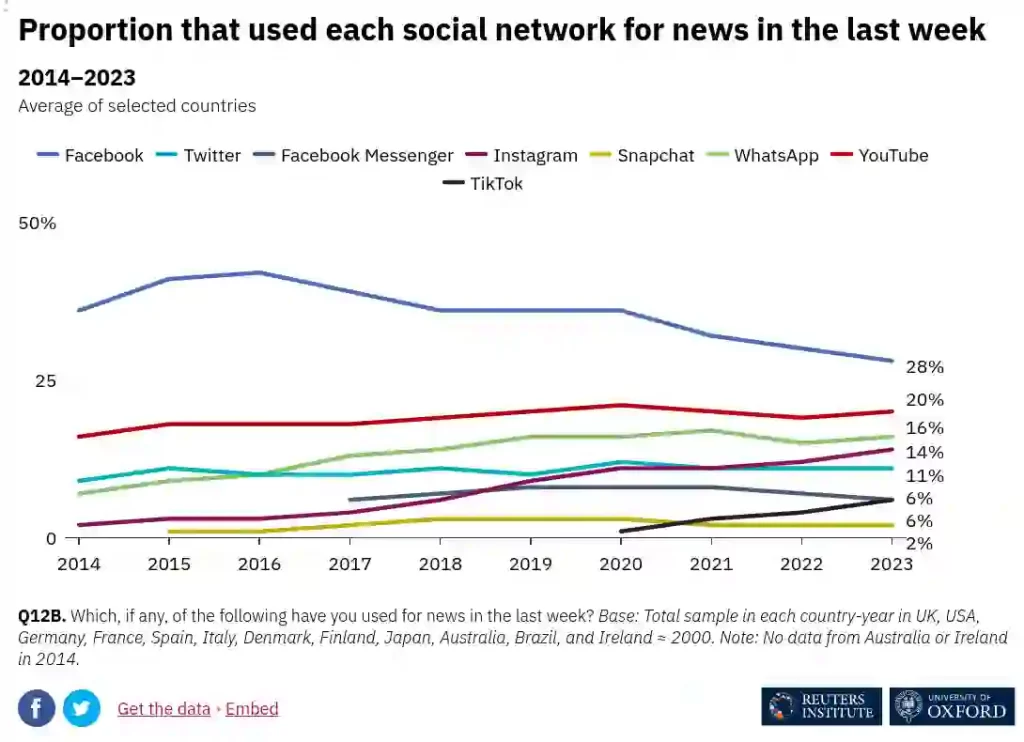

What killed the newspapers wasn’t the internet, but a change in how people consumed information coupled with a generational shift in attitudes. Each successive generation has adopted a new medium to get its news: it started with radio, television, cable television, followed by the internet, social media, and so on. As I write this post, version one of social media is dying; what comes next is anyone’s guess.

Newspapers ain’t hip enough.

News deserts

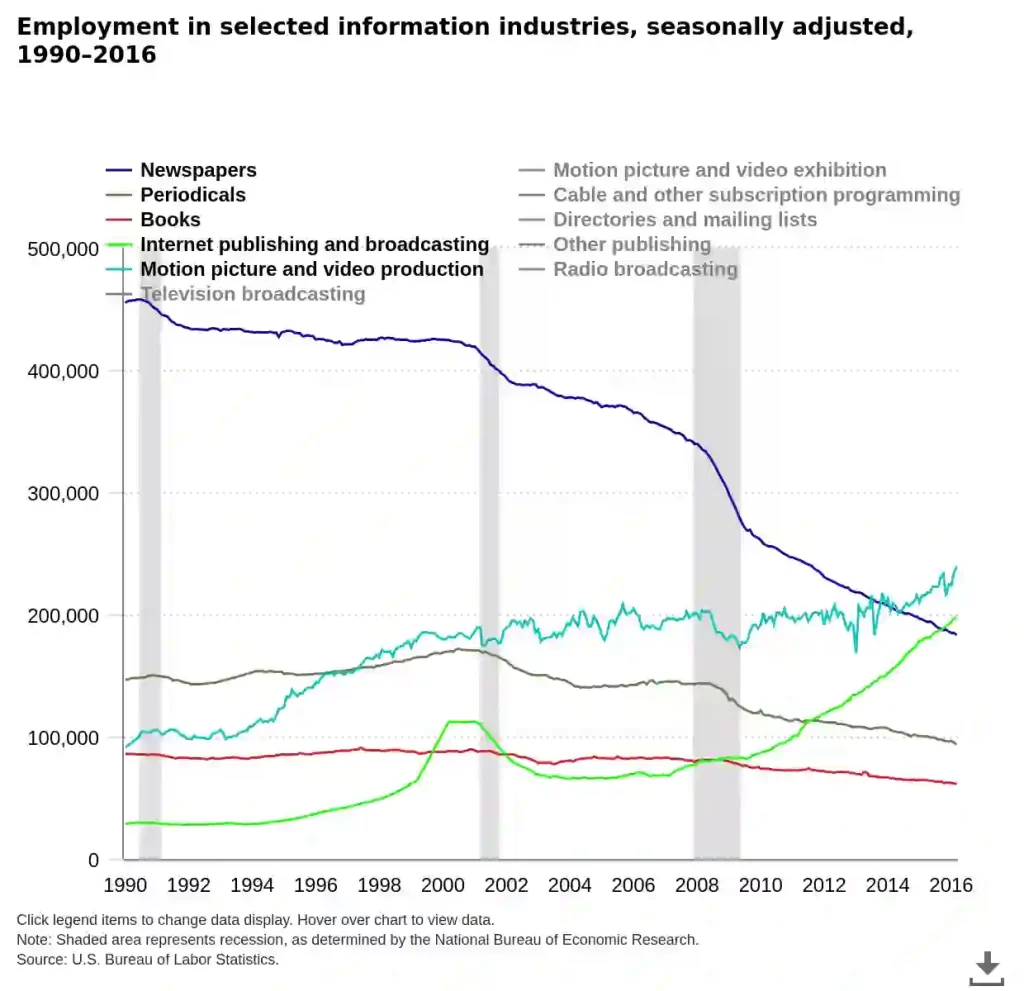

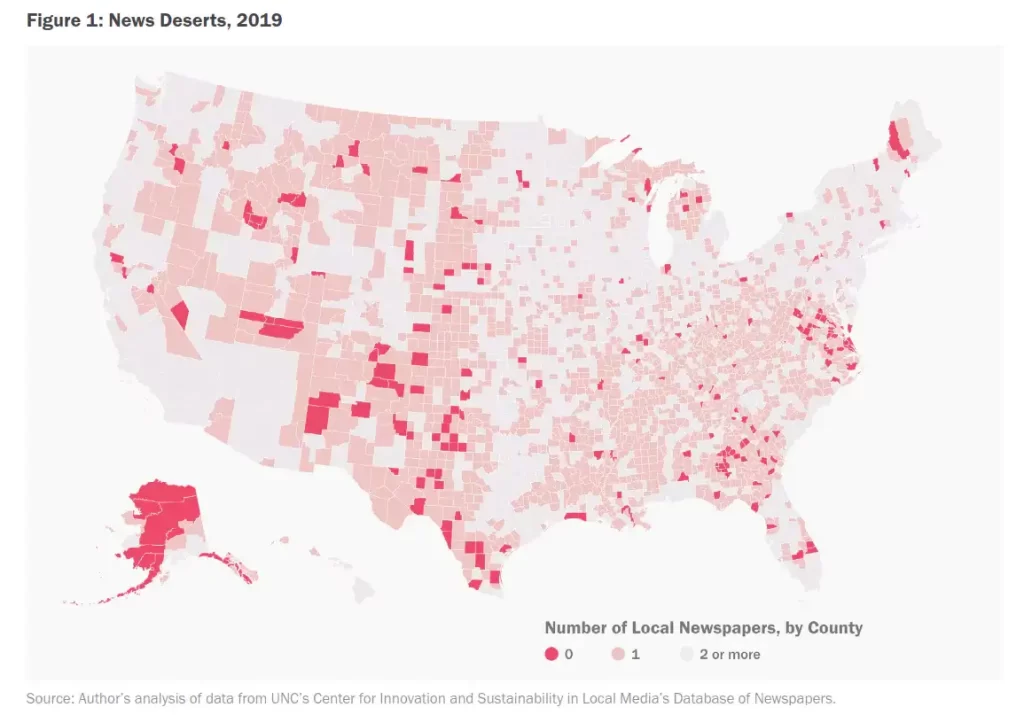

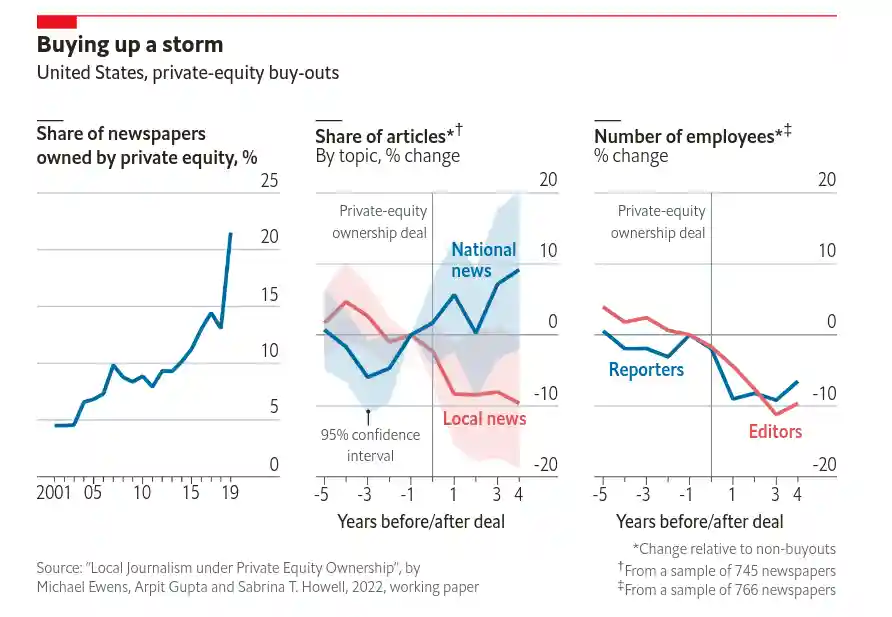

The internet affected local newspapers the most, leading to the closure of over 2,000 newspapers. At one point, newspapers were shutting down at a rate of two per week. The number of reporters per 100,000 people dropped by 62%, and the ratio of reporters per $100 million spent by state and local governments declined by 67%. The total revenue lost by newspapers amounted to over $40 billion.

As newspapers closed, small towns and counties transformed into news deserts. Thousands of local communities don’t have any news coverage today. Without vigilant reporters, local governments, notorious for corruption, have been left unsupervised.

The death of local newspapers is not good for democracy. Numerous studies have shown that the loss of local news leads to increased municipal borrowing costs, reduced civic engagement, lower voter turnout, and a lack of political accountability. Newspapers are like sunlight—they are the best disinfectant, especially at the local level.

How did the newspapers respond to the internet?

There are two broad narratives about how newspapers responded to the arrival of the internet:

- They were sitting ducks that didn’t innovate. They were extracting rent even as the internet ravaged their business.

- The newspaper companies were anything but lame ducks, and they were far more innovative than people gave them credit for. In their fear of getting disrupted, they went overboard on adopting digital and sacrificed print.

Narrative 1

The newspapers were dinosaurs clutching their printing presses with a death grip while staring at the internet like a hound foaming at the mouth with its fangs out, ready to shred it into keema.

The narrative that newspaper companies were useless and incapable of innovation has become a truism. The story is that they were a classic example of disruptive innovation. The cool kids kneecapped the arthritic incumbents with a cricket bat. But the reality is that the story of newspapers getting disrupted is a little more complex. History shows the newspapers were anything but dinosaurs waiting to be hit by an asteroid. They were more innovative than they get credit for. Before the internet hit the mainstream, there was existential paranoia about being disrupted among the major papers.

In the early 1990s, Roger Fiddler conceptualized a tablet for reading news at the newspaper giant Knight Ridder. The same Knight Ridder spent $50 million to develop a video-text service called Viewtron in the 1980s. It was a dedicated terminal on which you could read news, check airline schedules and bank balances, and order a meal. During the same period, most major newspapers offered audio-text services. Subscribers called a phone line to get news, horoscopes, race listings, and sports scores, among other things. They also offered news over fax and were early adopters of private internet networks like AOL and Compuserve, but the internet was too small at that point.

This excerpt from a phenomenal study by Iris Chyi, a media scholar, further illustrates how nimble newspapers were:

Contrary to general impressions, most U.S. newspapers were not slow in adopting Internet technologies for news delivery. The Web did not become publicly accessible until 1991. Soon after Mosaic (one of the earliest Web browsers) was released in 1993, the Palo Alto Weekly went online in January 1994 as the first Web-based newspaper. By May 1995, as many as 150 U.S. dailies offered online services—when less than 1% of the U.S. population had Web access (Carlson, 2003). The New York Times went online in January 1996, and numerous newspapers followed suit. By 1999, more than 2,600 U.S. newspapers were providing online services (Editor & Publisher Interactive, 1999). However, by 2003, the industry consensus was that no business model had been found (Carlson, 2003).

Iris Chyi

Meanwhile, Rusbridger was thinking about the Guardian’s digital future. In 1994, a year before he became editor, he visited Silicon Valley. “I came back and wrote a memo to Peter saying the Internet was the future,” Rusbridger recalls. “I told Peter this would change everything and we had to explore it.” Emily Bell, the Observer’s business editor at the time, remembers having dinner with Rusbridger and others during the Edinburgh TV festival in August, 1999, and telling him that changes he’d made to the paper’s Web site were inadequate. She prodded him to move more aggressively into the online world, with more breaking news and analysis; in 2001, he placed her in charge of turning the Web site into a vibrant online paper.

Ken Auletta | The New Yorker

The question then is, How dedicated were the newspapers toward going digital? Even a cursory reading of history shows that most newspapers knew what was coming. They were experimenting with digital technologies on the eve of the internet. Were the experiments half-hearted attempts with the shiny objects of that era or attempts to appease people agitating for change? Whatever the case, you can’t fault the newspapers for being complacent.

Narrative 2

The newspaper publishers, driven by lust, fell for the siren song of the internet. They ignored their faithful print editions and cheated on the print editions. Online editions earned pennies compared to print dollars. Newspapers ended up in limbo where print was fast dying, and digital was disappointing. The newspaper industry made a mistake by going all in on digital. Despite the sharp declines, print was still generating all the revenues. This is the provocative view of some media studies scholars like Iris Chyi and industry observers.

As newspaper firms were amazed by (and obsessed with) each and every digital technology, the recession hit and put many companies in serious financial difficulty. Driven primarily by fear and uncertainties at this stage, newspaper firms acted upon the unchecked assumption about the all-digital future and responded to their financial woes by slashing resources for their print product to continue their incomplete transition online. But the truth is, most newspapers are stuck between an unsuccessful experiment (for their digital product) and a shrinking market (for their print product). Even more embarrassing is the fact that the (supposedly dying) print edition still outperforms the (supposedly hopeful) digital product by almost every standard, be it readership, engagement, advertising revenue, or paying intent.

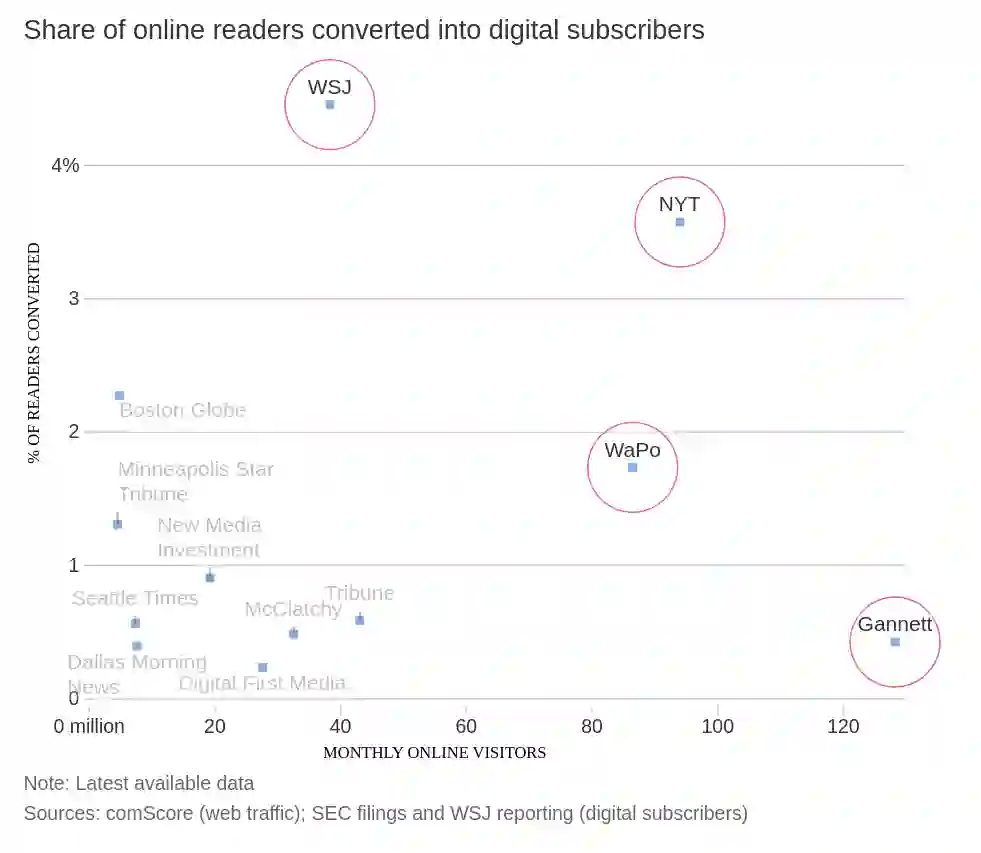

It might seem like betting on digital was a mistake if you look at the online subscriber numbers of major news publishers.

But continuing to invest in print when the bottom of the print advertising market fell off wouldn’t have helped. Even god couldn’t have made print advertisements competitive compared to digital ads.

This view led to a fascinating back and forth between Iris and Joshua Benton, founder of the Nieman Journalism Lab. Josh believes newspapers couldn’t have done much, and the more I look at the numbers, the more I agree with him. I don’t think newspapers could’ve done anything that would’ve allowed them to transition to the digital age unscathed. The internet changed how people consumed information, and disruption was inevitable.

As Alan Mutter, a veteran media executive, wrote in response to Iris Chyi’s the paper:

It’s hard to imagine how newspaper companies can survive over the long term if they put their primary focus on print.

Which narrative is right?

The one that makes the most sense to you.

Did the newspapers do everything they could to prepare for the internet?

No.

In 2019, historian Jill Lepore wrote a phenomenal article titled “Does Journalism Have a Future?” In the post, she recounts two incidents involving The Washington Post and The New York Times that now, in hindsight, seem insane. The Washington Post let go of an opportunity to invest in Facebook. It also refused to back the founders of Politico, one of the greatest online publishing success stories. The New York Times, on the other hand, refused to invest in Google. It’s easy to extrapolate from these anecdotes and paint the newspapers as dinosaurs, but that’s not the point. At the very least, they knew about internet upstarts threatening their existence. If nothing, this shows their myopia. They could’ve tried harder to adapt to the new era. I’m conscious that it’s easy to exaggerate these things in hindsight.

Why didn’t the newspapers ever put up a decent fight against search giants like AOL, Yahoo, and Google? This question has bothered me for a long time. Newspapers had some idea of the threat that internet companies posed. Yet, the industry let the internet upstarts punch them in the face and walk away.

Some newspapers did try. In 2011, the Tribune, Gannett, Hearst, and The New York Times tried to pool their advertising inventory to compete against Google. The partnership shut down two years later. The Guardian, CNN, Reuters, The Economist, Financial Times, and others formed a similar advertising alliance that ended in 2021. In 2016, USA Today, The Houston Chronicle, The Miami Herald, and The Los Angeles Times formed a similar partnership. There were several other advertising partnerships between competing publishers with varying degrees of success, but they were late by a decade. By the time of the first advertising partnership between news publishers in 2011, Google had generated $38 billion in revenue.

As the internet arrived, newspapers were flush with cash. They had a chance to build advertising offerings that could’ve, at the very least, been distant alternatives to Google and Yahoo.

The disastrous error that newspapers made early in our digital lives was treating online advertising as a throw-in or upsell for their print advertisers. Helping businesses connect with customers was always our business. We were facing new technology and new opportunities and we did next to nothing to explore how we might use this new technology to help businesses connect with customers.

Steve Burttry, director of Student Media at the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University.

Not all experiments were in earnest. In response to the internet, newspapers just started to upload articles online in a haphazard way. They were too scared that digital would cannibalize print. In 2017, Melissa Bell, the co-founder of Vox Media, gave the Reuters Memorial Lecture on how we broke news and how to fix it. During the discussion, the legendary Marty Baron, the former editor of The Washington Post and The Boston Globe, made some interesting comments:

I’m not sure that if we had done any one thing, things would have turned out all that differently, to be honest with you. There were a lot of efforts to deal with the internet.

So there were a lot of efforts, I mean not all that we should do, certainly with regard to classified advertising, people were aware of what Craig Newmark was doing. There were a lot of people saying, why aren’t we doing this? And obviously in classic fashion, the industry was worried about doing that, going full bore because they were worried about undermining their pre-existing business model, which is the classic story of disruption, right? So, so, I think it’s, we made a lot of mistakes.

I think I always say that what we’re talking about here is a new medium. It’s not the same medium, all right? So we had print, then we had radio. It’s different. The way you communicate on radio is different from the way you communicate in print. Then we had television. The way you communicate on television is different from the way that you communicate on radio and the way you communicate in print. And along came the web, and what did we do? We just put up print stories. And then that didn’t work. And then we said, well, okay, let’s put them up faster. And we put them up faster and that didn’t really work. And what we’re talking about now is just a different way of communicating.

Marty Baron

There was a certain collective delusion about the effectiveness of a newspaper bundle before the internet. Newspapers almost made it seem like readers looked at all advertisements in a paper. Advertisers had to go along with the crazy notion because they had very few local advertising alternatives. This enabled local papers to become monopolies.

Print publishers used to tout the “pass-along audience”—people who didn’t buy a magazine or newspaper but picked it up in, say, a dentist’s office, and could therefore be counted as readers. Advertisers were often skeptical of the numbers, which depended on surveys of readers trying to remember if they read a publication they didn’t pay for.

CJR

Newspapers enjoyed tremendous pricing power throughout the 20th century. Owning a printing press was a license to print money. The period from the 1950s was the golden age for newspapers, as they took in boatloads of cash. Newspapers thought this would go on forever and forgot the fact that this golden era was an aberration.

Speaking in a panel titled “Will there be journalists in 2030?” at the International Journalism Festival in 2017, here’s what George Brock, a former journalist and professor of journalism, said:

In the late twentieth century, we had a period in journalism in which income from print and terrestrial television was very solid and relatively assured. It convinced an entire generation of journalists, my generation, roughly speaking, that all this would continue roll forward on wheels indefinitely. That is historically complete nonsense. Every other area of journalism has been improvisational, volatile, risky and littered with the wrecks of projects that don’t work. So we have to be weird to get used to threats coming at us might be artificial intelligence. It might be virtual reality. It might be ad blockers. It might be anything. They will come at us in a regular stream. Get over it.

Do people care about the news?

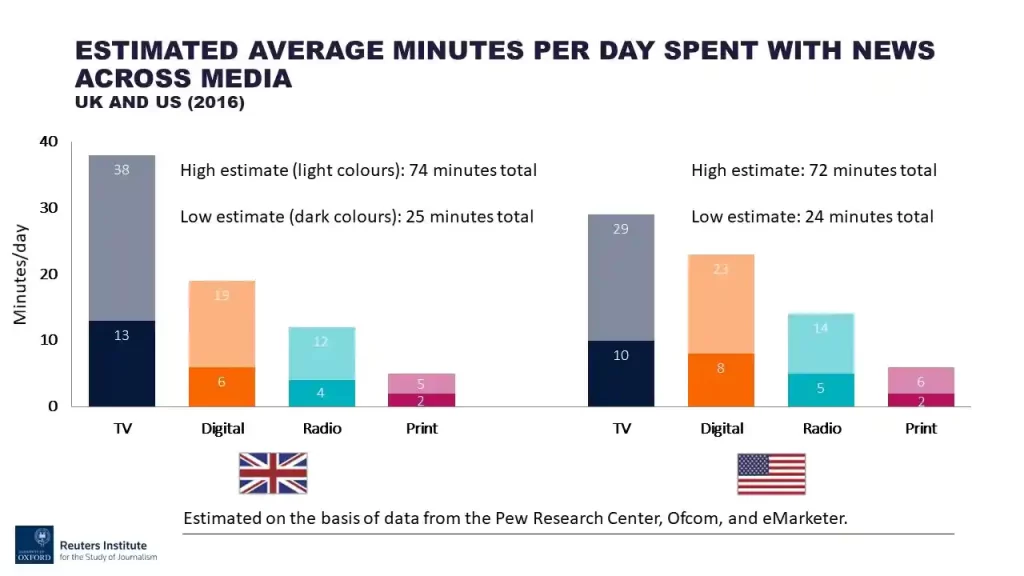

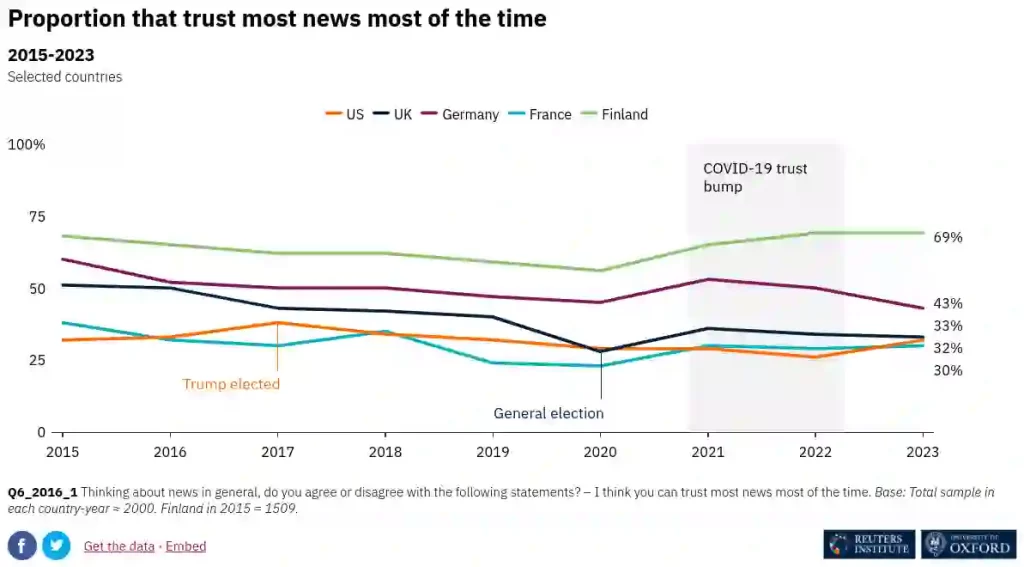

The internet exposed the inconvenient truth that most people don’t care enough about news to pay for it. There isn’t a lot of good data on news consumption habits, but the available data gives you a directional idea. The Reuters Institute published a study tracking online news consumption during the 2019 UK General Election. They found that the average user read 16 minutes of news in a week, which made up only 3% of the total internet time, even during the election.

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, the director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, published another estimate. The time spent on online news ranges from 6 to 23 minutes a day.

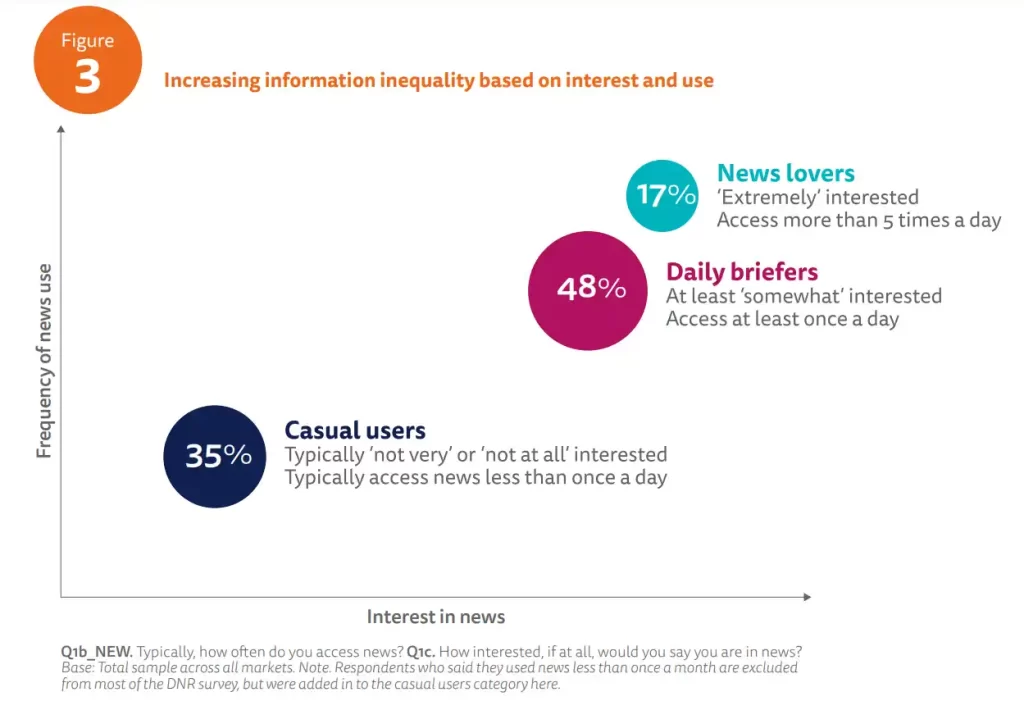

Another report from Rasmus Nielsen and Meera Selva found similar numbers. Only 17% of users access news more than five times a day. 48% read news once a day.