A few things I learned this week.

The post-2008 period was like a rave party for the financial markets. The central banks around the world had the hottest parties with cheap tickets, booze, and food. The parties were all the rage for well over a decade. But, it was 5 AM in 2020, and the party had become more of an after-party. The party people were tired and wanted to go to sleep. But suddenly, the central bankers decided to keep the party going by offering free booze and free money. Suddenly, the sleepy after-party became a raging after-after-party.

Every party has its share of crazy and nutty characters, and this party was no different. One of the craziest characters at this party was the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). SPACs might have been late to the party in 2020, but they more than made up for the lost time with their craziness on 5X leverage. As the name implies, they are quite special. SPACs are shell or blank-check companies that list on the stock exchanges to raise money to acquire or merge with existing companies.

In finance, you can look at everything from the lens of arbitrage—easy vs tough, opaque vs transparent, short term vs long term, dumb vs smart. In a way, SPACs take advantage of all the worst parts of all these arbitrage opportunities. If a company wants to go public, it has to deal with a lot of regulatory hassle, and there are a lot of restrictions on what it can and can’t say and do. But what if you still want to go public but avoid most, if not all, the hassles of going public? Enter SPACs. A SPAC, even though it walks like an IPO and talks like an IPO, isn’t an IPO but rather a merger.

The rules and regulations for going public in the US are quite cumbersome. But SPACs aren’t really IPOs, but rather mergers and the rules for mergers are much less cumbersome compared to IPOs. There’s also a lot less liability risk. Think of SPACs as backdoor IPOs.

Companies that IPO typically don’t include future projections in their offer documents because they can be sued if investors don’t like them. But SPACs, on the other hand, can make projections because they aren’t IPOs. US mergers have a safe harbor provision that shields them from liability over forward-looking statements. SPACs take advantage of this. In general, there’s also less liability risk for all the parties involved in SPACs. And SPACs have made full use of this arbitrage opportunity to make reality-defying projections that would make astrologers look like scientists and statisticians.

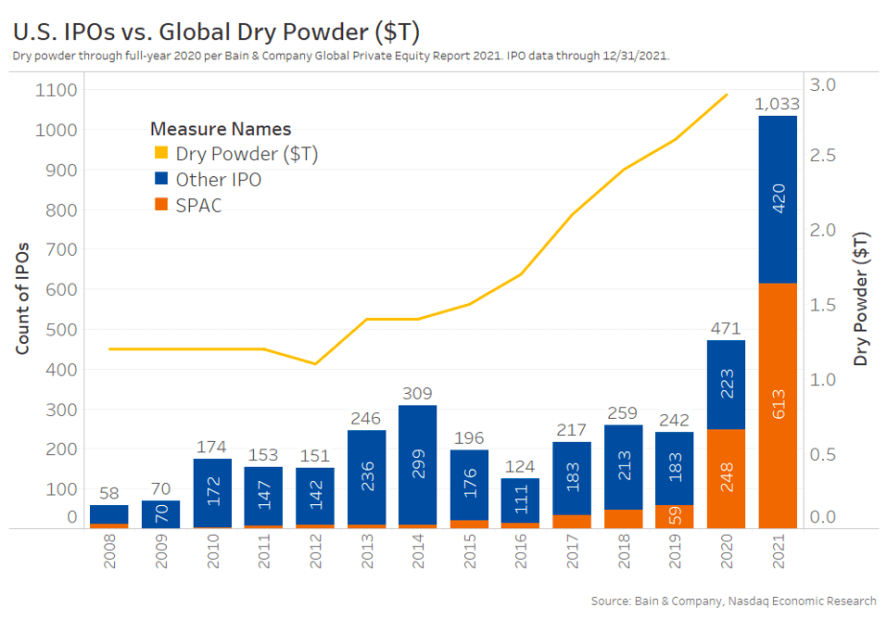

And SPACs have made full use of this arbitrage opportunity to make reality-defying projections that would make astrologers look like scientists and statisticians. Given the lesser hassles in 2020 and 2021, we saw a SPAC boom, the likes of which we’ve never seen before.

The reason for the boom? Another arbitrage opportunity—opaque vs transparent and dumb vs smart, i.e., wealth transfer from the informed to the uninformed. The typical narrative is that SPACs are faster and cheaper than traditional IPOs, but that’s just that—a narrative. The reality is that SPACs are complex structures. They’re much costlier than IPOs and much more lucrative for the sponsors of SPACs, investment bankers, lawyers, PIPE financiers, and pretty much everybody except retail investors1, 2, 3. In most SPACs, retail investors typically get heavily diluted right out of the gate.

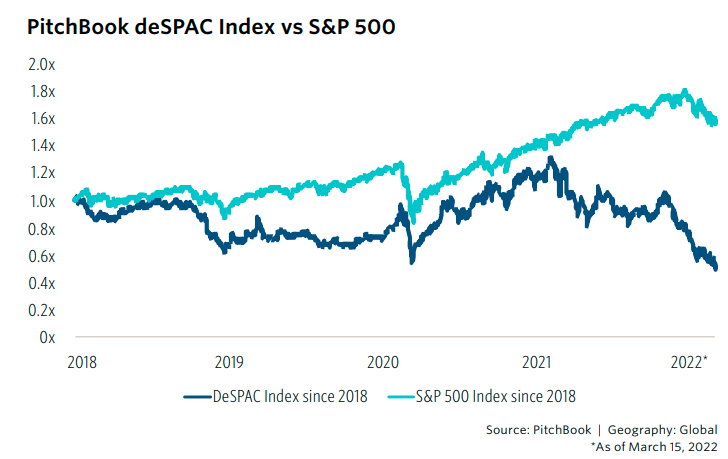

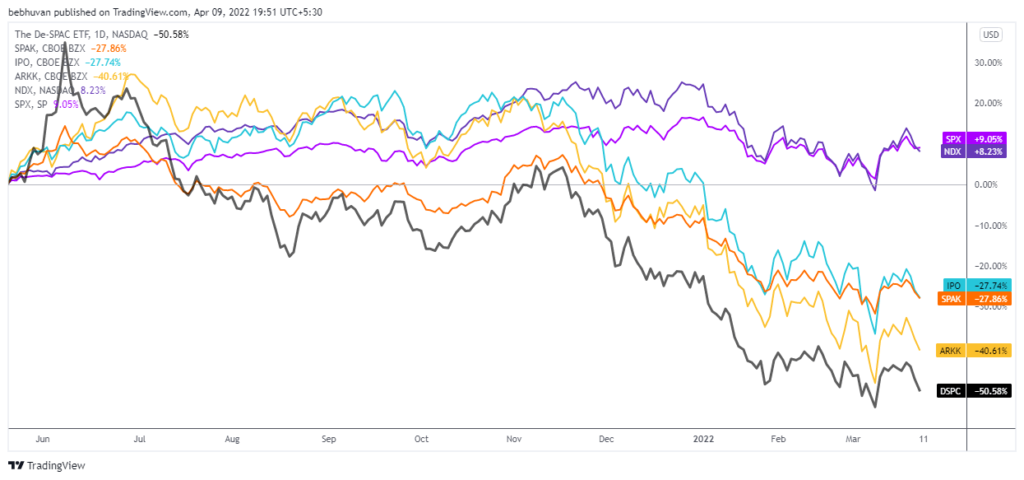

Predictably, this hasn’t worked out well for most investors. Pitchbook published a note on SPAC performance, and this chart is a sight to behold. It should probably be sold as an NFT because it’s art!

Typically, sponsors of SPACs have about two years to find a deal. The other important thing is that SPAC sponsors get 20% of the SPAC shares for almost free for taking the trouble of creating the SPAC and finding deals.

The Lucid deal and the merger of online education company Skillsoft with Churchill Capital Corp II netted Klein $690m, while Palihapitiya made $408m from the promotes of his two Spac deals last year, according to Spac Research data.

FT

So, the incentives are heavily skewed right from the start. What ended up happening is that SPACs became the go-to vehicles to take worthless and, in some cases, downright fraudulent companies public. If you look at SPACs that have acquired or merged, you’ll see companies with wildly optimistic projections, flawed business models, and multiples that were high on drugs. There have also been downright frauds. Most of these companies wouldn’t have been able to pull off a traditional IPO.

Now that we are in an inflationary environment with rising interest rates, it’s the perfect storm for these companies, and they’ve been massacred. Growth investing has fallen all the way from the moon into the Grand Canyon.

Given the craziness on steroids and other drugs in the SPAC market, the SEC has been expressing concerns over the last couple of years. It looks like they’ve decided to finally do something. In March, the SEC proposed new rules that bring SPACs on part with IPOs, and increase liabilities for all the parties involved. In a way, this was long overdue. These rules Though SPACs may not vanish altogether like they did post-2008, issuance is bound to come down. SPACs have been deSPACed—pun intended.

There’s also a story here about financialization and democratization. Contrary to what the “experts” say, increased democratization and financialization in the markets aren’t an unalloyed good as they are made out to be. Some things should just be for the rich and the “sophisticated” investors to gamble. As I was reading more about SPACs, I learned that retail investors aren’t allowed to trade in SPACs in Hong Kong, which seems sensible to me. I get the “buyer beware” argument, but that argument in isolation stopped making sense sometime in the eighth century.

Micro funds

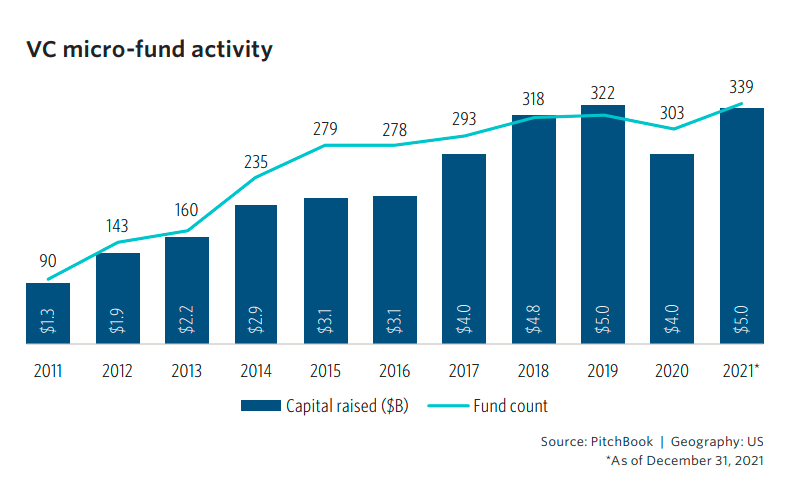

Speaking of democratization, there was another interesting Pitchbook note analyzing the growth of micro VC funds. Interestingly, over half of these micro funds are by first-time VCs.

This seems to be a general trend across the world, including India. It also seems like everybody wants to make early-stage investments:

It would not be proper to discuss the rise of micro-funds without discussing the rise in US market seed deals. Today, large multi-stage funds are propagating seed more often than ever before. Andreessen Horowitz raised a $400.0 million fund for seed; Greylock Partners allocated $500.0 million out of its billions of dollars in dry powder for seed deals, offering up to $20 million for each financing. Additionally, many nontraditional institutions have invested in seed deals. These larger firms’ participation in seed is more the exception than the rule. For micro-funds, on the other hand, seed is a core investment stage.

Pitchbook

The great rinky-dinkification of early-stage investing.

Theoretically, this means that as the bigger funds get bigger, it’s probably harder and harder for some founders to get their attention. This means these small nano and micro-funds can fill that space. On the other hand:

Over the past few years as deal sizes and valuations have increased steadily. The seed deal value growth from $1.0 million to $2.9 million over the past seven years will hurt smaller funds relatively more than larger, multi-stage funds active in the same range.

I haven’t seen much data, but I can only assume that this trend of micro-funds is a net positive for the startup ecosystem. Something to keep an eye out for.

Russia

The Jain Family Institute hosted a really interesting discussion on with Nicholas Mulder and Javier Blas on the sanctions against Russia and the turmoil in global commodity markets. Nick Mulder is the author of The Economic Weapon, a book about the history of economic sanctions that I’ve been really looking forward to reading as soon as I’m done with my never-ending backlog of books 😢. Javier Blas is the co-author of The World for Sale, a book about the global commodities markets.

A few interesting points:

- Even companies that are unaffected by this crisis are self-sanctioning over fears of sanctions compliance.

- The easy and less painful sanctions have all been imposed. There are no painless options left, and now it’s a question of burden-sharing between different European countries.

- By increasing the intensity of the military campaign, Russia can actually increase commodity prices. It’s making about $1 billion a day from commodities and energy.

- Countries have more experience restricting commodity imports than cutting exports in terms of sanctions. Countries and other intermediaries have various ways of circumventing these sanctions on commodity exports.

There was also an interesting bit on the incredible stress in the commodity markets right now. It’s so bad that The European Federation of Energy Traders wrote a letter asking for government support:

“The same company which normally expects to experience daily margin cash flows related to price movements of around 50 million euro, now faces variation margin requirements of up to 500 million euro within a business day,”

Reuters

When Javier isn’t getting trolled for making statements like this, he does some brilliant writing on commodity markets.

Here’s an excerpt from his latest piece on how oil companies are finding ways to keep the Russian energy flowing into Europe:

When is a cargo of Russian diesel not a cargo of Russian diesel? The answer is when Shell Plc, the largest European oil company, turns it into what traders refer to as a Latvian blend. The point is to market a barrel in which only 49.99% comes from Russia; in Shell’s eyes, as long as the other 50.01 percent is sourced elsewhere, the oil cargo isn’t technically of Russian origin.

Javier Blas, Bloomberg

The new normal in Russia. A really good thread on how the Russian economy seems to be adjusting to the sanctions.

Shanghai, China

China has had a zero-tolerance policy to deal with COVID-19 since day one. They’ve been ruthless and have done whatever it takes to keep the cases under check. In response to rising cases in Shanghai, one of the biggest cities, China placed the entire city with 25 million people under lockdown. The result has been a dystopian nightmare with shortages of food, basic necessities, and hospital beds.

A few threads that give a glimpse of life in Shanghai:

The other issue is that Shanghai is also a vital part of the global economy and is tightly integrated into global supply chains. Shanghai is home to some of the largest factories and also the world’s largest port, both have been seriously affected.

For the global economy, it has been a case of when it rains, it pours.

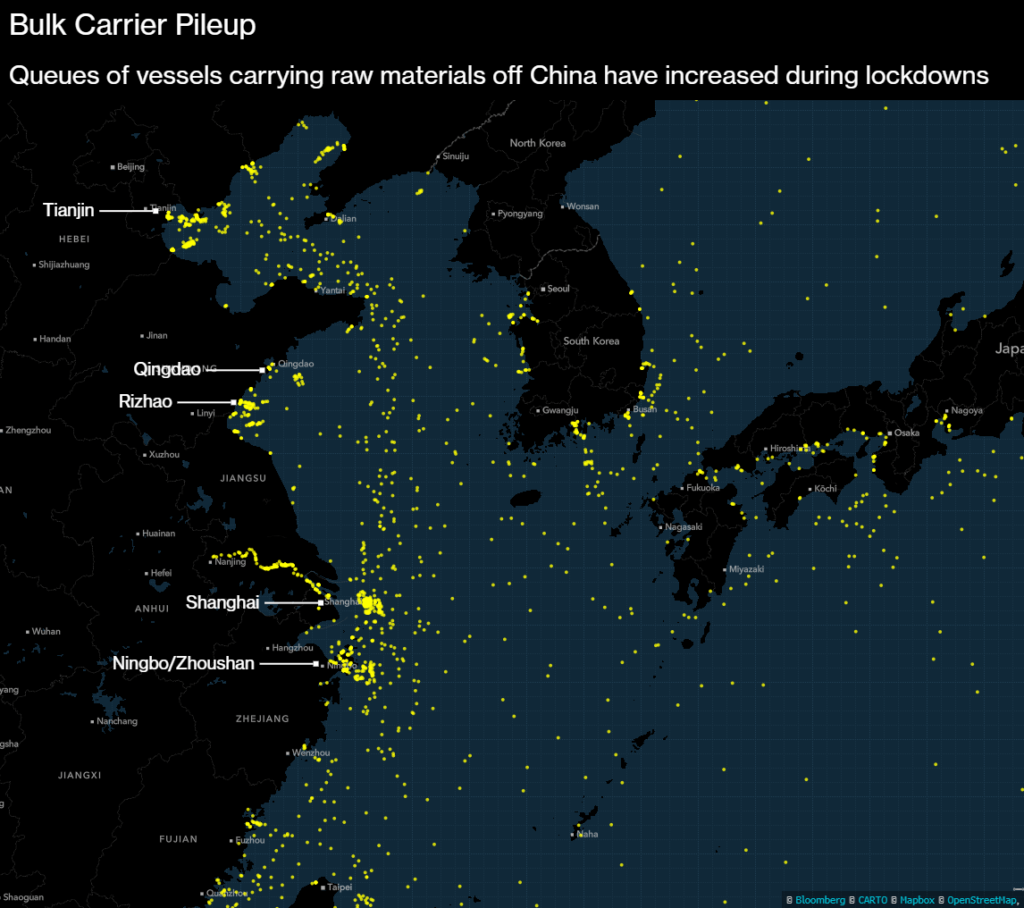

Shanghai port is more congested than my nose in winter right now, with 477 bulk cargo ships waiting to unload. Inevitably, these delays will end up increasing inflationary pressures:

Things worth reading

In a World on Fire, Stop Burning Things

Mancur Olson at the end of history

Let Them Eat Cake: Inflation Beyond Monetary Policy

How High Energy Prices Emboldened Putin

Development Economics Goes North

The jokes that have made people laugh for thousands of years

The Ancient, Female Origins of Booze

My colleague has rounded up a bunch of other interesting reads

Watch and listen

Jim Chanos on fraud and short selling

This one was pretty interesting.

Leave a Reply